Infantile Hemangioma

What is an infantile hemangioma?

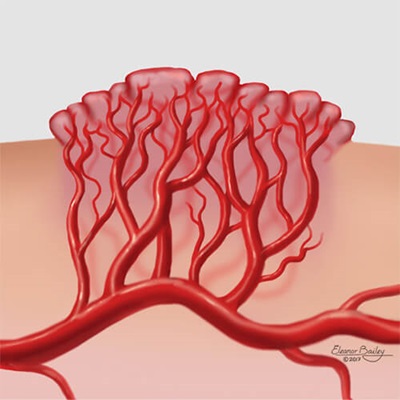

Infantile hemangiomas are made up of blood vessels that form incorrectly and multiply more than they should. These blood vessels receive signals to grow rapidly early in a baby’s life. Most infantile hemangioma will appear at birth or within the first few weeks after birth. Most infantile hemangiomas show some mark or colored patch on the skin at birth or within a few weeks after birth.

During a baby’s first five months, an infantile hemangioma will grow quickly. This time is called the proliferative phase or growth phase. For most babies, by about 3 months of age, the infantile hemangioma will be at 80 percent of its maximum size.

In most cases, they stop growing and begin to shrink by the baby’s first birthday. It will begin to flatten and appear less red. This phase, called involution, continues from late infancy to early childhood.

Most of the shrinking for an infantile hemangioma happens by the time a child is 3 1/2 to 4 years old. Nearly half of all children with an infantile hemangioma may be left with some scar tissue or extra blood vessels on the skin.

Infantile hemangioma is the most common tumor that affects babies. Infantile hemangiomas are more common in girls than boys and are more common in Caucasian children.

Babies who are born early (premature) or who have low birthweight are more likely to have an infantile hemangioma.

What are the types of infantile hemangioma?

Most hemangiomas appear on the skin surface and are bright red. These are called superficial infantile hemangiomas and are sometimes called “strawberry birthmarks.”

Some are deep under the skin and look either blue or skin-colored; these are called deep infantile hemangiomas.

When a deep and a superficial part are present, they are called mixed infantile hemangiomas.

How are infantile hemangiomas diagnosed?

Doctors can diagnose most hemangiomas by doing an exam and asking about the pregnancy and the baby’s health. Hemangiomas that are deep under the skin can sometimes be harder to diagnose. As the hemangioma grows during the proliferative phase (from birth to 1 year old), diagnosis will be easier.

Most hemangiomas do not need any special tests.

If a doctor thinks your child has an infantile hemangioma, he or she may use ultrasound to see more detail under the skin. In some cases, especially for large hemangiomas on the head and neck, the doctor may order an MRI to look at the infantile hemangioma, the brain and the blood vessels in the brain.

An MRI is a scan or picture of the inside of a patient’s body. The MRI will help the doctor see the size and location of the infantile hemangioma and check for other possible problems.

PHACE Association

Large infantile hemangiomas can sometimes be part of a syndrome called the PHACE syndrome. Each letter stands for a condition:

P – Posterior fossa (a part of the brain) malformation

H – Hemangioma

A – Abnormal arteries in the brain or big blood vessels near the heart

C – Coarctation of the aorta (A problem with the heart. The aorta is the large blood vessel that carries blood from the heart out to the body. Coarctation happens when part of the aorta is too narrow for enough blood to get through.)

E – Eye problems

Sometimes an ‘S’ is added to PHACE, which stands for sternal clefting/supraumbilical raphe, where the breastbone forms wrong or there is a scar in the skin over the chest.

Rarely, a large hemangioma — usually in the head or neck — happens along with one or more of these problems in the brain, heart, eye or blood vessels. When this happens, the baby is diagnosed with PHACE syndrome. If your doctor suspects PHACE syndrome, a special MRI, an echocardiogram (an ultrasound of the heart) and an eye exam will be done.

How are infantile hemangiomas treated?

Your child’s pediatrician, a dermatologist and sometimes a hematologist or a surgeon will care for your child’s hemangioma. Most hemangiomas do not need treatment. Those that do will be managed by a specialist. Hemangiomas will need to be monitored by you and your child’s pediatrician or a specialist.

During the first year of life, when the hemangioma is growing, doctors will want to check the hemangioma often. The number of doctor visits will depend on how big it is, where it is located on the body and whether it is causing any problems. If the infantile hemangioma starts causing problems, treatment will be recommended.

For most children, visits need to occur less often after the first birthday until school age.

Medications to Treat Infantile Hemangioma

Most hemangiomas that need medical treatment are treated with medicines called beta blockers.

Propranolol is a beta blocker (part of a class of drugs used to manage problems in the heart) that is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat infantile hemangioma. Propranolol is available as a liquid medicine taken by mouth. It has been proven to cause infantile hemangiomas to shrink.

You and your doctor should consider the risks and benefits of taking propranolol before starting treatment. A medical team with experience using propranolol to treat infantile hemangiomas will provide the best care.

Timolol is another beta blocker medicine that is related to propranolol and is available as an eye drop (though used on the hemangioma, not in the eye). It can be applied directly to the hemangioma surface on the skin. It is used to treat smaller, thin, infantile hemangiomas.

Surgical Procedures to Treat Infantile Hemangioma

Most infantile hemangiomas do not need to be treated with surgery. Surgery is less common now than in years past because of the medicines available now that are safe and effective. Hemangiomas that have noticeable scar tissue left after shrinking may need surgery. Your doctor will let you know if your child needs to see a surgeon.

Very few babies need surgery in the first year of life. When surgery is needed, it is usually done before school age to repair damage or scars caused by the infantile hemangioma. Some parents choose to wait until the child is old enough to decide whether to have surgery.

Up to half of infantile hemangiomas leave a permanent mark or scar. This can sometimes be removed or fixed with surgery. Most surgeries for hemangiomas can be done as outpatient procedures. This means that children can go home the same day they have surgery.

Our Approach to Treating Vascular Anomalies

Complications of Infantile Hemangioma

Ulceration is the most common complication of hemangiomas. An ulcer is a sore or wound that can develop on the skin over the hemangioma. Ulcerated hemangiomas can be very painful and need to be treated to help them heal.

Depending on the location of the infantile hemangioma, other complications can occur:

- Vision, when located on or around the eye

- Feeding, when located on or around the mouth

- Breathing, when located in the airway

- Diapering, when in the diaper area

- Very large infantile hemangiomas, especially when located in the liver, can cause heart failure

- Infantile hemangiomas associated with PHACE syndrome are at risk for effects on multiple body functions