In December 2019, when Judy Greengold learned of a pilot program to offer telemedicine visits, the Johns Hopkins primary care provider set a goal that seemed achievable: Perform five video visits by June 2020.

The rest is pandemic history.

Now, thousands of video visits later, the Johns Hopkins Community Physicians nurse practitioner has navigated the waters of telehealth as a clinician, patient, family member and even as an educator she is part of a telemedicine training consortium at Johns Hopkins that has developed videos for both providers and patients that are now gaining a national audience.

Greengold uses telemedicine for 70% of the 200 monthly visits she conducts with patients at her Fulton, Maryland, practice. She believes it has deepened her knowledge and commitment regarding her work, in one instance allowing her to diagnose an acute stroke. (See sidebar)

“I’ve realized even more how critical it is that primary care providers and their patients have a strong relationship,” she says. “I’ve learned how important it is to take the time to listen, to understand what you can diagnose and treat through the video, and then to move forward with confidence. That’s really been a life-changing experience for me as a clinician.”

Thousands of Johns Hopkins Medicine (JHM) clinicians have conducted roughly 1.1 million telemedicine visits since March 2020.

Before the COVID-19 lockdown, there were 50 to 70 ambulatory televisits every month, says internal medicine and pediatrics physician Brian Hasselfeld, JHM’s medical director of digital health and telemedicine. That number jumped to 94,000 in May 2020, as JHM quickly expanded its remote services to maintain vital connections to patients who otherwise would have delayed or skipped the treatment they needed. (As the pandemic has evolved and in-person care has broadly reopened, the monthly number is now about 35,000 roughly 600 times pre-pandemic levels.)

