Veterinarian Rebecca Krimins is at the cutting edge of medical research at Johns Hopkins, and her work has the potential to benefit millions of patients — human and animal. Krimins is pioneering research into radiopharmaceutical therapy in veterinary patients. While she does not directly treat humans, her work is advancing radiation treatments for pets that may someday benefit people. Krimins is an assistant professor in the Department of Radiology and Radiological Science and founder/director of the Veterinary Clinical Trials Network at The Johns Hopkins University, where she collaborates with other experts to bring newly developed therapeutic and diagnostic tools to veterinary patients. “The diseases I treat and therapies that I use are translational to humans,” Krimins explained. “I look at therapies and collaborate with specialists to share findings in pets that may benefit people.” In recent years, Krimins has focused much of her work on developing radiopharmaceutical therapies for veterinary patients.

Also known as targeted molecular radiation therapy, radionuclide therapy or radio-theranostics, the therapy involves introducing radioactive material designed to work in specific locations of the body to treat a medical condition including cancer. Radiopharmaceutical therapy has been used to treat human patients since the 1940s, and it remains a rapidly-growing field. Radiopharmaceuticals can be used for diagnostic imaging purposes as well as treatments. For example, flourine18-DCFPyL is a radiotracer that binds to prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA). In men with prostate cancer, 18F-DCFPyL PET imaging allows physicians to visualize specific locations in the body where the cancer has metastasized. Research into radiopharmaceutical therapy in veterinary patients began in the 1980s.

By the 1990s, Iodine-131 (sodium iodide) was being commonly used to treat feline hyperthyroidism. During I-131 treatment, patients must spend up to a week at the veterinarian’s office due to the potential of human exposure to radiation. This can be a major drawback of treatment for pet owners considering treatment options. Within the past two years, two new radiopharmaceuticals have been approved for therapeutic purposes in veterinary medicine: yttrium-90 (hydrogel solution) and tin-117m (colloid solution).

Krimins uses Y-90 hydrogel therapy to treat solid cutaneous malignant tumors. It can also be used inside the body following removal of an intra-cavitary malignant tumor to ensure all cancer cells are eradicated. The radioactive material is prepared and administered for each patient individually based on the type and location of the cancer and other factors. The Y-90 hydrogel is injected into the tumor at 5 millimeter spacings. Therapy is outpatient; animals can go home the same day as treatment. This newer radiopharmaceutical is not excreted, and it does not migrate or irradiate healthy tissue, Krimins noted. Post-treatment, owners are advised to limit prolonged direct contact between humans (especially children and pregnant women) and the treated tissue for several weeks following treatment to limit any potential exposure.

In her research, Krimins offers several case studies of patients treated for malignancy with Y-90 hydrogel. Francis, an 11-year-old Yorkshire terrier, had a cancerous high-grade soft tissue sarcoma removed, but still had signs of cancer around the edges of removed tissues (known as dirty margins). Since his treatment in January 2022, Francis is thriving and remains cancer-free. Oliver, a 12-year-old domestic shorthair cat, had a fibrosarcoma in a limb. The limb was amputated, but the fibrosarcoma grew back at the amputation site. Oliver was treated twice with Y-90 hydrogel, most recently in July 2022, with no tumor recurrence to date.

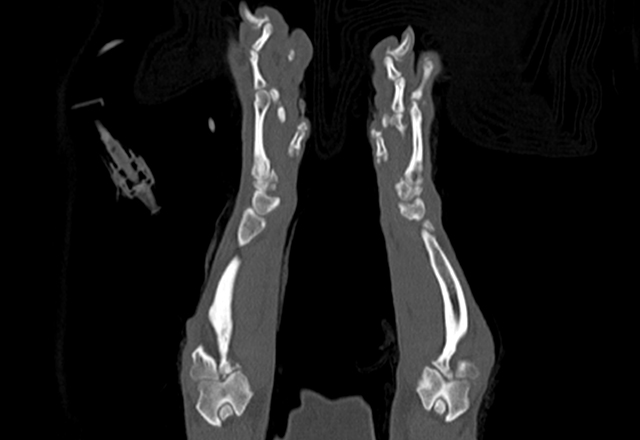

The other new radiopharmaceutical therapy, tin-117m, uses an isotope of tin in a colloid suspension to treat osteoarthritis in dogs, a common condition in older dogs. Osteoarthritis is a chronic degenerative condition associated with inflammation of the joint. Tin-117m injected into the joint cavity can cause a long-lasting reduction in the inflammation and pain associated with arthritis. A single intra-articular injection can provide relief for 12 months. Pets can be treated outpatient with tin117m and go home the same day. Humans should avoid prolonged direct contact with the injected joint(s) for two weeks following treatment. “When administered correctly, the treatment is very safe with no adverse reactions reported,” Krimins noted. With promising results, happy patients and pet owners, Krimins is hopeful that her work with radionuclide therapy in veterinary patients will offer new treatments and a better quality of life for pets as well as human patients.