Bicuspid Aortic Valve and Congenital Aortic Stenosis in Children

Featured Expert:

Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) and congenital aortic stenosis are two types of heart defects that may be present at birth. They can occur separately or together. In some cases, bicuspid aortic valve causes another condition called aortic valve stenosis.

The aortic valve lies between the heart and the aorta, the main artery from the heart. It opens to let oxygen-rich blood pass out of the heart and into the body.

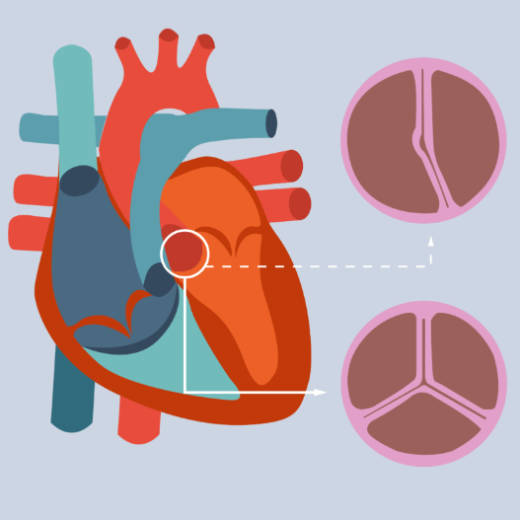

A healthy aortic valve has three flaps (called leaflets) that open to let blood through and close to prevent blood from flowing back into the heart. BAV is a condition where the valve only has two flaps. This prevents the valve from working as well as it should.

Congenital aortic stenosis develops when the aortic flaps become stiff and narrow. “When I think of a normal valve leaflet, I think of it like a sail on a sailboat. That’s how flexible it should be,” explains Hannah Fraint, MD, pediatric cardiologist at The Blalock-Taussig-Thomas Pediatric and Congenital Heart Center. “When a valve leaflet becomes stenotic, it’s more like a piece of cardboard.” Aortic stenosis causes high blood pressure in the left ventricle because the opening of the aortic valve is narrower than normal. A BAV also may not close completely, allowing blood leakage back into the heart, a condition called aortic valve regurgitation.

In the illustration above, on the top is a bicuspid valve and the bottom shows a tricuspid valve.

BAV Diagnosis

BAV is a congenital condition (present at birth). It’s often inherited, which means it can be passed down by family members. A bicuspid valve is usually diagnosed soon after birth by a pediatric cardiologist. When BAV is accompanied by another congenital heart defect, it’s often diagnosed before birth, through a routine sonogram.

The most common diagnostic test for BAV is an echocardiogram (echo). A heart echo is a type of ultrasound that uses sound waves to create pictures of the heart. An echo allows a doctor to see the structure of the heart and how blood flows through it.

If BAV is accompanied by aortic stenosis, the stenosis will be diagnosed as mild, moderate or severe. It’s common for a child who has BAV to develop aortic stenosis later in life.

Bicuspid Aortic Valve Symptoms

The most obvious symptom for all forms of heart disease in babies is poor growth due to feeding difficulties. “For a baby, feeding is exercise. Just like when someone rides a bike or walks stairs, the heart has to work harder to get blood to the body,” adds Fraint. “It’s the same thing with feeding. If a baby is having difficulty feeding, it means the heart can’t keep up with the exercise.”

While feeding, a baby with BAV may show signs of:

- Fatigue

- Labored breathing

- Sweating

Aortic Stenosis Symptoms

Older children with BAV who have also developed aortic stenosis might exhibit:

- Chest pain

- Low energy level

- Inability to keep up with other kids

- Irregular heartbeat

Aortic Stenosis Treatment

Not all children will need treatment for a bicuspid aortic valve. If the symptoms are mild and there’s no significant aortic stenosis, careful monitoring by a pediatric cardiologist may be enough.

A child with severe stenosis requires immediate care. Babies in critical condition will typically be put on medication right after birth to help facilitate blood flow from the heart to the body. They’ll stay on this medication until they’re strong enough for surgery or a minimally invasive procedure.

There are several types of intervention for aortic stenosis:

- Balloon dilation

- Ross procedure

- Valve replacement

Balloon Dilation of the Aortic Valve

Balloon dilation (balloon valvuloplasty) is the first treatment for most children with severe aortic stenosis. This is an interventional (catheter-based) procedure that is less invasive than open-heart surgery.

A pediatric cardiologist inserts a catheter into a blood vessel through a small incision in the groin. A tiny balloon on the tip of the catheter is inflated to open the narrowed valve in order to improve blood flow and lower the pressure in the left ventricle.

The procedure is done with advanced imaging for more precision. Doctors use fluoroscopy, a type of X-ray, to guide the catheter up to the aortic valve. They also perform an echocardiogram and angiograms (X-ray movies) during the procedure. Imaging provides immediate feedback about whether changes to the valve are causing improvement. Risks of balloon dilation include:

- Blood clots

- Blood vessel damage

- Infection

- Stroke

Ross Procedure

This procedure replaces the narrowed aortic valve with the child’s own pulmonary valve. Sometimes this procedure is preferable for children because the pulmonary valve will grow with the child.

Learn more about the Ross procedure for children with congenital aortic stenosis.

Aortic Valve Replacement

Aortic valve replacement is reserved for children with a severely dysfunctional aortic valve who aren't candidates for balloon dilation or a Ross procedure. An artificial valve replaces the child's own valve. There are limitations to artificial valves. This type of valve won't grow with the child, which means a second valve replacement surgery might be necessary in adulthood. A child with an artificial valve will also need to be on anticoagulants (medicine that prevents blood clots) for the rest of their life.

Lifelong Management of BAV and Aortic Stenosis

A child with a bicuspid aortic valve and aortic stenosis will need to be monitored closely for life. Monitoring may include:

- Activity restriction in some children

- Good dental care to prevent heart disease

- Frequent blood pressure checks

- Periodic evaluations with an adult congenital cardiologist

"We do a lot of counseling with parents about what to look for at home," says Fraint. "This might include watching the child's energy level and monitoring how well he or she is able to keep up with other kids. When children reach adulthood, we can help transition them to a specialist focused on adult congenital heart disease. As much as possible, we try to let kids do normal kid stuff."