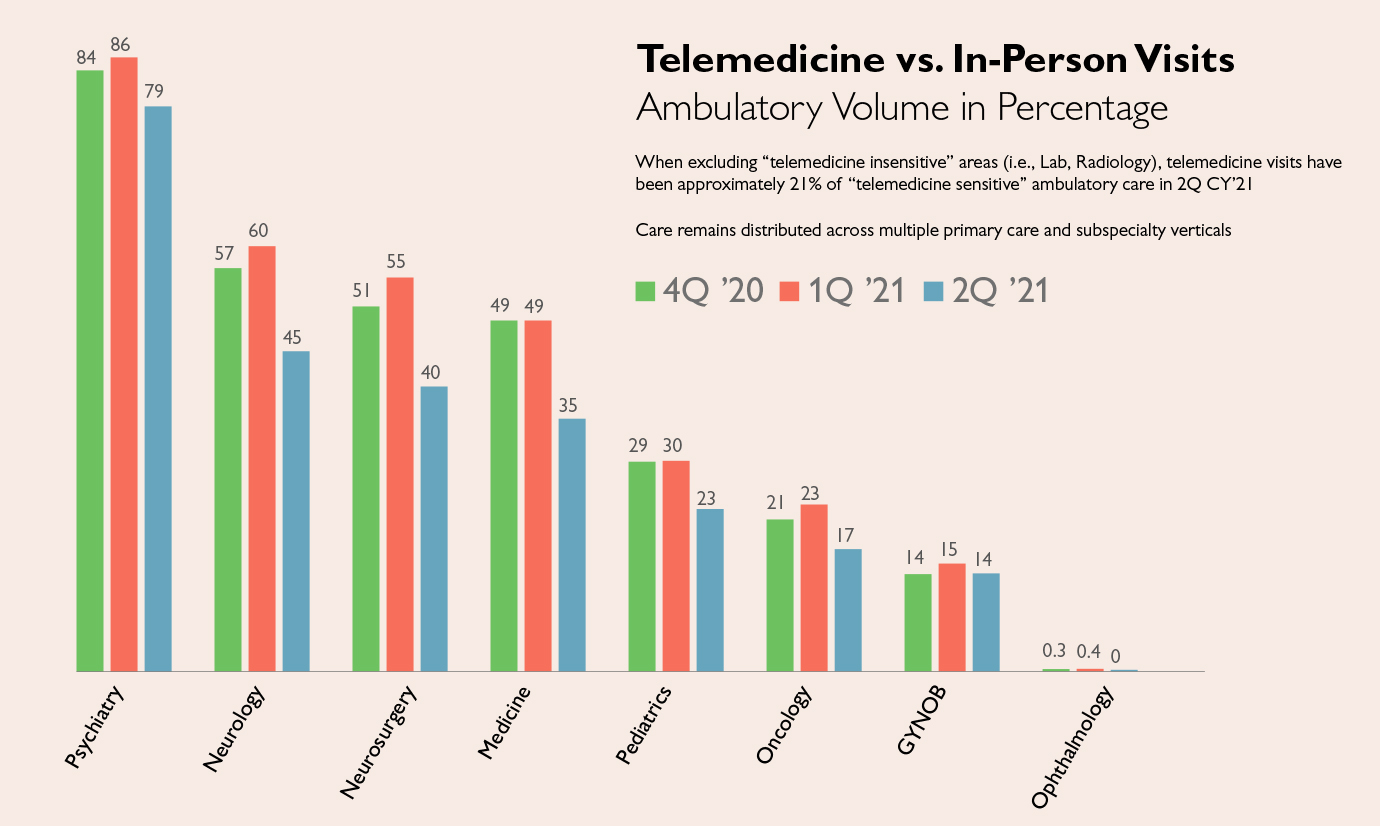

Going forward, Hasselfeld expects video visits will comprise 20% of all ambulatory patient visits, allowing patients to see providers through more convenient appointment options when clinically appropriate. Telemedicine care has been used by all departments, and Hasselfeld believes every clinical area, ranging from psychiatry and behavioral sciences to neurosurgery, will offer some level of it. Referring to telemedicine as the modern equivalent of a house call, Hasselfeld points out that the technology has led to a medical world that is more accessible, more affordable and often more personal.

“We have a unique opportunity to think about what it means to open up our doors wider,” he says.

Although not every ambulatory visit can be virtual, every specialty can offer some benefit through telemedicine, says Rebecca Canino, administrative director of the Johns Hopkins Medicine Office of Telemedicine. “If you come here for surgery, for instance, your pre and post op visits, as well as your education and post discharge follow up, can be done through telehealth, allowing you to recover safely at home.”

Benefits and Challenges of Telemedicine for Patients and Providers

As telemedicine has become a significant feature of national health care, it has also transformed Johns Hopkins Medicine. Thousands of telemedicine visits for patients of all ages have occurred in almost every specialty. Access to care has expanded to reach underserved patients in city neighborhoods and remote areas. Patients in other states have clicked on links to visit their Johns Hopkins providers. Many patients who lack computer technology have consulted with their doctors by phone. And the technology has decreased no-show rates by saving patients work and travel time while also allowing them to care for children or older parents.

Moreover, Johns Hopkins surveys show, new patients don’t generally need to wait as long to schedule their first appointment.

Johns Hopkins providers have also benefited from the technology. As they observe home environments, noting how their patients take medications and monitor blood pressure, they have gained a better understanding of specific challenges patients face in maintaining their health.

Many staff members can work from home at hours that fit in with caring for their own families. In a recent survey conducted by the Johns Hopkins telemedicine office, providers who responded said that home was their preferred place to deliver telehealth, indicating that telemedicine represents a new opportunity for work-life balance for clinicians and staff members.

Expansion of telemedicine at JHM is underway. In April, Johns Hopkins Community Physicians (JHCP) launched the JHM virtual care center, headed by nurse practitioner Mariya Rogers, which provides same day acute care when patients’ primary care providers do not have same day appointment openings. In early 2022, JHCP will open a brick and mortar primary care practice in McLean, Virginia, to accommodate its growing number of patients in that state. This new practice will be supplemented by the JHM virtual care center, offering McLean patients access to virtual urgent care after hours and during weekends.

JHM’s virtual care center serves all JHCP primary care patients.

“Part of being a value-oriented organization is to have access to whatever care is needed whenever it is needed,” says Kate Waldeisen, chief of staff for JHCP. “A virtual care center is part of a solution to enhancing access across all of our sites as they begin to see in-person visits ramp up to their pre-pandemic volumes.”

While COVID-19 has accelerated the growth of telemedicine, the public health emergency has also exposed shortcomings in the nation’s health care delivery and payment systems.

