About 1.5 million Americans —slightly more women than men —live with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, the chronic gastrointestinal disorders collectively known as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

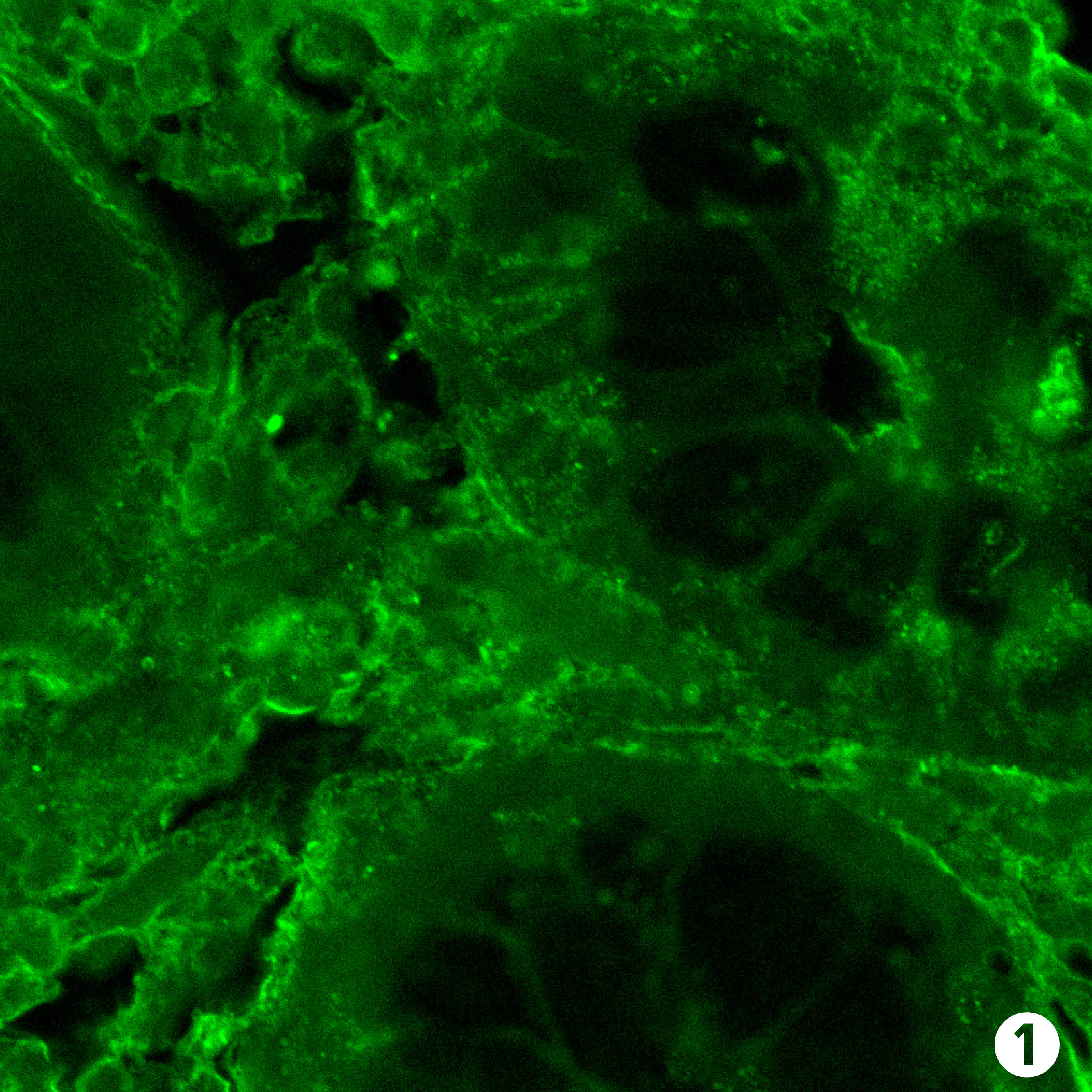

Both men and women with IBD experience painful and potentially damaging inflammation of the digestive tract. IBD has no cure; treatments focus on controlling and preventing future flare-ups with medications and treating symptoms such as abdominal pain, fever or diarrhea.

Yet IBD affects women in unique ways, says Aline Charabaty, clinical director of gastroenterology and director of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at Sibley Memorial Hospital. It can interfere with menstruation and childbirth and intensify anemia and osteoporosis, she notes.

