Marfan syndrome

What You Need to Know

- Marfan syndrome is a congenital condition, meaning a person has it from birth.

- Physical signs sometimes present in infancy but more often show up later in childhood or adolescence.

- Marfan syndrome affects approximately 200,000 people in the United States; both men and women of any race or ethnic group may be affected.

- Both the cardiovascular and skeletal systems are affected by this condition.

- There is no cure for Marfan syndrome, but management of the associated symptoms can prolong and enhance the quality of a patient’s life.

What is Marfan syndrome?

Marfan syndrome is a rare genetic disorder of the connective tissue, affecting the skeleton, lungs, eyes, heart and blood vessels. The condition is caused by a defect in the gene that tells the body how to make fibrillin-1, often from a parent who is also affected. One quarter of cases may be the result of a spontaneous gene mutation.

Fibrillin-1 is a protein present in the body’s connective tissues. The genetic defect of fibrillin-1 leads to an increase in the production of another protein, transforming growth factor beta, or TGF-B. It is this protein’s overproduction that is responsible for the features present in a person with Marfan syndrome.

What medical problems are associated with Marfan syndrome?

Marfan syndrome primarily affects the cardiovascular and skeletal systems. People with the condition may also have vision problems; many are near-sighted, and about 50 percent suffer from dislocation of the ocular lens.

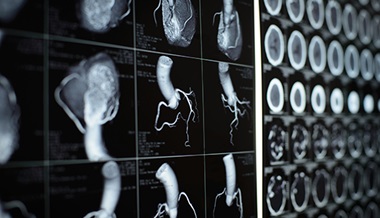

Marfan syndrome affects the cardiovascular system by making the aorta (an artery that begins at the heart and is the largest in the human body) wider and more fragile. This can lead to leakage of the aortic valve or tears (dissection) in the aortic wall, which may require surgery to repair. Additionally, the heart’s mitral valve may leak and an irregular heart rhythm may develop.

Finally, Marfan syndrome may lead to curvature of the spine, an abnormally shaped chest that sinks in or sticks out, long arms, legs and fingers, flexible joints and flat feet. Because of this, people with the condition are typically taller and thinner in stature.

What are the risk factors of Marfan syndrome?

The only known risk factor is having a parent with Marfan syndrome, as this is a condition that is most often inherited. A person with Marfan syndrome has a 50 percent chance of passing along this condition to each child. However, one out of every four people with Marfan syndrome also acquire the condition due to a spontaneous genetic mutation.

How is Marfan syndrome diagnosed?

People with Marfan syndrome exhibit different combinations of symptoms. Because symptoms of the condition overlap with other related connective tissue disorders, it is vitally important that your physicians be knowledgeable about Marfan syndrome. Tests include:

-

Echocardiogram — a sound wave picture of the heart and aorta — by a cardiologist

-

Slit-lamp examination by an ophthalmologist to check for dislocation of the ocular lens

-

Complete family history to determine other heart, skeletal or eye conditions among relatives

-

Skeletal examination by an orthopaedist

-

Genetic test for a mutation in FBN1, the fibrillin-1 gene. Fibrillin is a component of microfibrils, a group of proteins that add strength and elasticity to connective tissue. A genetic mutation is found in 90 percent to 95 percent of people with Marfan syndrome.

How is Marfan syndrome treated?

There is currently no cure for Marfan syndrome; however, careful management of the condition can improve a patient’s prognosis and lengthen the life span. The advances in medical and surgical management of children and adults with Marfan syndrome have resulted in high- quality, productive and long lives. A cardiologist will monitor the aorta and heart valves, an ophthalmologist will monitor the lens and retina of the eyes and an orthopaedist will monitor the spine, legs and feet. Physical therapy, bracing and surgery are management options. The choice of these must be individualized.

Every affected person should work closely with his or her physician(s) on their customized treatment plan. However, in general, treatment includes the following:

-

Annual echocardiogram to monitor the size and function of the heart and aorta

-

Initial eye examination with a slit-lamp to detect lens dislocation, with periodic follow-up

-

Careful monitoring of the skeletal system, especially during childhood and adolescence

-

Beta-blocker medications to lower blood pressure and reduce stress on the aorta

-

Antibiotics and other medications may be necessary prior to any dental or genitourinary procedures to reduce the risk of infection in people who experience mitral valve prolapse or who have artificial heart valves.

-

Lifestyle adaptations, such as the avoidance of strenuous exercise and contact sports, to reduce the risk of injury to the aorta

Additional Resources for Marfan Syndrome

For more information about Marfan syndrome, please visit The Marfan Foundation.