Table of Contents

- Improving Access to Pediatric Mental Health Treatment

- Feature story: Frontline Primary Care Panel Helps Fine Tune Research Studies

- Readmission Prevention Program Keeps Patients Out of the Hospital

- Feature story: From Ukraine to JHCP — Nina Steigerwald’s Journey to Become a Medical Assistant

- Holiday Album Showcases JHCP Creativity

FY23 By the Numbers

-

50+

Practices

-

920,120

Patient encounters

-

589

Providers

Reduced Clinical Hours for Primary Care Providers Improves Recruiting and Retention

Sharada Baharani, a family medicine doctor at Johns Hopkins Community Physicians–Fulton, starts her workweeks with four hours of administrative time.

Between 8 a.m. and noon on Mondays, she answers patient questions in MyChart, reviews lab reports, and works with office staff to make sure patients have the appointments and information they need.

“It’s nice to have a chunk of time to get that stuff done,” says Baharani, who joined JHCP as a full-time clinician about three years ago.

Like nearly 200 other full-time JHCP primary care providers, Baharani has had a new schedule since July, with eight hours of administrative time each week instead of four, and 32 hours for clinical care instead of 36. She still devotes four hours each Wednesday afternoon to administrative tasks, sometimes from home and sometimes staying in the office.

The change was a response to clinician burnout, and to help with hiring and retention, says Melissa Blakeman, regional medical director and medical director, patient access for JHCP. “Outstanding providers were cutting hours or leaving primary care completely,” she says.

It followed about six months of discussions that involved JHCP regional medical directors, finance leaders and trustees. “They agreed it was a critical investment,” says Ray Zollinger, JHCP’s vice president of medical affairs, one that differentiates JHCP for potential employees.

“This is a plan to ensure that we have a future workforce, and also to sustain our existing primary care physicians and advanced practice providers,” says Zollinger.

“Primary care is a particularly challenging profession in terms of the burnout in our workforce, the declining numbers of folks going into primary care because of the work-life balance and the ever-increasing demands,” he says. “As an example, a patient can send a MyChart message at 11 at night, and expect an answer within 24 hours. While that’s really wonderful care, it’s also completely unsustainable care.”

The change represents an 11% reduction in clinical time with no reduction in pay or benefits, says Zollinger. It required “substantial financial investment,” says Angie Temple, director of finance and budgeting for JHCP, who notes that it is paying off with increased retention and fewer unfilled positions.

Already, JHCP has hired 35 primary care physicians in the first six months of the 2024 fiscal year, says Zollinger, up from about 20 in previous years.

Improving Access to Pediatric Mental Health Treatment

A pilot program at JHCP Howard County embeds mental health treatment directly within primary care.

Last spring, when a 14-year-old girl went to her primary care physician (PCP) in Howard County with clear signs of depression — marks of self-harm and admitted thoughts of suicide — she was referred immediately to Holly Musgrove, a pediatric nurse practitioner and board-certified mental health specialist.

Looking back now, Musgrove says, “I hate to think what could have happened to this girl if she hadn’t had quick access to care.”

In this case, the handoff from PCP to mental health specialist within Johns Hopkins Community Physicians (JHCP) was seamless, and Musgrove quickly began cognitive behavioral therapy sessions with the teenager. But that’s hardly the norm for pediatric mental health treatment nationwide, especially in the wake of COVID-19, as rates of depression, anxiety and other conditions have exploded among young people.

PCPs — usually the first line of treatment — have found themselves unable to handle this surge, says Michael Crocetti, chief of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins Community Physicians. “We can diagnose, we can prescribe, but we simply don’t have enough bandwidth to provide the treatment that’s needed,” he says.

Referrals aren’t easy, either. The onus typically falls on the family, who must wade through lists of potential specialists — many with prolonged wait times or insurance conflicts.

With all of these issues converging, Crocetti was seeking new solutions last winter when Musgrove approached him with a promising idea. What if she, as a mental health specialist, could partner directly with the pediatric primary care team in Howard County, cutting out the need for outside referrals?

“There’s a lot of evidence that people feel more comfortable accessing mental health care if it’s offered directly in their primary care office, where they’re already established,” Musgrove says. “A lot can be said for a PCP giving that warm handoff.”

Thus began a pilot program at JHCP’s Howard County Pediatrics in February, with Musgrove serving as the go-to pediatric mental health resource for the site. Over the course of six months, she met virtually with more than 70 patients, ranging from ages 5 to 18. While medication was warranted in some severe cases, she approached most patients using cognitive behavioral therapy, helping identify and modify negative thought patterns.

