About Dr. Charles Tesar

Director of Research, 1947-1974

Believing firmly that a research division of a clinical department is best headed by someone especially versed in the basic sciences and by one who will maintain his contacts with a basic science department through a joint appointment, Dr. Scott began a search for such an individual to head the Brady Research Laboratories shortly after he came to Brady in 1946. While still at the University of Chicago, Scott had several friends in the basic science departments of the medical school, one being Thomas F. Gallagher in steroid biochemistry and another being Albert Lehninger who had a joint appointment there in urology (surgery) and biochemistry.

On a visit to the University of Chicago in late 1946, Scott contacted Gallagher and learned that he had a research associate, Dr. Charles Tesar, who would finish a two-year term on June 30, 1947. Scott visited with Tesar, was immediately struck with his intelligence and warm personality, and asked Tesar if he would consider coming to Brady to direct the research laboratories. Happily for all concerned, Dr. Tesar accepted appointments as an assistant professor in both the Division of Urology and the Department of Physiological Chemistry at Hopkins effective July 1, 1947. Thus began a long association with Johns Hopkins.

Charles Tesar was born in New York City on December 31, 1906. He studied premedicine at Columbia College, obtaining an A.B. degree in 1932. Upon graduation he realized his true interests were in medical research, and therefore in the summer of 1932, he accepted an appointment as research assistant in the Department of Cancer Research at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research to work with Dr. Albert Claude. He continued his graduate studies in the evening and summer sessions as time and money were available. He received his M.A. in chemistry from Columbia University in 1940, and at that time resigned his position at the Rockefeller Institute to pursue his graduate studies full time at the School of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University. While working on his Ph.D. in physiological chemistry he was a teaching assistant in biochemistry at the Columbia School of Dentistry. In 1945 he became a research associate in the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Chicago and in 1946 received his Ph.D. from Columbia. He remained at the University of Chicago until June 1947 when he left to become the director of the Brady Research Laboratory at the request of Scott.

The laboratory was housed on the top floor of the Brady Institute and was 32 years old when Tesar arrived to take charge. It had been used at that time mainly for doing bacteriological cultures. The first order of business was to clean out the useless glassware from pre-Pyrex days and other outdated equipment. Scott had already started on this job when he had arrived in 1946. Large, metal garbage cans had been ordered and were regularly filled and emptied. Tesar said, "When I first got there in the summer of '47 we poured gallons of Mercurochrome down the sink and got rid of all the soft glass."

Scott's plan was to have every resident spend one year of the four in research, usually at the second-year level. Thus, each year there were two to three residents in the lab, often another on visiting status, and clinical staff members who were continuing research begun during their lab year. This gave them exposure to research methodology and the opportunity to do their own research with the aid and support of Tesar and Scott.

In 1965, Scott prepared a summarizing statement of Tesar's major research interests:

For the past 15 years, Dr. Tesar's activities have been directed largely in guiding novice investigators and in collaborative assistance in the research work of the division. These activities have necessarily varied widely with the interests and work of each new investigator. Although he has been active in almost all of this laboratory's problems, it was only in those projects in which he made a major contribution in their direction and assistance has his name appeared as coauthor of their publications. Some of these collaborative efforts of the recent years include: Study of prostate growth by stimulation and inhibition; isolation of the prostatic epithelial cell for respiration studies; induction of adenocarcinoma of the prostate gland; freezing of the bladder mucosa; detection and eleva- tion of bladder neck obstruction by differential pressures of bladder and posterior urethra; determination of leucine aminopeptidase in tissue and urine; and inhibition of tumor growth by glycolytic inhibition. This collaboration also includes the design and con- struction of equipment essential to the project under study but not available commercially. Some of the equipment constructed in recent years include: A liquid nitrogen boiler and spinning catheter for freezing of the bladder mucosa; a freezing-thawing machine using alcohol for the same study; and an automatic tube feeder for rats.

