Quality Improvement

Table of Contents

Definition

What is quality improvement (QI)? Let’s look at some definitions.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention defines quality improvement as“…a continuous and ongoing effort to achieve measurable improvements in the efficiency, effectiveness, performance, accountability, outcomes, and other indicators of quality in services or processes which achieve equity and improve the health of the community.” 13

The U. S. Department of Health and Human Services defines quality improvement as“…systematic and continuous actions that lead to measurable improvement in health care services and the health status of targeted patient groups.” 15

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality defines quality improvement as“…the framework we use to systematically improve the ways care is delivered to patients.” 1

History

The most commonly used QI models - Model for Improvement, Lean, and Six Sigma - were initially developed for use in the manufacturing industry.

-

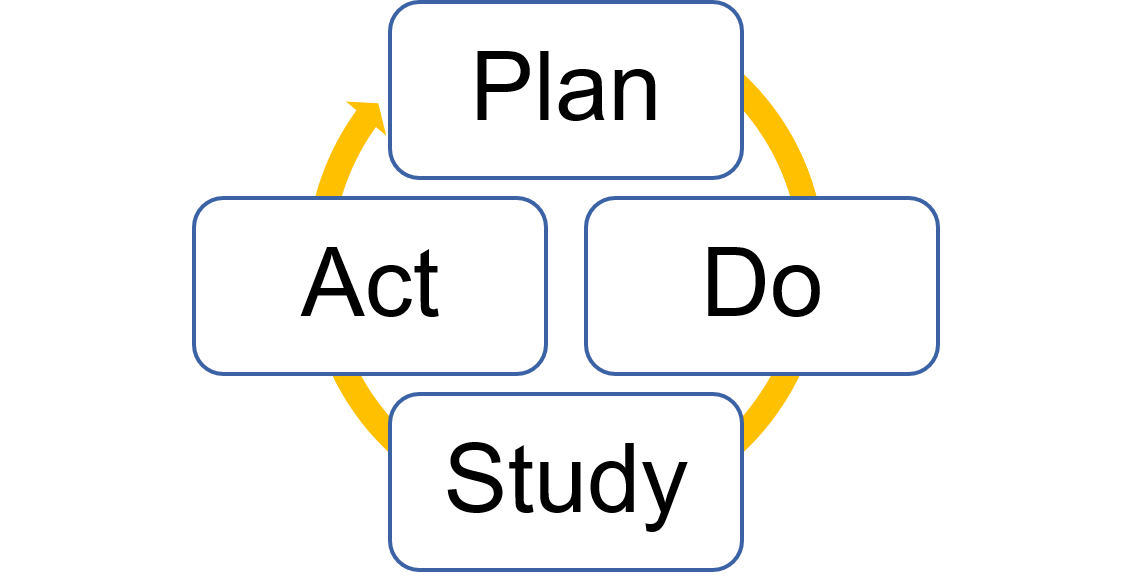

1939 (Milestone): PDSA Cycle Developed

The plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle was developed by Walter Shewhart and W. Edwards Deming, engineers at Bell Labs (now known as Nokia Bell Labs) 4, 12. The cycle is also sometimes referred to as the Shewhart Cycle or the Deming Wheel. Shewhart and Deming used the steps of the scientific method as the foundation for the cycle 4, 12. Each step of the scientific method correlates to a step in the PDSA cycle: make a hypothesis is plan, test the hypothesis is do, examine the results is study, and report the results is act. The cycle is a never ending process, continually working to improve quality. The PDSA cycle is a precursor to the Model for Improvement.

-

1948 (Milestone): Toyota Production System Developed

The Toyota Production System (TPS) was developed by Taiichi Ohno and Eiji Toyoda, engineers at Toyota Motor Company 3, 9, 14, 16. After World War II, Japan experienced critical supply shortages that prevented companies from producing large batches of inventory . The TPS streamlined the production process to eliminate any process that did not add value to the product, including overproduction and excess inventory 3, 9, 14, 16. The TPS is a precursor to Lean.

-

1986 (Milestone): Six Sigma Developed

The Six Sigma model was developed by Bill Smith, an engineer at Motorola, after the company received too many warranty claims 3, 11. The Six Sigma model standardized the manufacturing process to eliminate defects. Today, Six Sigma principles are widely adopted among Fortune 500 companies, such as General Electric, Verizon, and IBM 3, 11.

