Microbiome

Immunotherapy and the Microbiome

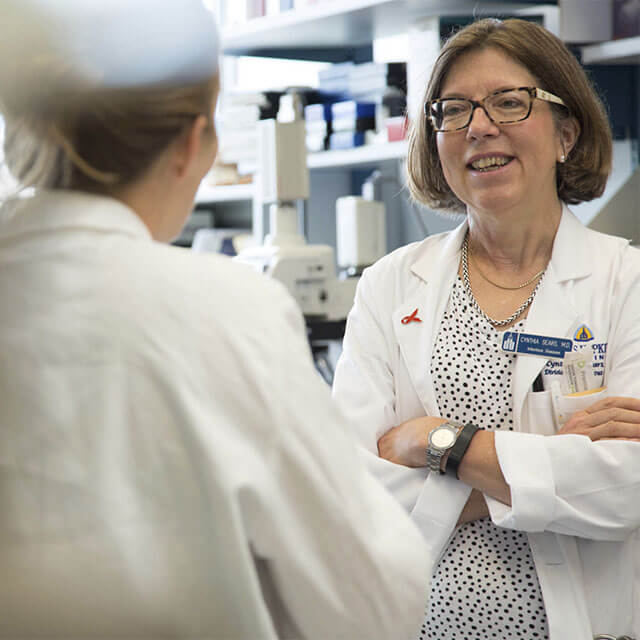

Cynthia Sears, M.D., a molecular microbiologist at The Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy is studying the microbiome, looking for ways to improve patients response in the ongoing attempt to unleash the immune system against cancer.

Cynthia Sears, M.D., leads the Microbiome Program at the Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy.

Cynthia Sears, M.D., leads the Microbiome Program at the Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy.The Microbiome Program at the Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy seeks to broaden scientific understanding of the microbiome — the community of microorganisms that reside in the human body — and find ways to apply that research to as many areas of immunotherapy as possible. It’s a brand-new program, developed and led by Cynthia Sears, M.D., whose lab studies how certain bacteria can cause inflammation in the colon and subsequently influence the development of colitis or colon cancer.

Dr. Sears and her team are working to understand how the microbiome may contribute to the genesis of an individual’s cancer development. This idea, which has been proposed in a variety of cancers, including those caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), goes back 40 years. Thanks to new genomic testing tools and enhanced sophistication of a variety of scientific methods, scientists are finally able to address the concept in more detail.

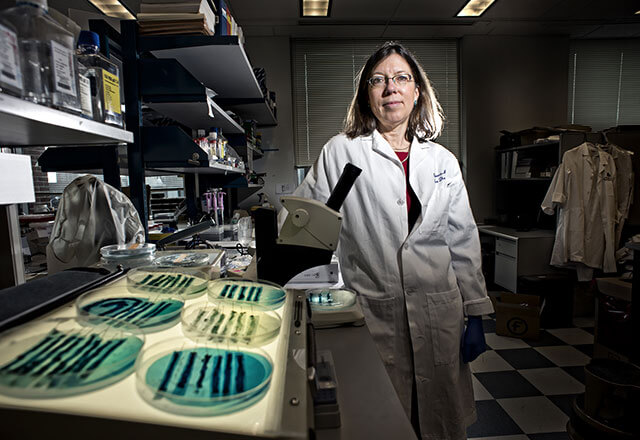

Cynthia Sears Laboratory

Principal Investigator

Cynthia Sears, M.D.

Work in the Cynthia Sears Laboratory focuses on the bacterial contributions to the development of human colon cancer and the impact of the microbiome on other cancers and the therapy of cancer. The current work involves mouse and human studies to define how enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis, pks+ Escherichia coli, Fusobacterium nucleatum, biofilms and the colonic microbiota induce chronic colonic inflammation and colon cancer. Prospective human studies of the microbiome and biofilms in screening colonoscopy are in progress as are studies to determine if and how the microbiome impacts the response of individuals with cancer to immunotherapy and other cancer therapies.

The Immune System Connection

The Microbiome Program also wants to pursue the idea that certain organisms or the composition of an individual’s microbiome can influence the body’s ability to respond to immune therapies. The idea is in early stages, with only imperfect data currently available, but Dr. Sears will be exploring it further.

Her goal is to apply any discoveries to the development of therapies, including targeted probiotics, that could improve immune response and patient outcomes.

Microbiome Program

What is the microbiome?

The microbes we carry with us — bacteria, viruses and fungi, among others — plus their associated genetic content. The human body has between 10 and 110 times more microbes than actual cells.

What does it have to do with cancer?

These organisms are essential to the health of our gut, metabolism and immune system. An abnormal or disordered microbiome has been associated with a variety of diseases, including colon cancer.

The composition of our microbiome may play into how well we respond to immunotherapy.

What are the program goals?

Understand what microbial factors may contribute to a patient’s response, or lack of response, to immunotherapy.

Develop therapies that could address these factors to improve immunotherapy outcomes.

Cynthia Sears, M.D., working with scientists in the lab.

Cynthia Sears, M.D., working with scientists in the lab.What have researchers at Johns Hopkins learned so far?

The program is new, so no results yet. But its hypotheses are based on a previous discovery by program director Cynthia Sears: that a subset of bacteria called a “biofilm” has invaded the protective mucus of some people’s colons. Patients with biofilms are up to five times more likely to develop colon cancer than those without.

What's next?

- Researchers will need to produce scientific concepts that are strong enough to support the development of next-generation therapeutics — which they admit will require a lot of patience. The team plans to design experiments to test their hypotheses after collecting and analyzing enough data.

- In 2017, the team begins gathering samples from lung and colon cancer patients who are receiving immunotherapy. Researchers will collect samples throughout the course of treatment and use a variety of experimental models to find microbial commonalities in the responders (or non-responders).

- Way down the road: the team may explore the use of fecal microbiome transplants between patients who’ve responded positively to immunotherapy to those who haven’t.