In addition to making the referral process logistically easier for patients and their families, the new system increased their comfort level, Crocetti says. “A lot of times these kids are hesitant to talk to anybody else. So having someone like Holly right there, where I can say, ‘She’s part of our team, we trust her,’ it makes everything easier.”

With both patients and PCPs giving positive feedback on the pilot program, the JHCP team is now looking into how to make this model work on a larger scale across its Baltimore-area pediatric sites.

“We’re trying to figure out how to expand this,” Musgrove says, “because everybody’s already knocking at the door.”

Readmission Prevention Program Keeps Patients Out of the Hospital

Since January 2023, Medicare patients enrolled in the Maryland Primary Care Program who were hospitalized have received 30 days of extra help thanks to the Johns Hopkins Community Physicians Readmission Prevention Program (RPP).

Through the RPP, a care manager makes contact with patients — while they’re in the hospital, if possible, or as soon as they’re home — and stays in touch for 30 days after discharge. The care manager helps coordinate follow-up care and address other needs the patient may have.

“The ultimate goal is to keep patients from going back to the hospital unnecessarily because things fell through the cracks,” says Michael Albert, chief of internal medicine for Johns Hopkins Community Physicians. “There are a lot of patients who go back to the hospital for issues that could have been prevented if we provided more support when they got home from the hospital.”

“The ultimate goal is to keep patients from going back to the hospital unnecessarily because things fell through the cracks,” says Michael Albert, chief of internal medicine for Johns Hopkins Community Physicians. “There are a lot of patients who go back to the hospital for issues that could have been prevented if we provided more support when they got home from the hospital.”

Working with the Office of Population Health, JHCP streamlined the follow-up processes of care managers — who have either nursing or social work backgrounds — and nurses. These processes were sometimes siloed but often overlapped.

Some of the most common risk factors for readmission include issues taking new medications, making lifestyle changes and managing follow-up appointments.

Currently, nurses contact patients within two days of hospital discharge to schedule follow-up appointments and address post-discharge concerns. Under the RPP, a care manager can assist with this important process, including helping patients understand instructions for new medications, teaching them self-management and symptom awareness, and connecting patients to resources if they have issues with food or transportation access. Identifying changes in patient condition early so intervention can begin is crucial to keeping patients out of the emergency department.

In turn, Albert says, nurses have more time to focus on other patients, and he and his colleagues have more time to focus on patients’ medical needs during appointments since many social needs are already addressed by the RPP.

JHCP piloted the program from January to May 2023, engaging 79 patients, and it was rolled out to all JHCP primary care practices in May. In June, care managers started having daily huddles to review reports of patients who need RPP initiated and to determine who is responsible for reaching out to them. Deborah Thompson, the director of care management for the Office of Population Health, has been instrumental in honing the care management processes. She says these huddles greatly boosted RPP enrollment numbers. In June and August, 442 patients received support through the RPP.

In September, a patient with diabetes and cardiopulmonary sarcoidosis was admitted to the hospital with shortness of breath. A care manager initiated the RPP process, and identified transportation and food access issues as well as behavioral health support. The care manager referred the patient to a health behavioral specialist and a community health worker, who helped with food and transportation access. The patient has not been to the emergency department or readmitted since the RPP started.

“Patients such as this show that when we integrate central resources into our practices, it works really well,” Albert says.

Holiday Album Showcases JHCP Creativity

Does your primary care provider play the piano? Do the nurses at your physician’s office sing like Santa’s elves? Does the leader of your primary care practice belt out holiday standards on an alto saxophone?

The arts have long been a staple at Johns Hopkins Community Physicians (JHCP). From arts showcases to an online literary journal, JHCP clinicians and staff members use their creativity to promote joy and self-expression. These projects are just a few of the key inspirations for Arts at JHCP, a program created in 2022 and funded by the L. Douglas Lee and Barbara Levinson-Lee Professorship held by Steven Kravet, president of Johns Hopkins Community Physicians. The program, Kravet says, “fulfills the couple’s wishes for helping JHCP to thrive” by supporting joy and resilience across the organization, particularly at a time of high burnout because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pool of talent is deep among the physicians, nurses and staff members. During the 2022–23 holiday season, members of the JHCP team recorded The Holiday Album from Johns Hopkins Community Physicians, a playlist of both traditional and modern holiday music that’s housed on JHCP’s YouTube channel.