-

1988 (Milestone): The Term Lean Coined

The term "lean production" was first used in the article, Triumph of the Lean Production System, by John Krafcik 9. He used the term to describe the TPS.

-

1990 (Milestone): Lean Gained Popularity

The Machine that Changed the World by Womack et al. was published in 1990 16. It detailed the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's five year study of the car manufacturing industry . The study found Lean principles enabled Toyota to overtake the top car manufacturers of the time, such as Ford and General Motors 3, 14, 16. Because of this, Lean gained popularity and expanded to industries outside car manufacturing.

Models

When starting a QI project, it is important to use a model to help guide your project and provide feedback on your progress. As previously mentioned, the three most commonly used models are the Model for Improvement, Lean, and Six Sigma. Let’s dive a little bit deeper into each of these models.

Model for Improvement

The Model for Improvement is split into two phases. The first phase involves setting aims, establishing measures, and selecting an intervention. The second phase involves testing the intervention in real world settings using the PDSA cycle.

Phase One

During phase one, ask yourself three fundamental questions:

- What are you trying to accomplish?

- How will you know whether a change is an improvement?

- What changes can you make that will result in improvement?

Answering these questions will help you set your aims, establish your measures, and select an intervention.

Set Aims

When setting your aims, use the SMART goal format: specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound 6, 8 . SMART goals provide the clarity, focus and motivation needed to achieve your goals.

| Specific |

Goals should be straightforward and state what you want to happen. Be specific and define what you are going to do. Ask: Who needs to be involved? Where is the project going to occur? What actions will you take? |

| Measurable |

If you can't measure it, you can't manage it. Choose goals with measurable progress, and establish concrete criteria for measuring the success of your goal. Ask: What metrics will determine if you meet your goal? |

| Achievable |

Goals must be within your capacity to reach. If goals are set too far out of your reach, you will not be successful. Accomplishing goals keeps you motivated. Ask: Is the goal doable? Do you have the necessary skills and resources? |

| Relevant |

Goals should be relevant. Make sure your goal is consistent with your other goals and aligned with the goals of your company, manager, or department. Ask: Why is the project important? Does the project align with other efforts? |

| Time-bound |

Set a time frame for the goal. Putting an end point on your goal gives you a clear target to work toward. Without a time limit, there's no urgency to start taking action now. Ask: What is the start date? What is the end date? What can be accomplished within that time frame? |

Source: Goal Setting

A good way to make sure your goal is SMART is to use this formula: Verb (Measure) from X to Y by When 8 . For example, your SMART goal could be improve staff hand hygiene compliance on the medical/surgical unit from 80% to 100% within 3 months.

Establish Measures

Measurement is a critical part of testing and implementing changes. Measures inform the team if the change is effective and leading to improvement. There are four types of QI metrics: structure, process, outcome, and balance.

- Structure: measures the infrastructure, or the physical equipment and facilities. An example of a structure measure is availability of hand sanitizer pumps.

- Process: measures the activity performed. An examples of a process measure is handwashing compliance rates.

- Outcome: measures the final product or results. An example of an outcome measure is CLABSI rates.

- Balance: measures the unintentional, negative impact on a different part of the system. An example of a balance measures is staff skin breakdown.

Your team can choose to look at just one key metric, say handwashing compliance rates, or your team can choose to look at a couple metrics, say handwashing compliance rates and CLABSI rates.

Select Intervention

Before you select an intervention, you need to discover the cause of your problem. It is more effective to treat the underlying problem than the symptoms. To put it simply, if you have group A strep with a fever and sore throat, you could either stay at home or, you could visit your provider to find the root cause of your illness. Over-the-counter medications, such as acetaminophen and cough drops, will only treat the symptoms; antibiotics will treat the underlying problem. We need to do the same thing for QI projects. To do so, you will conduct a root cause analysis (RCA). You can perform an RCA using a variety of tools. Some of the more common tools are cause and effect diagrams (also known as the Fishbone diagram or Ishikawa diagram), driver diagrams, Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA), and Pareto charts.

Phase Two

During phase two, you will test your intervention using the PDSA cycle.

