Research Story Tip: Shorter Treatment Time Needed to Prevent Hepatitis C in Kidney Transplant Recipients

09/15/2020

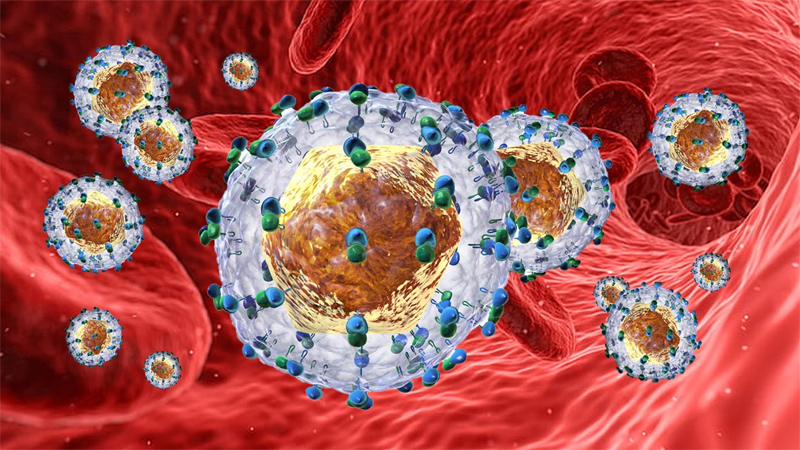

In a 2018 clinical trial, researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine demonstrated that a 12-week prophylactic course of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) — drugs that destroy the hepatitis C virus (HCV) by targeting specific steps in its life cycle — could keep HCV-negative patients virus free after they received kidneys from deceased donors who had HCV. In a new follow-up study, the researchers improved on their past success and showed that the same protection can be achieved in a third of the time without losing effectiveness or putting the recipient at greater risk of HCV infection.

The latest findings were posted online on Sept. 8, 2020, in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

According to statistics from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, nearly 100,000 Americans with kidney failure, also known as end-stage renal disease, are awaiting donor organs. Unfortunately, as reported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 9,000 of these patients drop off the waiting list each year, succumbing to death or deteriorating in health so much that transplantation is no longer possible.

Making matters worse, says the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the need for donor kidneys is rising 8% per year. However, their availability has not grown to match.

“Kidneys from deceased donors with HCV are increasingly available, yet hundreds are discarded annually because they have traditionally only been given to the small number of recipients who also had the virus,” says study senior author Niraj Desai, M.D., surgical director of the Johns Hopkins kidney and pancreas transplant program, and assistant professor of surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “Our previous trial showed it’s possible to make these donor organs acceptable for HCV-negative recipients, but the timing and duration of the DAA therapy wasn’t clear until now.”

In their clinical trial known as Renal Transplants in Hepatitis C Negative Recipients with RNA Positive Donors (REHANNA), Desai and his colleagues gave HCV-negative kidney transplant candidates a four-week course of two DAAs, glecaprevir and pibrentasvir. In the 2018 trial, 10 transplant candidates received two other DAAs, grazoprevir and elbasvir (with or without a third drug, sofosbuvir), to protect them against HCV from the donated kidneys. However, a 12-week course of treatment was needed.

Throughout most of the four-week therapy period in the new study — and more importantly, at the 12-week mark after the prophylactic treatment ended — all 10 patients were HCV free. They have all remained this way since receiving their deceased HCV-positive donor kidneys, along with showing no related adverse events such as organ rejection or liver problems.

“Although our study population was small, the trial does provide a strong proof-of-concept that transplantation of HCV-positive deceased donor kidneys to HCV-negative recipients can be successful with just four weeks of DAA prophylaxis,” says study lead author Christine Durand, M.D., associate professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “These results support adding kidneys with HCV into the overall donor pool to shorten the transplant waiting time for seriously ill patients who would not previously have had them as an option.”