Hepatologist Alexandra Strauss and colleagues report in the February 2023 edition of the journal Clinical Transplantation that patients from underrepresented minority populations who require liver transplant and who live in neighborhoods of low socioeconomic status are at great risk of not receiving the procedures they need.

The team also shows that race is a key factor in patients being listed as eligible for transplant, regardless of the socioeconomic status of where they live. Patients from underrepresented populations, according to the team’s findings, have a 31% higher risk of never getting listed as candidates for transplant, as compared with those who are not from underrepresented groups.

“We wanted to find out,” says Strauss, “why some people who really needed a liver transplant never got on the list.”

Strauss and the research team conducted a retrospective cohort study of 1,377 adults referred to Johns Hopkins for liver transplant evaluation between August 2016 and December 2019. Linking deidentified data from those patients’ electronic medical records to a data set known as the Area Deprivation Index (ADI), the researchers sought to determine the role patients’ neighborhoods and socioeconomic statuses played in adding their names to the list of patients waiting for liver transplant.

“Structural racism and social determinants of health likely are contributors” to disparities in access to transplant, writes Strauss in the journal article.

Requirements of patients in need of liver transplant can be extensive. Multiple appointments and tests — as well as post-transplant follow-up care and medication compliance — pose frequent barriers to patients whose time and resources are scarce.

“Transportation, child care and other logistics may seem insignificant to people in moderate to high socioeconomic groups,” says Strauss. “But such factors are likely significant barriers to getting evaluated and listed for liver transplant.”

Strauss notes that white patients were listed for the procedure at a higher rate than Black patients, regardless of their neighborhood.

While race and ethnicity play a major role in who is listed for transplant, Strauss says that socioeconomics also cannot be discounted.

Strauss says the study is the first to use the ADI to examine disparities in liver transplant listings. Previous research relied on less granular data based on ZIP codes and census tracts. The ADI uses census block groups, which include such factors as income, education level, employment status and housing security in its determination of disadvantage for potential recipients of the procedure.

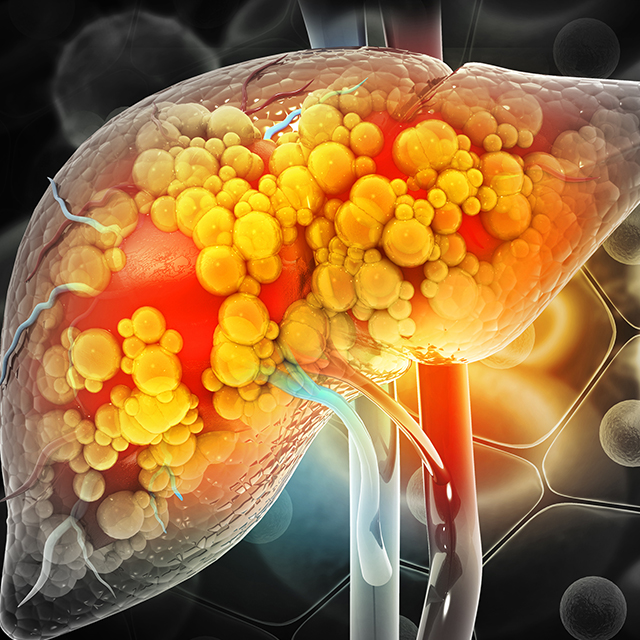

The study also showed that patients referred for transplant who live in neighborhoods with low socioeconomic status were more likely to be Black and to have Medicaid-based insurance. Those patients’ need for liver transplant stemmed mostly from hepatocellular carcinoma (the most common form of liver cancer), hepatitis C viral infection and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Referred patients from high socioeconomic neighborhoods were more likely to have alcohol-related liver disease.

Strauss says that addressing neighborhood-based disparities may also address racial and ethnic disparities.

“Our study gives us a better understanding of what we’re up against,” Strauss says. “While the roots of this problem may be in the longstanding structural racism that exists in so many of our neighborhoods, race doesn’t give us the whole picture. It’s the structural challenges that have made it hard for people from underrepresented populations to navigate the transplant process.”