Pediatric Epilepsy Surgery

What You Need to Know

- Surgery may be appropriate for certain forms of epilepsy that cause frequent, uncontrollable seizures in children and cannot be managed by medication or diet.

- The purposes of surgery are to target the cause of the seizures and to eliminate or lessen their severity.

- Surgical diagnostic procedures can help doctors better evaluate your child’s seizures.

When is surgery appropriate for childhood epilepsy?

If your child is experiencing frequent seizures, epilepsy surgery may be a consideration once two medication trials have failed.

Epilepsy surgery is most appropriate for stubborn, frequent seizures that start in one location in the brain (focal) due to scar tissue, tumor, cyst or another lesion that can be addressed through surgery.

Careful consideration is essential: Parents and caretakers should weigh the risks and potential advantages thoroughly with a neurosurgeon who has expertise in these procedures and how they might affect the child. The risks and benefits of surgery are weighed against the risks of persistent seizures.

Advances in neuroimaging and surgical techniques have made epilepsy surgery safer, and can give your child a chance for lasting relief. Computer-assisted neuronavigation is a commonly used technique that merges sophisticated brain imaging with computer guidance to improve the precision and safety of surgical procedures.

Surgical Diagnostic Procedures for Pediatric Epilepsy

Some of the surgical procedures related to pediatric epilepsy are diagnostic – that is, they help the doctor evaluate the cause of your child’s seizures, which can help determine the best plan for treatment.

Diagnostic Procedures

There are three surgical diagnostic procedures used to assist a physician in evaluating the cause of a child’s seizures and locating the place within the brain where the seizures are coming from.

Depth Electrodes

Depth electrodes can monitor electrical activity inside the brain. Depth electrodes are tiny, multi-contact polyurethane probes that are inserted into specified areas of the brain through small holes made in the skull and covering of the brain.

They are guided into place using three-dimensional MRI during surgery. The entry point, angle and depth are planned with computer-assisted neuronavigation to allow for precise placement of the electrode.

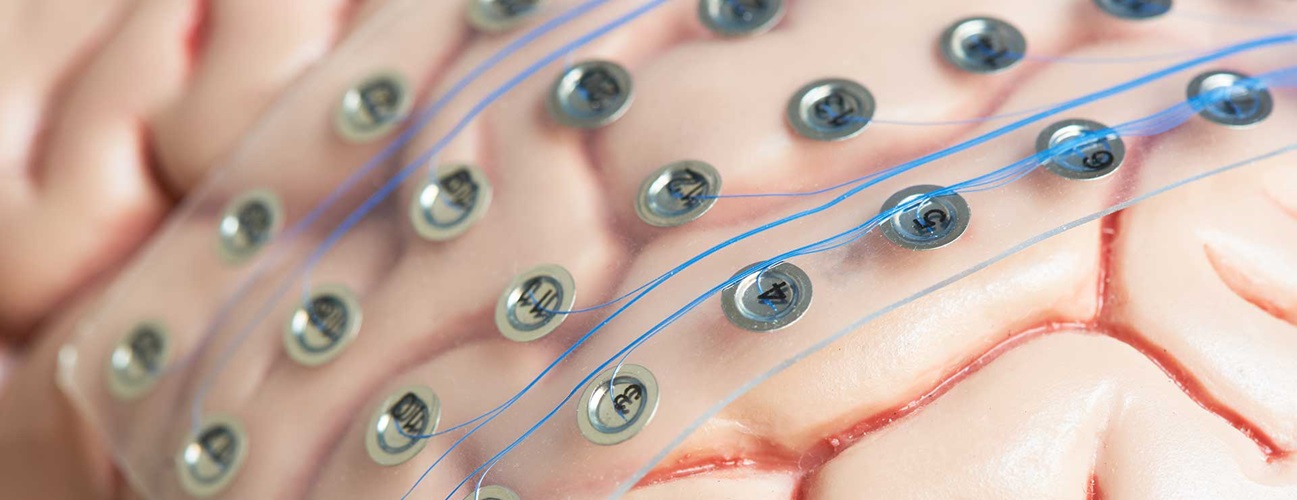

Subdural Grid Placement

Subdural grids are sheets or strips of electrodes embedded in a thin, flexible sheet of polyurethane. Within the grid are electrode discs made of a platinum alloy.

An open craniotomy (a window cut into the skull to expose part of the brain) is used to surgically place the grids over and around areas suspected to be linked to a patient’s seizures. The exact number of discs used and specific location of placement depends on the individual needs of the patient.

Subdural Strips

Subdural strips help determine in which half (hemisphere) of the brain seizures are originating. They are also used when access to a particular area of the brain may be somewhat limited.

When used alone, subdural strips are implanted through a small opening in the skull, about the size of a nickel. The surgeons use fluoroscopic guidance, and computer-assisted neuronavigation to place the strips in the optimal position.

Mapping

After the surgery to place depth electrodes, grids or strips, the child is observed for seizure activity. The child also often undergoes cortical stimulation or functional brain mapping several times to identify important functional areas that may be near the seizure focus.