Source: The Improvement Guide

Plan

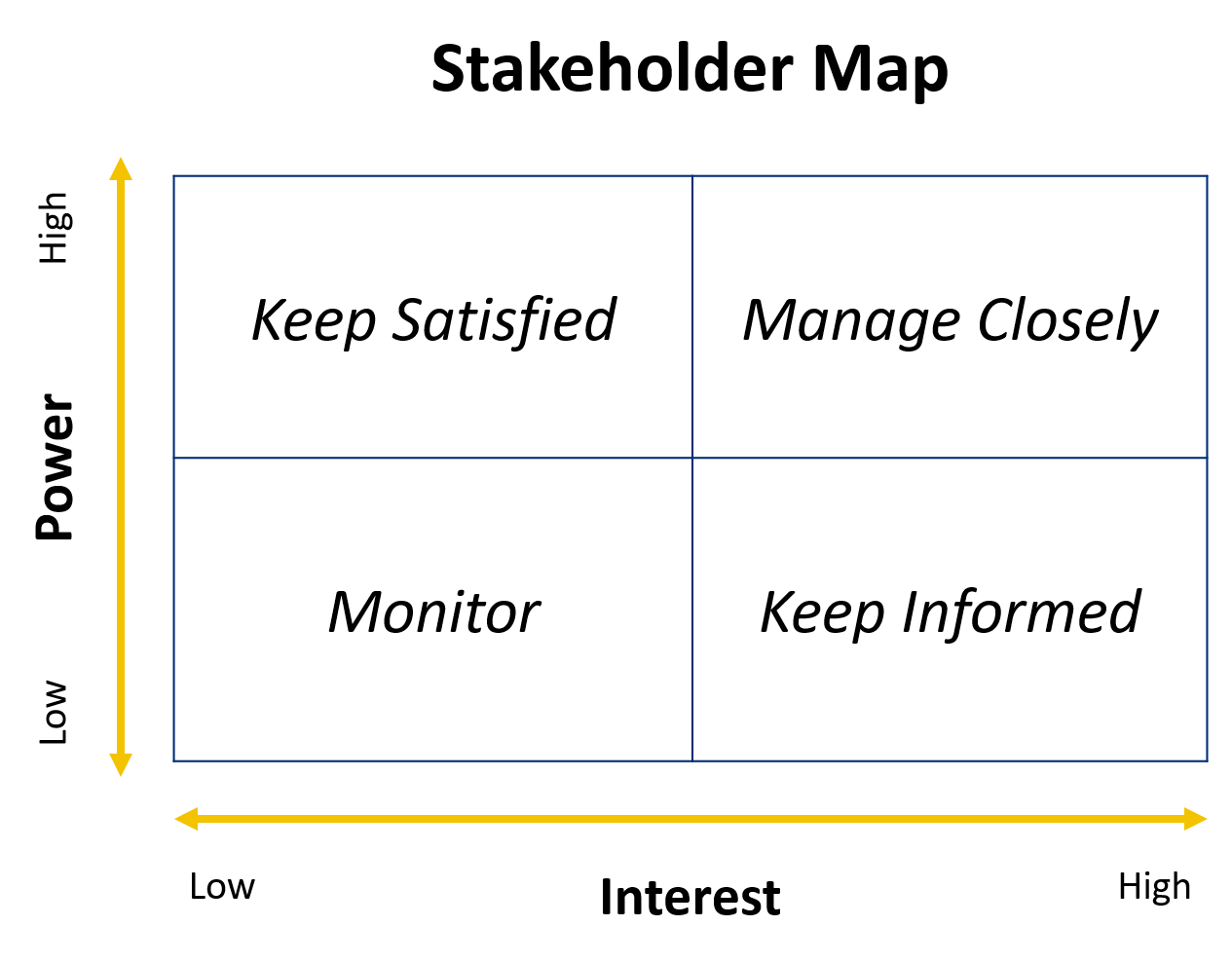

Before you implement your intervention, you need a plan. Start by identifying your stakeholders. A stakeholder is any person or group that has an interest in, or concern about your project 2. This includes management, patients and families, clinical staff, etc. Stakeholders are key to the success of your project.

Once you have your list of stakeholders, you need to determine how often to engage in each person. Some stakeholders have the power to hinder or advance your project, while others do not; some stakeholders are interested in your project, while others are not. It may be helpful to map out your stakeholders by level of power and interest 5.

