James Brantner had always been scrupulous about maintaining his health. He sees his primary care doctor annually, avoids sweets and developed a habit of walking 3.5 miles every other day near his home just outside Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

So when a routine colonoscopy in 2017 showed evidence of cancer, Brantner, then 76, was stunned. He’d need 12 radiation treatments, followed by surgery to reconstruct his colon. His physician recommended Johns Hopkins Hospital’s colorectal surgeon Susan Gearhart.

“The surgery [which took place last December] was quite extensive,” says Brantner, a retired planning officer for the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation. “Dr. Gearhart was very upfront with me—and compassionate.” He recalls little about his two days in the intensive care unit, but all went well during the surgery and hospital stay. And, though he’s lost 30 pounds and is not yet able to walk long distances, Brantner says he’s getting his appetite back and feels stronger every day.

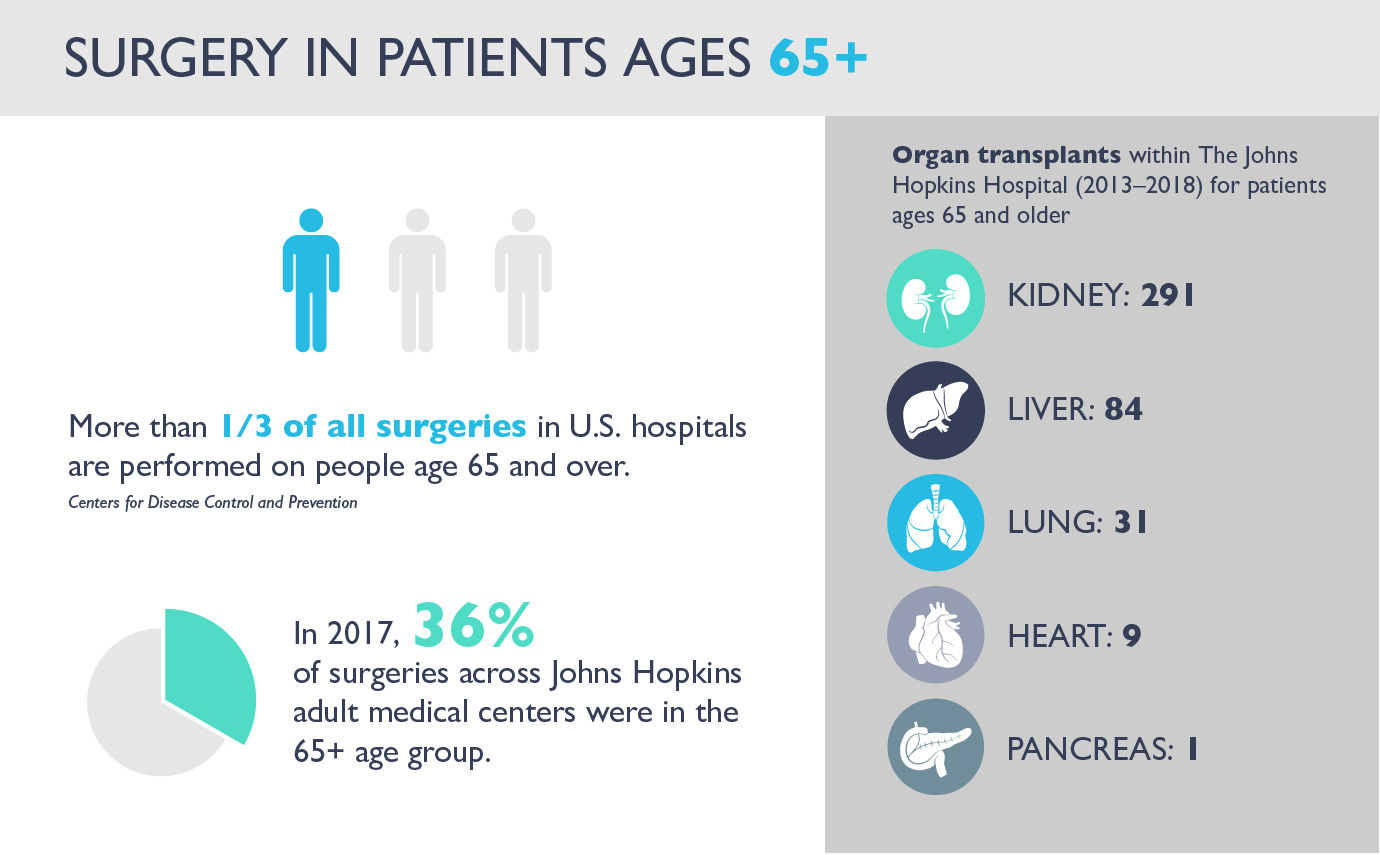

More than a third of all surgeries in U.S. hospitals—inpatient and outpatient procedures combined—are now performed on people age 65 and over, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That number, 38 percent, is expected to increase: By 2030, studies predict there will be some 84 million adults in this age group, many of whom will likely need surgery.

Last year, across all five adult Johns Hopkins medical centers, 36 percent of surgeries—48,359—took place in the 65-plus population.

