In U.S. prisons and jails, women, nonbinary and transgender people who are pregnant or postpartum are not consistently provided standard medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), according to a 2022 study by medical anthropologist and obstetrician-gynecologist Carolyn Sufrin and her team.

“If you’re trying to address the health care needs of incarcerated people, especially incarcerated pregnant people, you can’t ignore the substance use issues,” she says. “When it comes to opioid use disorder, pregnant people have been left out. It’s really important to make sure they’re not forgotten.”

Sufrin was recently recognized in a report by the American Medical Association and Manatt Health for her work with this group of people. She was among 25 physicians, policymakers, researchers and advocates acknowledged for their innovative work in tackling the opioid epidemic. Sufrin, who leads a research group called Advocacy and Research on Reproductive Wellness of Incarcerated People, says the honor is “very gratifying.”

“The AMA has been devoting a lot of attention to the opioid epidemic, and some attention to incarcerated populations, but the issue of pregnant incarcerated people with opioid use disorder has not really crossed its radar,” she says. “It was very gratifying for them to take an interest and recognize the critical issues that this population faces.”

The report, The Fight to End the Nation’s Overdose Epidemic and Restore Compassionate Care: Profiles in Leadership, features people whose work illustrates six areas the AMA and Manatt outlined in a 2022 toolkit that recommended evidence-based treatment and solutions to tackle the opioid epidemic (see sidebar).

Sufrin received her medical degree from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in 2003. She subsequently worked as an obstetrician-gynecologist at the San Francisco County Jail, where she learned about the complex health care needs of pregnant people who are incarcerated by caring for them. Those experiences, from 2007 through 2013, inspired her 2017 book, Jailcare: Finding the Safety Net for Women Behind Bars, as well as her research endeavors.

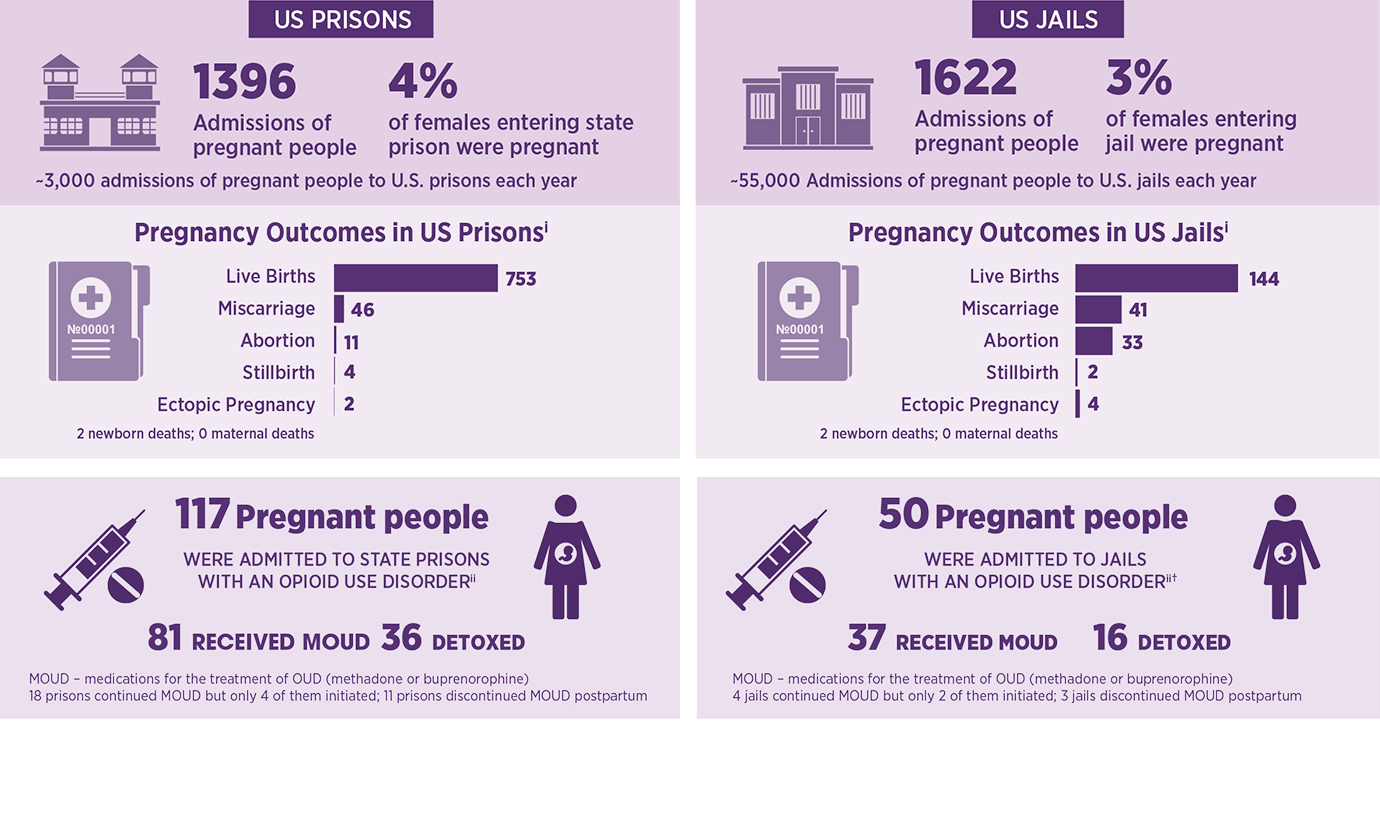

Sufrin’s research also includes a 2019 study that offered a first-of-its-kind systematic look at pregnancy frequency and outcomes among women imprisoned in the U.S. — data that U.S. federal agencies and state prison systems have not historically tracked. Known as the PIPS study (Pregnancy in Prison Statistics), it reports that among 3,018 pregnant women admitted to participating U.S. state and federal prisons and jails in a one-year period, 167 of them were admitted with an opioid use disorder. Researchers found that 118 received MOUD methadone or buprenorphine, and 52 may have been administered other medications to ease withdrawal symptoms.

Based on that research, Sufrin estimates that of the 58,000 pregnant people admitted to U.S. prisons and jails each year, 13%, or 7,700, have opioid use disorder. And while jails and prisons are obligated to provide health care for people who are imprisoned, there are few standards governing that care, and no mandatory standards of care for pregnant people.

Methadone and buprenorphine — standard medications to treat opioid use disorder — are safe and effective treatments for pregnant people, Sufrin says. These well-studied medications do not cause birth defects or fetal anomalies. Various studies show that pregnant people with opioid use disorder who take these medications are more likely to engage in prenatal care and behavioral counseling; are less likely to relapse or overdose; have lower rates of acquiring new infections, such as HIV or hepatitis; and have lower rates of preterm births and stillbirths.

While there’s still more work to be done in the treatment of imprisoned pregnant people with substance use disorder, Sufrin says, she has seen progress in her time working with this population. In Maryland, a new law taking effect this year will require all jails and prisons to provide MOUD. She says more general resources are available for the health care needs of women and female-presenting people in the carceral system, but availability and implementation vary greatly.

To that end, she and her team are creating a website, supported by a grant from the American Association of Obstetrician and Gynecologists Foundation, that will also help jails and prisons implement best practices in caring for incarcerated pregnant people with opioid use disorder. The goal is for institutions of any size to find it useful.

“What Rikers Island in New York City can do is much different than what a small jail in Arkansas is able to, but both jails need to be able to provide treatment,” she says. “We’re hoping to build this as a practical tool that can be implemented to directly impact the care that someone receives at any institution.”