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are not exactly the same. Crohn’s disease is characterized by inflammation in any part of the gastrointestinal tract, with symptoms that can include abdominal cramps, diarrhea, delayed growth, weight loss, fever and anemia. Ulcerative colitis affects the inner lining of the large intestine and rectum, with symptoms that often include bloody diarrhea, frequent bowel movements, abdominal and rectal pain, fever, weight loss, joint pain and rashes.

Among the most challenging complications of Crohn’s disease are fistulas — abnormal openings between the bowel and the skin (typically around the anal area) or the bowel and another organ, such as the vagina or bladder. Symptomatic fistulas are difficult to treat and often require a combination of medication and surgery.

“Our goal of care is to control the disease and inflammation so patients have a good quality of life,” says Charabaty. This includes counseling, if needed, for the social and emotional challenges posed by IBD, which is usually diagnosed when patients are between the ages of 15 and 30, she says.

“You can imagine how it can affect young people who were healthy and felt invincible, and suddenly have a chronic illness,” she says. “They have to have colonoscopies and CT scans. They typically see a doctor every six months. It takes them away from the normal life of a young person, and that can be embarrassing. So it’s understandable that the disease affects patients in terms of their body image, sexuality, academics and work, and social life — but maybe a little more for women.”

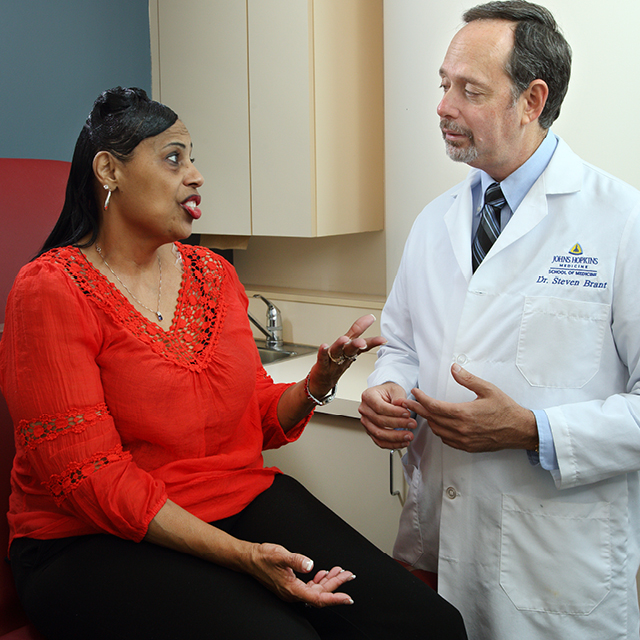

In Charabaty’s practice, she makes sure her patients receive the comprehensive treatment they need to live full and healthy lives. “It is a multidisciplinary approach,” she says, explaining that she works closely with a patient’s primary care doctor, gynecologist, psychotherapists and other specialists.

“For me, taking care of IBD patients is very rewarding,” Charabaty says. “I follow my patients for years. I see them get their health back, graduate, work, have families. It creates a very special bond between the patient and the physician.”

Here are four ways IBD poses particular concerns for women:

Menstruation: IBD, if untreated, can delay the onset of puberty and menstruation, says Charabaty. Women with IBD are also more likely to experience irregular periods and menstrual pain. IBD symptoms such as diarrhea and abdominal pain may be more severe before and during menstruation.

Pregnancy: Some women stop taking IBD medications during pregnancy because they worry that the fetus will experience side effects. But that’s actually not recommended, says Charabaty. “Most medications, including biologics, are safe during pregnancy,” she says. Stopping treatment can lead to IBD flare-ups that increase the risk of premature births or miscarriages.

Charabaty also notes that women who have perianal fistulas should not deliver vaginally because the wounds from childbirth would not heal well. She works closely with her patients’ care team in gynecology and obstetrics to ensure a safe pregnancy and delivery. In most cases, IBD does not decrease fertility in men or women. However, she says, IBD patients who need surgery to remove the last part of the colon (rectum) may experience decreased fertility.

Anemia: Women in general are at risk of anemia because of menstrual blood loss, notes Charabaty. Digestive tract bleeding associated with IBD can exacerbate the problem, as can inflammation, which blocks absorption of iron.

Osteoporosis: Women with IBD are at particular risk for osteoporosis, even before menopause, particularly if they have been malnourished or have taken prednisone for flare-ups. IBD patients typically have sensitive stomachs, often leading to poor nutrition and avoidance of calcium-rich milk products, she says. On top of that, women who don’t feel well are less likely to exercise, which can also increase their osteoporosis risk, says Charabaty. “I recommend to my patients that they eat healthy, avoid processed foods and eat fruits and vegetables in a form they can tolerate, such as cooked or grilled.”