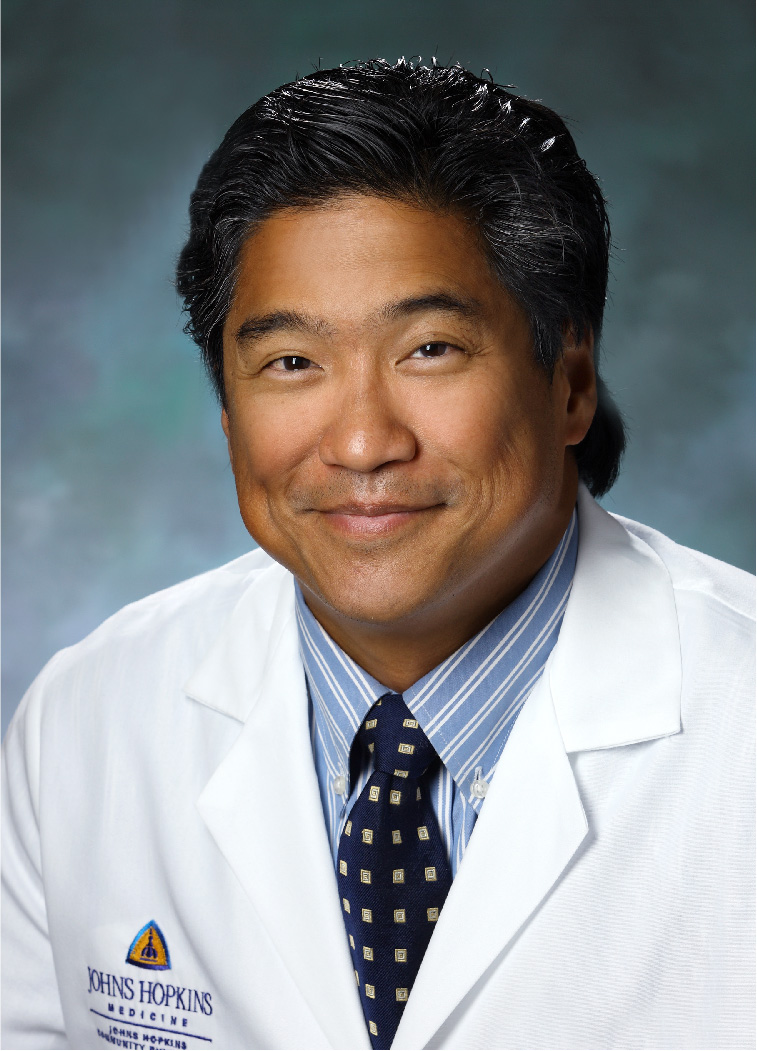

“I’ve always been struck by how much musical talent there is at Johns Hopkins and at JHCP in particular,” says Norman Dy, M.D., who arranged and produced the songs on the album.

Dy, JHCP’s medical director for direct primary care, says he and JHCP assistant director of marketing and communications Molly Jackson had the idea to produce the album. They sent out a few feelers to gauge interest across JHCP, and were surprised by the positive reaction, he says. In all, the holiday album has eight songs, ranging from traditional to modern.

Nurse practitioner Carolyn Le sings “Merry Christmas, Darling.” Catherine Davidson, a registered nurse who works in general surgery in Howard County, sings “My Favorite Things.” Clinical education nurse Kellie Renich performs “O Holy Night.” Second-year medical student Emily Larson covers Wham’s 1984 hit “Last Christmas.” Jackson and Le perform “Winter Song” together on the album.

Kravet gets into the holiday act as well, contributing with his alto saxophone on “White Christmas.”

Dy began learning the piano at age 3, and has played all his life. He considered music as a career, playing in bars in his native New Haven, Connecticut, and even at a Nordstrom department store. Despite choosing medicine as a profession, Dy stays connected to music. He’s an arranger and producer for many local musicians and groups, and has what he calls “an overdeveloped home studio” where he records and produces.

Dy says he loves helping singers find their voices.

“Most of the JHCP singers I recorded don’t consider themselves singers,” he says. “A few actually did not think they had a voice at all! But put them in the right room, with the right mic, and the right accompaniment, and they get to have a ‘Beyoncé moment’!

“I live for the moment that they open up, and it’s wonderful that I could share it with the rest of JHCP.”