One Potomac Gardens resident said she got vaccinated because she misses her family.

“I’m scared of the virus,” another said. “I don’t want to get it, and I’m at risk.”

The women were among dozens of Potomac Gardens residents who were able to get COVID-19 vaccines without leaving their senior public housing building, thanks to on-site clinics run by Johns Hopkins Medicine.

They spoke in a video created by health advocacy nonprofit Grapevine Health, which showcased testimonials from older adults and highlighted the collaboration between Johns Hopkins Medicine, the District of Columbia Housing Authority and DC Health to bring COVID-19 vaccinations to the most vulnerable populations in Washington.

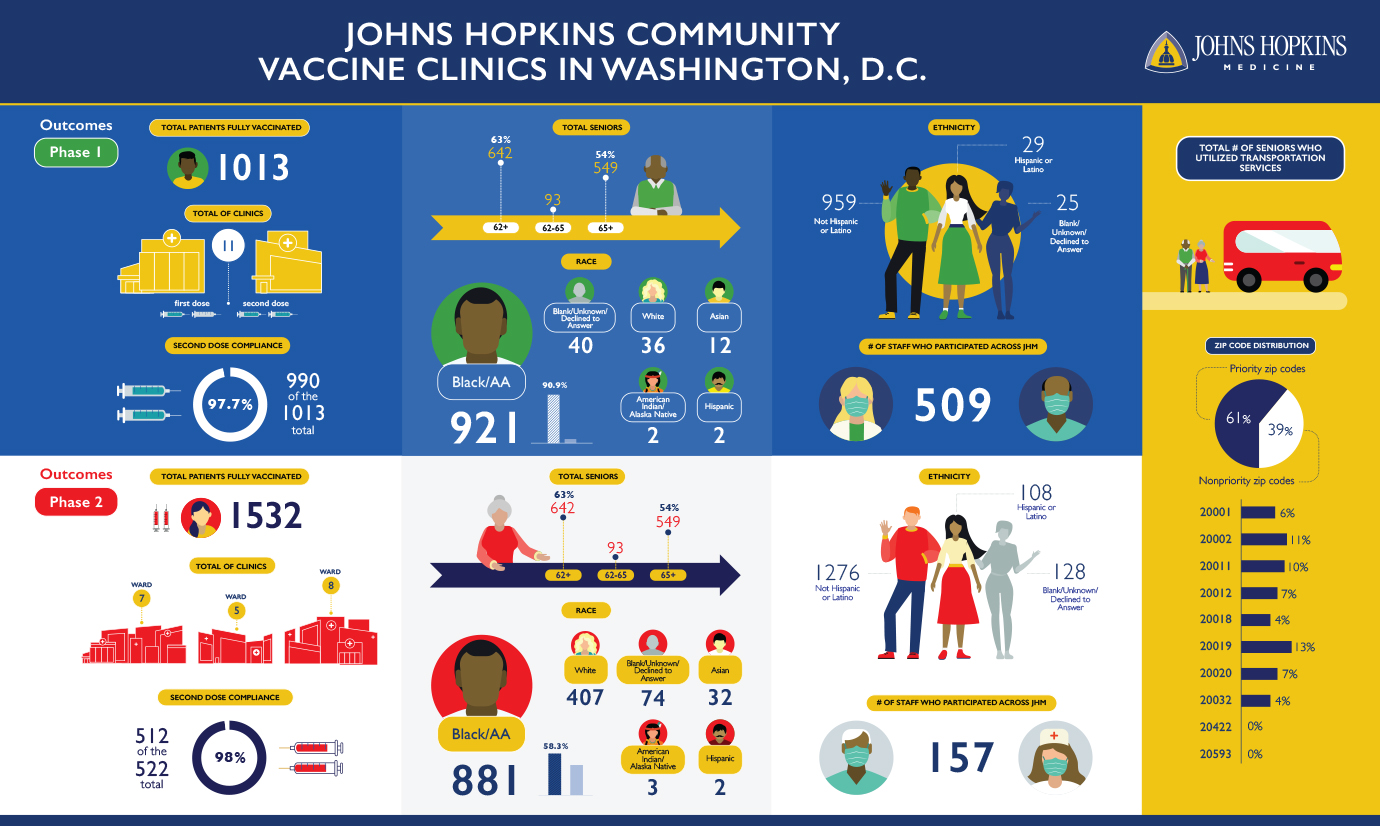

The initiative, which ran from January to April, vaccinated 1,013 people in 12 public housing complexes, plus 1,532 residents through targeted outreach to additional senior housing properties and surrounding neighborhoods in ZIP codes with low vaccination rates and high rates of COVID-19 cases and mortality.