Early in 1959, Dr. Scott learned that Dr. Tesar had been awarded the prestigious Senior Fulbright Scholar Fellowship for the year beginning July 1, 1959. This award enabled Dr. Tesar to accept the invitation of Albert Claude, M.D., to work with him in the Laboratory of Cytology and Experimental Cancer, the Jules Bordet Institute in Brussels, Belgium. During the years 1932-1940, Tesar had worked with Claude on the fractionation and isolation of intracellular compounds by differential high-speed centrifugation. This procedure was instrumental in the purification of the Rous chicken tumor. While Tesar was on his Fulbright Fellowship, he and Claude worked on separating the cells of a mouse tumor by high-speed centrifugation. Tesar was able to establish that what was considered a single tumor initially was actually a mixture of two separate, distinct tumors. In 1974, Dr. Claude won a Nobel Prize in physiology and medicine for the initial procedure of the isolation and purification of intracellular components. Dr. Peyton Rous had shared the Nobel Prize in 1966 for his chicken sarcoma with Dr. Charles Huggins for his work on prostatic cancer.

The following letter from the Department of State to Dr. Milton S. Eisenhower, president of the Johns Hopkins University, attests to the high esteem in which Dr. Tesar was held during his year as a Fulbright scholar.

DEPARTMENT OF STATE

Washington

February 14, 1961

Dear Dr. Eisenhower: The Department would like to thank you, and Johns Hopkins University, for releasing Charles Tesar from his work in the Brady Research Laboratory, the School of Medicine, to do research at the Laboratoire de Cytologie et de Cancerologie Experimentale, Universite Libre de Bruxelles, as a grantee to Belgium under Public Law 584, the Fulbright Act, in 1959. In view of Dr. Tesar's quite outstanding contribution both to the program and to the Belgian institution, I am quoting here a part of the comments made by the binational Foundation in Belgium.

'Dr. Tesar was as fine a Fulbright scholar as his letters of recommendation said he would be. He combines rare qualities of kindness, generosity and love of humanity with great scientific ability. His contribution to the research laboratory of the Institut Bordet can scarcely be measured ... he transformed the atmosphere here by his unselfish assistance to anyone who needed his help and advice....

'Dr. and Mrs. Tesar were delightful people, excellent representatives of the United States and warmly appreciative of their Belgian experience.'

As can readily be seen, Dr. Tesar's stay in Belgium was a success both professionally and personally. The Department thoroughly appreciates the cooperation of Johns Hopkins University.

Sincerely yours,

Donald B. Cook

Director

Office of Educational Exchange

Dr. Milton S. Eisenhower

President

Johns Hopkins University

Baltimore, Maryland

In reply to the above correspondence Keith Spalding, Secretary of the Johns Hopkins University, answered:

February 17,

Dear Mr. Cook:

In the absence of the President of the University, Doctor Milton S. Eisenhower, I am writing in reply to your gracious letter of February 14th. It is a great pleasure to us and a gratification to hear praise for members of the Hopkins staff. The comments you have relayed to us about Doctor Charles Tesar are the highest kind of commendation. I shall take pleasure in sharing them with the Dean of the School of Medicine and Doctor Tesar and his associates. Thank you so much for your letter,

Sincerely yours,

Keith Spalding

Secretary of the University

Mr. Donald B. Cook

Director

Office of Educational Exchange

Department of State

Washington, D.C.

Tesar returned to the Brady Research Laboratory on July 1, 1960, and resumed his post as director. He continued to do research and construct custom equipment needed for laboratory experiments. In 1963 he was promoted to associate professor.

