Experimental Drug Development Approach Points to Better Targeted Therapies for Treatment-Resistant Leukemia

09/27/2021

New research from Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center investigators shows why some drugs in clinical trials for treating a form of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) often fail and demonstrates a way to restore their effectiveness.

The preclinical study, published in September in Blood Cancer Discovery, potentially clears a pharmacologic hurdle in developing molecularly targeted therapies for AML.

About one-third of patients with AML have a mutation in the gene FLT3. Normal FLT3 genes produce an enzyme that signals bone marrow stem cells to grow and replenish. When mutated, FLT3 causes rapid growth of leukemia cells, leading to higher rates of relapse following treatment and lower survival overall.

FLT3-mutated AML is particularly sensitive to a class of drugs called e-family tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), making them prime candidates for drug development, says first author David Young, M.D., Ph.D., who conducted the study while at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center. Dr. Young is now at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

However, these TKIs and others often fail and patients relapse. In a series of experiments with human leukemia cell lines and mice, the Kimmel Cancer Center team demonstrated that the human alpha(1)-acid glycoprotein (AGP) binds the drug, effectively preventing it from reaching its intended FLT3 mutation target and killing the cancer cells.

Donald Small, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Division of Pediatric Oncology and the Kyle Haydock Professor of Oncology at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, and colleagues treated mutant FLT3 cell lines grown in human plasma from healthy donors or standard laboratory conditions with lestaurtinib, TTT-3002 or midostaurin a drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that targets FLT3 — at various concentrations. Plasma is the clear part of blood that contains proteins and other non-cellular factors. They found that adding human plasma reduced the ability of TKI to inhibit FLT3, unlike blood components from other sources. Further testing identified human AGP as binding the three drugs and inhibiting their ability to kill leukemia cells.

To demonstrate clinical relevance of the findings, the researchers collected blood samples from adults newly diagnosed with AML and looked at the effect of their plasma on midostaurin. In the presence of high inflammation, like in newly diagnosed patients with leukemia, AGP levels are elevated. As expected, the drug lost potency in the human plasma assay from these cases.

“Midostaurin is very specific and potent, and we’ve seen about a 10% improvement in patient outcomes since the FDA approved its use in adults with AML in 2017,” says Young, “but we never got the ‘home run’ we were looking for because it’s bound by AGP.”

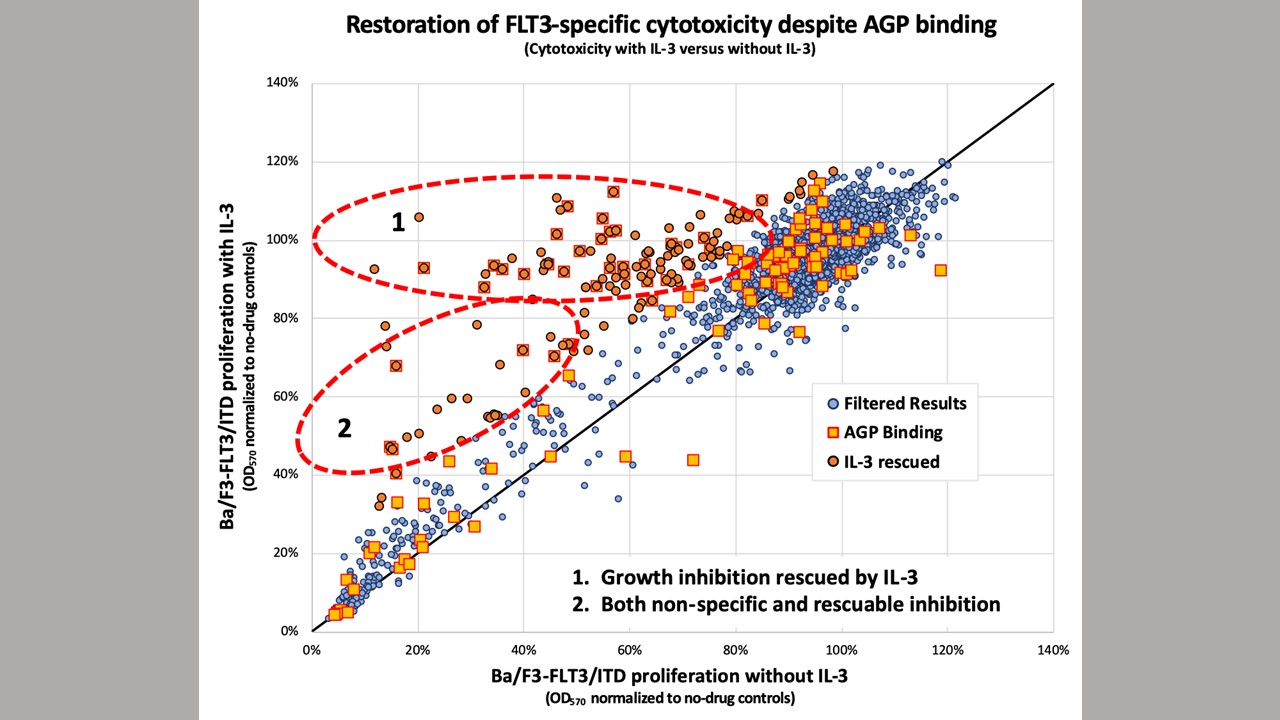

In another set of experiments, the team showed that this plasma protein inhibition could be reversed by adding an agent that also binds to AGP. Mifepristone is known to bind to AGP with an affinity comparable to or greater than that of the three drugs in the study. Researchers ran the FLT3 assay with human protein plasma, midostaurin and mifepristone. They found that mifepristone displaced the AGP-bound midostaurin, restoring its anti-FLT3 activity. Testing the concept in mice, they had similar results.

“We wanted to free up enough midostaurin to allow the drug to do its thing,” Young explains. “If we give human AGP, and give midostaurin plus mifepristone, it kills the leukemic cells. Mifepristone acts like a decoy that prevents midostaurin from binding to the glycoprotein.”

Although more testing and validation is needed, the researchers say mifepristone or other agents with similar AGP-binding properties could be tested in future clinical trials of combination TKI therapies, or developed as protein plasma “decoys” to increase the effectiveness of molecularly targeted therapies. Screening of the Johns Hopkins Drug Library — a collection of nearly 3,000 FDA-approved drugs and compounds, maintained by study co-author Jun Liu, Ph.D., co-director of the cancer chemical and structural biology program at the at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center — has offered tantalizing promises of more drugs that may function like mifepristone to restore anti-FLT3 activity and might synergize with TKI therapies in other ways.

“There may be ways to affect the pharmacology of the human body to give these old drugs new life,” Young says.

Bao Nguyen, Li Li, Tomayasu Higashimoto, Mark Levis and Jun Liu also participated in the research.

The work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01CA090668 and P30CA006973, Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation for Childhood Cancer, the Giant Food Pediatric Cancer Fund, the National Institutes of Health Fellowship for Pediatric Oncology grant (T32CA060441), the Optimist Foundation Fellowship and the Kyle Haydock Professorship in Oncology.