Source: The Influence Agenda

Next, build your project team. Consider including some of the stakeholders you previously identified as part of your project team. In addition, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) recommends every team include members that represent three different kinds of expertise: system leadership, technical expertise, and day-to-day leadership 7.

- System leadership: People who represent system leadership have the authority to implement the intervention. They are also vital to obtaining key resources. This is typically someone in management, such as a unit manager.

- Technical expertise: People who represent technical expertise have firsthand knowledge of the problem, its context, and its impact. They can be providers, nurses, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, etc.

- Day-to-day leadership: People who represent day-to-day leadership are the drivers of the project. They understand all the details of the project and are responsible for managing the day-to-day operations of the project.

Once you have your team in place, decide how you are going to implement the intervention. Who is going to do what? When are they going to do it? What resources do you need? Answering these questions will help you organize your plan.

Do

Once your plan is in place, set it in motion. Implement your intervention on a small scale. Be sure to collect and document data.

Study

After implementation, study the results. Look at your data, analyze the results and compare them to your predictions. Displaying your data in a graph or chart may help you visualize patterns not seen using summary statistics alone. Some of the more common graphs and charts are control charts, histograms, run charts, and scatter diagrams.

Act

Finally, you will act on what you learned. Take a look at your results:

- Adopt: Did it work? Great! Let’s adopt this change and hardwire it into the system.

- Adapt: Not quite there? Time to adapt. Think about changes you can make to improve and start another PDSA cycle. QI is an ongoing process, and many cycles can be completed for one project.

- Abandon: Did you observe no improvement, or worse outcomes? Time to abandon the idea.

Lean

Waste, or Muda in Japanese, is any step or action in which the user does not gain any value 16. Although some waste is unavoidable, the main emphasis of Lean is to minimize waste as much as possible.

Lean defines 8 types of waste, or Muda: transportation, inventory, motion, waiting, overproduction, over processing, defects, and skills 16.

- Transport: The transport waste is defined as unnecessary movement of patients, supplies, or equipment. An example of this is moving a patient from the exam room to the lab for bloodwork.

- Inventory: The inventory waste refers to any supply in excess of what is necessary to produce services. In healthcare, this is a little tricky. Maintaining too much inventory can be costly, but running out of stock of vital supplies can cause patient harm. An example of this is purchasing blood collection tubes in excess, which then expire in the stock room.

- Motion: The motion waste is defined as unnecessary movement of employees. An example of this is a lab technician walking from room to room, searching for a missing glucometer.

- Waiting: The waiting waste refers to time lapsed without any activity. An example of this is a patient waiting to be seen by a lab technician for bloodwork, past the scheduled appointment time.

- Overproduction: The overproduction waste is defined as producing more than is needed, faster than needed, or before it’s needed. Overproduction can be difficult to identify in healthcare. It is most commonly seen as performing unnecessary procedures and tests. An example of this is ordering a complete metabolic panel (CMP) to routinely test blood glucose levels. A CMP requires more blood and is more expensive than a point-of-care blood glucose test.

- Over-processing: The over-processing waste refers to any redundant effort in production or communication that does not add value to a product or service. An example of this is ordering duplicate blood tests.

- Defect: The defect waste is defined as any activity that was not done according to standards, resulting in an error. In healthcare, defects are more severe as they can lead to injury or even death. An example of this is using the incorrect blood collection tube, which can lead to erroneous lab values and delays in care.

- Skills: The skills waste refers to underutilizing an employees skills or talent. An example of this is providers, nurses, or technicians habitually working below their level of licensure.

There are a dozens of Lean tools to help you identify and eliminate waste in processes and procedures. Some of the more common tools are A3 Report, 5S, Bottleneck Analysis, Value Stream Mappin (VSM), Jidoka, Kaizen, Kanban, and Poka-Yoke.

Six Sigma

The Six Sigma model is sometimes referred to as Zero Defects because it aims to eliminate defects and errors in processes and procedures. A six sigma process is one in which 99.99966% of all products are expected to be free of errors 11.