The mapping involves sending a small amount of electrical current through a pair of electrodes to see what function, if any, is directly under a particular electrode while the child is playing or reading. This procedure helps the epilepsy team define the relationship between the area causing the child’s seizures and important functional areas of the brain.

Information from the electrodes helps the epilepsy team define the area of the brain that is causing the seizures (the epileptogenic zone) and plan the second surgery, which involves removing the grids and possibly addressing the seizures’ cause.

Children and Epilepsy: Everything a Family Needs to Know

Pediatric Epilepsy: Surgeries

Resection

Removal of the seizure focus is performed after an initial evaluation, or after diagnostic surgery, as described above, using a craniotomy — an open surgery to make a temporary window in the skull. The goal is to remove the source of the seizures while sparing nearby brain structures that are important for specific functions. Computer-assisted neuronavigation and intraoperative electrode recordings are used to optimize the safety and efficacy.

Ablation

Certain lesions that cause epilepsy in children can be treated with laser ablation, rather than an open craniotomy for surgical removal. Laser ablation is minimally invasive, in that it does not require the open craniotomy, and thus it often offers a faster and easier recovery. There are many of the same risks that are present with open surgery, however. Laser ablation also uses computer-assisted neuronavigation techniques to optimize safety and efficacy.

Laser Interstitial Thermal Therapy (LITT)

Patients with focal (partial) epilepsy that is resistant to medication may be candidates for laser interstitial thermal therapy. While the person is asleep under anesthesia, the surgeon drills a small hole in the skull at the back of the head and with the help of MRI guidance, navigates a laser wire to the area that is causing the seizures. After using heat to destroy the affected tissue, the surgeon removes the wire and seals the incision. Compared to a craniotomy procedure, LiTT can mean a much shorter hospital stay and recovery time.

Vagus Nerve Stimulator

The vagus nerve stimulator (VNS) is a device somewhat like a pacemaker, in that it is a device that regularly sends out electrical signals. The VNS is often used when a child has multiple or widespread sources of seizures and is not a candidate for focal epilepsy surgery.

The VNS sends intermittent electrical signals to the brain to interrupt the spread of a seizure. It is surgically placed in the upper chest below the left collarbone and connected to an electrode that is wrapped around a nerve in the neck called the vagus nerve.

The vagus nerve sends feedback signals from the body to the brain, and the VNS piggybacks on the vagus nerve to send intermittent electrical signals to the brain.

By stimulating the vagus nerve, the device can help reduce the number and severity of seizures. In fact, about a third of patients experience a 30 to 50 percent reduction in the number of seizures. Many patients also experience a marked reduction in the severity of each seizure. Around 3 percent of patients actually become seizure-free.

The device stimulates automatically and periodically throughout the day and night. Patients and caregivers can also learn to manually activate the stimulator if they notice a seizure coming on, and this can often stop the seizure from occurring.

Because the vagus nerve affects the throat, in rare instances children using a VNS may experience hoarseness or sore throat when the device delivers the electrical signal. Adjusting the strength of the stimulation can often address this issue.

VNS placement requires surgical implantation under general anesthesia, and multiple clinical appointments after implantation to turn the device on and adjust stimulation strength. The battery requires replacement every few years with a short surgical procedure.

Corpus Callosotomy

In very rare cases where a child has seizures that start independently on either side of the brain and spread, the neurosurgeon may recommend performing a corpus callosotomy. This procedure involves severing the fibers connecting the two halves (hemispheres) of the brain.

Disconnecting the two hemispheres helps stop the spread of seizures in the brain from one side to the other and may protect some children from injury caused by seizure-related falls. This procedure does not usually stop the child from having seizures and may actually increase the frequency of certain kinds of localized seizures.

After surgery, the child may experience temporary or permanent limitations of speech, movement of certain body parts or behavior alteration. It is important for parents to be informed of these risks and understand that this surgery is not performed with the hope of curing seizures, but rather with the hope of reducing their severity.

Hemispherectomy

Hemispherectomy (also known as hemidecortication or functional hemispherectomy) is the complete removal or partial removal and disconnection of almost an entire half of the brain (hemisphere).

This procedure is only performed at a limited number of hospitals. It is usually reserved for children with only the most severe epilepsy from a severely damaged or abnormal hemisphere that is causing their seizures.

Although the hemispherectomy is dramatic, experience has shown that less extensive surgery is not useful in this situation. For a very few patients, hemispherectomy has proven to be a very successful type of seizure surgery. Potential risks including hydrocephalus and infection. When successful, this surgery controls the epilepsy.

One-sided weakness, including loss of visual field on the weak side due to the damaged brain hemisphere, is likely to persist after surgery, although most patients are usually able to walk with some rehabilitation.

Pediatric Epilepsy: After Surgery

Follow-up care is extremely important in tracking the progress of your child’s recovery. Your pediatric neurosurgeon will schedule follow-up appointments to make sure your child is continuing to make progress and to assess the effect of surgery on the seizures.