Of those, 98% attended a follow-up clinic to get a second dose, says Marissa McKeever, director of government and community affairs for Sibley Memorial Hospital.

“I’ve been at every clinic except one,” says McKeever. “The word that I use is joy. That’s what I see on the faces of our staff and on the faces of seniors who are coming in with their canes and walkers and wheelchairs to get vaccinated. This is their golden ticket to actually being able to enjoy life. Many seniors have been so isolated throughout the pandemic.”

The Washington clinics are part of a larger vaccine equity push across Johns Hopkins Health System that targets the painful paradox at the heart of the otherwise joyful rollout of COVID-19 vaccines: The same people who are most at risk of getting seriously ill from COVID-19 are often the ones with the highest barriers to vaccination.

In Baltimore, a mobile vaccination clinic initiative, directed by Katie O’Conor, M.D., of The Johns Hopkins Hospital emergency medicine department, with an extraordinary team, is vaccinating hundreds of eligible residents a week, working with city and health department officials, as well as local faith-based organizations.

The initiative aims to improve vaccine equity by reaching people who are homebound, disabled, elderly or otherwise vulnerable. It operates five or six Baltimore clinics per week, including two a week run by Kathleen Page, M.D., co-director of Centro SOL, the Johns Hopkins-based group that promotes health equity for Latinos in Baltimore. Those clinics are at the predominantly Spanish-speaking Sacred Heart of Jesus Church in East Baltimore. Others are at public and senior housing properties.

The idea is to make it easy for people to get vaccines, even if they lack internet access to make appointments or adequate transportation to get to clinics.

“We set it up and bring everything we need for the clinic,” says Benjamin Bigelow, senior project administrator for the health system and a key organizer of the clinics in Baltimore and Washington. “If the space isn’t big enough, we might rent a tent. We’ve taken over sidewalks. It’s really amazing how much it’s meant to people when we can come to them, instead of expecting them to come to us.”

In addition to senior housing, Sibley’s community vaccination program brought the clinics to churches and recreation centers in neighborhoods particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. The Washington, D.C., Department of Parks and Recreation provided free transportation for residents in senior housing to and from the clinics, and a ride-share program funded by Sibley ensured transportation for seniors and individuals ages 18 to 64 residing in underserved neighborhoods.

Sibley’s community vaccine clinics were inspired by a January conversation between Kevin Sowers, M.S.N., R.N., president of the Johns Hopkins Health System and executive vice president of Johns Hopkins Medicine, and LaQuandra Nesbitt, M.D., M.P.H., director of DC Health.

Data reflected that vaccination rates in Washington were higher in whiter and wealthier neighborhoods. Sowers promised to help address the disparity, says McKeever.

In February and March, Sowers both visited and administered vaccines at several clinics, often staying and working for its five-hour duration.

Within two weeks of his conversation with Nesbitt, Sibley was running vaccine clinics in senior public housing properties.

“It was a necessary population to target,” says McKeever. Residents are 62 and older, and they qualify for the housing based on income and disabilities — factors that increase their risk of getting COVID-19, while also making it more difficult to track down vaccinations and travel to appointments.

Shortly after starting the program, DC Health expanded eligibility to include maintenance and security staff in the buildings that were hosting the clinic operations, says McKeever.

Each clinic lasted just a few hours, but required days of planning. A team of Johns Hopkins volunteers visited each complex ahead of time to assess the community room space and figure out how to configure the clinic while ensuring physical distancing.

Meanwhile, McKeever and Nicole McCann, vice president of provider/payor transformation, worked with Verizon to address broadband access challenges in the buildings so staff could register vaccine recipients in the Epic electronic medical record system.

DC Housing Authority distributed fliers and sent automated calls and texts to residents letting them know the clinic was coming and urging them to sign up. Housing authority officials also tapped on-site property managers, who knocked on doors throughout the clinic day, telling residents they could get vaccinated without an appointment.

On clinic days, Johns Hopkins nurses, pharmacists, community health workers and administrators arrive two hours early to set up stations for signing in, vaccination and post-dose recovery.

On average, 90 people, about half of whom were walk-ups, received vaccines during a typical 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. clinic, says McKeever.

While vaccine hesitancy is real, McKeever says most people she talks with want protection from COVID-19. Often, any concerns can be alleviated by answering questions such as how the vaccine works and how it was developed, she says.

“What I encounter is that people want to make informed decisions,” she says. “If we address vaccine access, enhance our community outreach and share information, people will get the vaccines.”