Six sigma has 2 major methodologies: define-measure-analyze-design-verify (DMADV) and define-measure-analyze-improve-control (DMAIC). The DMADV methodology is used when creating a new product or service from scratch. It is not used in health care. The DMAIC methodology is used to improve existing processes and procedures.

| Define |

Define the project goals. Ask: What are you trying to accomplish? Who needs to be involved? What resources and support do you need? |

| Measure |

Measure the performance of the current, unaltered process. Ask: How does the current process perform? |

| Analyze |

Analyze the process and determine the root causes of defects. Ask: What is the cause of the problem? |

| Improve |

Address the problem. Ask: What changes can you implement to solve the problem? |

| Control |

Continue to monitor the process and make regular adjustments as needed. Ask: Did your change result in an improvement? |

Source: Six Sigma Black Belt Handbook

Any of the tools previously discussed can be used not only for the Model for Improvement and Lean, but also with Six Sigma.

Note: Lean and Six Sigma are often used in tandem in healthcare, which is known as Lean Six Sigma or Lean Sigma. Though there are differences between the two models, the underlying philosophies behind Lean and Six Sigma complement each other well. Lean Six Sigma can be used to target both waste and defects in any component of health care delivery.

Additional Resources

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) is a federal agency charged with improving the safety and quality of healthcare for all Americans. AHRQ develops the knowledge, tools, and data needed to improve the healthcare system and help consumers, healthcare professionals, and policymakers make informed health decisions.

Armstrong Institute for Quality & Safety

The Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality oversees, coordinates and supports patient safety and quality efforts across Johns Hopkins Health System. The Armstrong Institute also offers a range of training opportunities, including Lean and Six Sigma certification, that are available to health care professionals everywhere.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) is a not-for-profit organization based in Boston, Massachusetts. It is a leading innovator in health and health care improvement worldwide. The IHI offers professional development programs — including conferences, seminars, and audio and web-based programs — to inform every level of the workforce, from executive leaders to point-of-care staff.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2013). Module 4. Approaches to Quality Improvement. https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/tools/pf-handbook/mod4.html.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2011). Section 2. Engaging Stakeholders in a Care Management Program. https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/settings/long-term-care/resource/hcbs/medicaidmgmt/mm2.html.

- Antony, J., Snee, R., & Hoerl, R. (2017). Lean Six Sigma: yesterday, today and tomorrow. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management.

- Best, M., & Neuhauser, D. (2006). Walter A Shewhart, 1924, and the Hawthorne factory. BMJ quality & safety, 15(2), 142-143.

- Clayton, M. (2014). The Influence Agenda: A systematic approach to aligning stakeholders in times of change. Springer.

- Doran, G. T. (1981). There's a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management's goals and objectives. Management Review, 70(11), 35–36.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (n.d.). Science of Improvement: Forming the Team. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/ScienceofImprovementFormingtheTeam.aspx

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Goal Setting: The Basics. https://intranet.insidehopkinsmedicine.org/jhhs_human_resources/successfactors/_docs/goal-setting-the-basics-workbook.pdf

- Krafcik, J. F. (1988). Triumph of the lean production system. Sloan management review, 30(1), 41-52.

- Langley, G. J., Moen, R. D., Nolan, K. M., Nolan, T. W., Norman, C. L., & Provost, L. P. (2009). The Improvement Guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance (2nd. ed.). Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- McCarty, T., Daniels, L., Bremer, M., & Gupta, P. (2005). Six Sigma Black Belt Handbook (Six SIGMA Operational Methods). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Moen, R. D., & Norman, C. L. (2010). Circling back. Quality Progress, 43(11), 22.

- Riley, W. J., Moran, J. W., Corso, L. C., Beitsch, L. M., Bialek, R., & Cofsky, A. (2010). Defining quality improvement in public health. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 16(1), 5-7.

- Samuel, D., Found, P., & Williams, S. J. (2015). How did the publication of the book The Machine That Changed The World change management thinking? Exploring 25 years of lean literature. International Journal of Operations & Production Management.

- U. S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration. (2011). Quality Improvement. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/quality/toolbox/508pdfs/qualityimprovement.pdf.

- Womack, J. P., Jones, D. T., & Roos, D. (2007). The machine that changed the world: The story of lean production--Toyota's secret weapon in the global car wars that is now revolutionizing world industry. Simon and Schuster.

- Zwarenstein, M., Goldman, J., & Reeves, S. (2009). Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice‐based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (3).

Page last reviewed March 2022

Page originally created March 2022