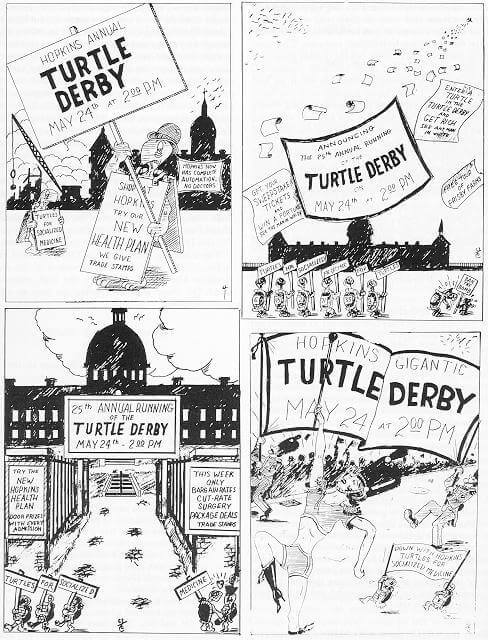

Tesar's Turtle Derby Art

Tesar's Turtle Derby ArtAlthough Tesar's education and training were in physiological chemistry, he rapidly became known in the 1950s as a talented cartoonist through his posters for the Turtle Derby. During the month of May the cartoons would appear in the main corridor of the hospital. Each day more frames appeared poking fun at the latest fads, from Elvis Presley to socialized medicine. The last week before the race, Frisby Farms, complete with stables, club house, an hurdles, would be set up in an areaway and house turtles until race time. Dr. T. (as he was affectionately called) had never had any formal art training but as schoolboy had started copying cartoons from the newspaper and soon found it was more fun to make up his own.

After this experience, Dr. T's vision of a modernized lab began to take concrete shape. During the planning and reconstruction he consulted with every member of the research staff. He took every idea into consideration, and his design met with overwhelming approval. Happily, John Lee Pratt was willing to support this renovation. By the fall of 1952 it was a reality. The animals and the operating room were moved into more spacious quarters, the walls and ceiling got plaster and paint, the cement floor was covered with green and white tile and each investigator had his own private lab/office for research. The versatile Dr. Tesar could stop being a contractor and return to research.

With the exception of the year he spent in Belgium on the Fulbright, Tesar was the Laboratory Director of the Brady Urological Institute from 1947 to 1972. He trained and supported over 50 young investigators during that period. Officially, he was granted emeritus status in 1972, but continued to carry responsibility for some projects until 1979.

Scott always had the greatest admiration for Tesar and continues to sing his praises. He also recalls with pleasure Tesar's wonderful sense of humor. The figure below is a reproduction of a picture postcard that he sent to the Scotts during his year in Belgium as a Fulbright Fellow. On the address-correspondence side of this card he had penned:

April 1, 1950

In Belgium, people say "Poisson d'Avril" (April Fish) instead of April Fool and send silly cards like this to their friends.

Wanita is off for a week in Vienna to sail down the blue Danube and waltz in the Vienna Woods while I remain here and centrifuge mouse tumor extracts.

Who is the "Le Poisson d'Avril" I wonder?

Charley T.

"Poisson d'Avril"

"Poisson d'Avril"

Among the honors he was awarded during his long and fruitful career were Research Fellow, School of Medicine, Columbia University; Senior Fulbright Scholar, The Jules Bordet Institut, Brussels, Belgium; and a Fellow of the American Association of the Advancement of Science, Washington, D.C. The societies to which he belonged were Sigma Xi, American Chemical Society, American Association for the Advancement of Science, and American Association of University Professors.

In 1982 when the Brady Research Laboratories, now under the direction of Donald Coffey, moved to their spacious new quarters in the renovated Marburg Building, a room was designed for conferences of those engaged in research. The conference room was appropriately named the Tesar Conference Room, and Charles Tesar's photographic portrait now hangs just outside its door. The inscription on the portrait reads as follows:

DR. CHARLES TESAR

A man of great character and devotion, who served as the Research Director for the laboratories of the James Buchanan Brady Urological Institute from 1947 until 1974, provided guidance and friendship to all of those who were privileged to have studies with him. His dedication to excellence serves as an example to all of us.