Before 2020, Medicare covered telemedicine at home only for patients in rural areas and for patients in approved health care sites. During the pandemic, however, the federal agency loosened its restrictions, allowing all of its 62 million beneficiaries to receive telemedicine services in the home, wherever they live. It also paid the same fees as for in-person visits.

“The idea that Medicare patients are older and don’t want telehealth is definitely not true,” Hasselfeld says. “We’ve had a quarter of a million of these telehealth visits during the pandemic delivered to patients with Medicare. Now we need to work at the federal level to make sure that Medicare patients can continue to access telehealth no matter where they are.”

Another priority is finding a way to allow Johns Hopkins providers licensed in Maryland to treat patients who are outside of the state at the time of their visit. Some states waived licensure requirements during the public health emergency, but those waivers have begun to expire.

Johns Hopkins is among 200 universities and associations representing higher education and health systems that are lobbying Congress to pass the Temporary Reciprocity to Ensure Access to Treatment (TREAT) Act to temporarily authorize interstate telehealth during the public health emergency. Johns Hopkins is also calling for reimbursement for visits that take place by telephone only and for management and monitoring of chronic disease at home, says Melisa Lindamood, interim vice president for the federal strategy office of JHU’s Office of Government and Community Affairs.

She says the recent rash of expirations of state emergency declarations and licensure waivers has led to a chaotic rollback in access for patients. (See the Washington Post Op-Ed article by Paul B. Rothman, dean of the medical faculty and chief executive officer, Johns Hopkins Medicine. and Kevin W. Sowers, president of the Johns Hopkins Health System and JHM’s executive vice president.)

Currently, most states require that providers be licensed in the state where their patient is located during the visit. Although such restrictions don’t keep patients from visiting a doctor’s office in another state, they do hamper their ability to use telemedicine. (A notable exception is the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Anywhere to Anywhere initiative, which allows providers who are licensed in at least one state to treat patients located in any state across the country, including while in the comfort of their home.)

This fall, most states’ pandemic-related licensure waivers expired, Lindamood says. The TREAT Act would extend those privileges.

“Patients are really contorting themselves to keep their digital appointments if their provider of choice is licensed in another state,” Lindamood says. “What has become more and more common is a ‘rest stop televisit’ — basically, folks who are very sick are forced to drive across state lines in order to sit in a Walmart parking lot and have their visit with a provider so that they’re located in the same state as the provider.”

Lindamood notes that when Virginia abruptly eliminated licensure flexibility in July, the fallout was significant for Johns Hopkins patients, especially those limited by lack of child care, transportation, time off work or financial resources to travel for care.

Providing Equal Access to Telemedicine

The race to vaccinate as many Americans as possible for COVID-19 exposed a glaring public health inequity: Those without internet access can’t easily obtain online medical information. This group includes many older, minority and immigrant patients, as well as those who require sign language and language interpreter services.

Hasselfeld and Helen Hughes, associate medical director of the telemedicine office, point out that while telemedicine has the potential to reduce health care disparities, uneven access to telemedicine introduces new forms of inequality.

For example, there are differences across patient populations in accessing telemedicine services — by video or by phone.

A recent survey by JHM’s telemedicine office shows that of the more than 1.1 million telemedicine visits across Johns Hopkins Medicine since the start of the pandemic, 18% were conducted by telephone only instead of using an audiovisual method.

According to the survey results, patients in some rural Maryland counties were heavily dependent on telemedicine visits by telephone, as were many patients in predominantly African American neighborhoods in East and West Baltimore. By contrast, predominantly white suburbs of Baltimore and Montgomery counties were far more likely to access full video visits for health care.

Hasselfeld and Hughes say clinicians should be reimbursed for the clinical care they provide, regardless of whether the method used is telephone or video.

The physicians were part of a Johns Hopkins group that helped inform members of the Maryland state legislature about keeping public health emergency waivers in place, based on an institution’s telehealth experiences. In April, Governor Larry Hogan signed the Preserve Telehealth Access Act, which removes the state’s originating site restrictions, and ensures audio-only coverage and the same reimbursement given for in person visits until June 30, 2023.

“After all it is the patient — not the health system — who knows what modality of health care communication works best for them,” Hughes says.