Now, Johns Hopkins Bayview—a longtime hub for comprehensive health care of older adults—is poised to become a “center of excellence” in geriatric surgery. This means the American College of Surgeons will likely recognize Hopkins Bayview as offering a high concentration of expertise and resources devoted to caring for older-adult patients in need of surgery, leading to the best possible outcomes. Hopkins Bayview is one of eight hospitals expecting to merit this distinction, which also recognizes extensive research. (The others, which include community hospitals, veterans’ hospitals and academic centers, are Denver Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Kaiser Permanente Fresno, New York University Winthrop Hospital, University of Alabama, University of Connecticut, University of Rochester, and University Hospital—Rutgers’s—in Newark, New Jersey.)

Gearhart is among the leaders championing the program. Others include Perry Colvin, medical director for Peri-Operative Medicine Services; and Thomas Magnuson, Hopkins Bayview’s chairman of surgery, as well as geriatric nurse practitioners JoAnn Coleman, Jane Marks and Virginia Inez Wendel.

Shifting Perceptions of Aging

While advances in technology and medicine make it easier for people to live longer, healthier lives, no one is sure how factors such as chronological age and chronic disease affect geriatric surgical outcomes.

Consider Podge Reed. In 2011, he was 70 years old, trim and still working as chairman of the board of an oil production company. He played golf regularly and was an avid gardener. Then, during an annual physical, he learned that his lungs were impaired. He’d acknowledged having some recent shortness-of-breath episodes and was diagnosed with lung disease of unknown origin. Within a few months, Reed was placed on a transplant waiting list for a new set of lungs.

Four days after being placed on the transplant waiting list, Reed received a call from the hospital: A 41-year-old organ donor had just died, and the victim’s lungs appeared to be suitable for Reed in blood type and body size. The transplant went well, and Reed remained in the hospital for 56 days—longer than usual for most lung transplant patients because of a lung infection.

Now 77 and retired, Reed—like all transplant patients—must be vigilant about his health. He takes 18 medications daily. Since the transplant, he’s been admitted to the hospital for post-surgical infections, and he requires regular outpatient care. But that doesn’t stop him from serving in leadership roles on many patient-centered advisory committees at The Johns Hopkins Hospital. At home, in Clarksville, Maryland, he relishes spending time with his wife and their three grandchildren.

Reed says he appreciates the transplant team’s honesty, “for telling me at the outset that they were not giving me a cure but hoped the transplant could give me a longer life than currently projected.”

Since 2013, 30 other patients in that age bracket have received lung transplants. “We feel very strongly that healthy older adults should receive organ transplants and be considered as organ donors,” says transplant surgeon Dorry Segev, who is the Department of Surgery’s associate vice chair for research.

Assessing Cognition, Frailty and Function

With each passing year after age 65, older adults are increasingly vulnerable to complications and readmission after surgery, says geriatrician John Burton.

Many have multiple chronic conditions, including diabetes, high blood pressure and arthritis, and may have depression or dementia. Some take lots of medicines that cause side effects. After surgery, elderly people have more difficulty maintaining homeostasis, a physiological state of equilibrium, and suffer more readily than young patients from hypothermia, hypoglycemia and anemia. Additionally, they’re more likely to fall.

An octogenarian himself, Burton says successful surgical outcomes for older patients require meticulous planning, pre- and postoperatively. He and his colleagues assess patients by testing for frailty, cognitive lapses, depression, shortness of breath, and poor muscle tone and balance. Specially trained geriatric nurses, pharmacists, physical therapists and social workers also play a crucial role.

Ultimately, says Burton, surgical success requires strong communication between the surgical team and family members. They need to discuss strategies to prevent delirium, a common postsurgical complication, and how to manage medications. The care team also schedules “prehab”—working with a physical therapist and others to strengthen muscles before the surgery.

These efforts have already taken root through the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery program, a coordinated approach to help reduce delirium, infections and other harm in surgical patients.

Delirium and Fuzzy Thinking

In the weeks following surgery, some patients experience a period of prolonged fuzzy thinking known as postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Studies suggest that about one in 10 older adults develops the condition during the first three months after surgery, says anesthesiologist and critical care medicine physician Charles Hugh Brown IV. The highest risk factors, he says, are cognitive problems before surgery, procedure invasiveness, and the likelihood of much blood loss.

“Most older adults can go through surgery well,” says Brown, “But no one takes the decision lightly. We need to understand who’s really at high risk (for postoperative cognitive dysfunction) and what we can do to modify factors.” These include performing a less invasive surgery, adjusting medications, encouraging mobility after surgery, and making sure patients with hearing aids and glasses use them.

Extending Hope

The knowledge base of caring for older-adult patients who need or want surgery continues to grow, says geriatrician Michele Bellantoni. And, using best practices based on national criteria for geriatric surgical care, she and her colleagues are teaching the next generation of medical residents the particulars of elder care through a rotation on the geriatric medicine service.

A growing area of focus for the 65-plus population is blood cancers. Last year, for example, Podge Reed’s 76-year-old wife, Natalie, received bone marrow from their oldest granddaughter to help treat her acute myeloid leukemia, diagnosed in April 2017. The transplant, performed four months later, at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, proved successful. Because blood disorders are on the rise in the elderly population—as are bone marrow transplants—the cancer center expects to perform more of these life-extending procedures.

Five months after James Brantner’s colon surgery, he reports that he’s enjoying more of his favorite foods and that his stamina has increased.

The last time he saw Gearhart, Brantner mentioned he was still worried about his health. After examining him and learning about his progress, she reassured him: “You know what? You’re going to be all right.”

“I had to agree,” Brantner says. “You can’t go through life thinking about this all the time. I have a wife, two sons and two grandchildren, and I intend to make the most of my time.”

See a video about geriatric care at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center.