Within the Johns Hopkins departments of neurology and neurosurgery, recent advancements in pediatric epilepsy care have resulted in vastly more precise and less invasive ways to diagnose, monitor and treat the source of seizures for patients with the condition. The department’s faculty members and clinicians are adept at caring for those with intractable epilepsy and for whom multiple medicines have failed.

“Our specialty is evaluating patients with difficult-to-control epilepsy,” says Sarah Kelley, director of the pediatric epilepsy monitoring unit, which opened in January 2020 and allows for quick admission and evaluation in a child-friendly environment. “We’re able to quickly bring patients in and give them the services they need.”

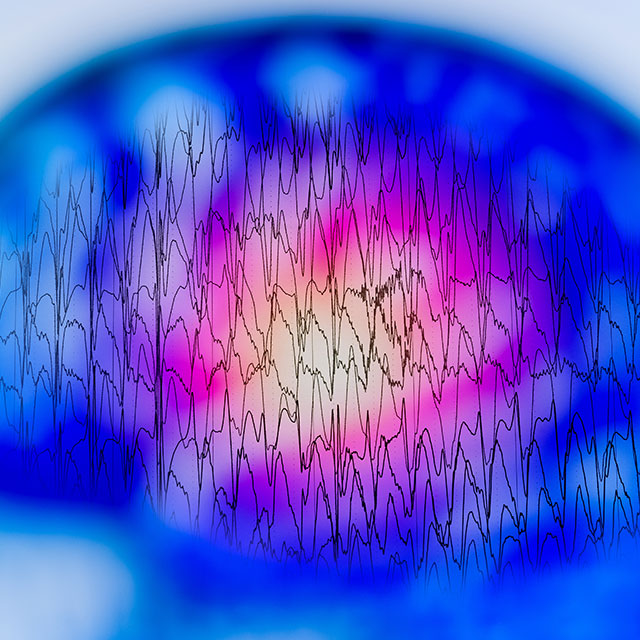

Along with high-resolution MRI, the care team uses stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG) technology, which involves placing tiny electrodes in the brain to pinpoint specific areas that cause seizures, allowing physicians 3D spatial and temporal imaging.

“Instead of having a large window of the skull removed, we make tiny holes in the skull using software and a robot,” says pediatric neurosurgeon Dody Robinson, who is a nationally recognized expert in the treatment of pediatric epilepsy and spasticity. “It adds a lot more precise information, and can help us potentially remove the area that’s causing the seizures.”

Laser ablation is also a treatment option for particular patients. The technique can be particularly effective for those with focal epilepsy. Rather than removing part of the brain with open surgery, Johns Hopkins neurosurgeons use laser ablation’s high-tech planning software and advanced imaging to create a tightly controlled, localized lesion. The care team has seen great efficacy in highly selected patients, Robinson says, and the approach reduces potential postoperative pain and cognitive issues, as well as the time children spend in recovery from several days for a typical open surgery to 24 to 48 hours.

The group is also treating certain pediatric patients with vagus nerve stimulators (VNS) and responsive neurostimulation (RNS).

In addition to intractable epilepsy and drug-resistant epilepsy, the departments’ clinicians specialize in treating patients who have already had surgery and continue to have seizures as well as patients looking for dietary therapy and other interventions.

Because of the collaborative and multidisciplinary nature of the work, pediatric patients have access to a breadth of opportunities for care. “We’re able to treat the patient holistically with our colleagues in neuropsychology and other specialties to really help these kids get as close to typical as possible,” Robinson says. “We have extensive resources in terms of helping the whole person. It’s very rewarding to be able to help these kids get their lives back.”