When businessman, investor and philanthropist David Rubenstein’s two daughters were in preschool decades ago, their teachers told him that his daughters weren’t paying attention as well as other children in class. After months of doctors’ appointments, tests eventually showed that both girls had congenital hearing loss of about 30%. Although each were fitted for hearing aids, they chose not to use them, Rubenstein says, relying instead on strategies such as reading lips and sitting close.

Now in his 70s, Rubenstein’s own hearing has declined due to his age, he says, strengthening his enduring interest in hearing loss. A longtime member of the Johns Hopkins Medicine board of trustees, Rubenstein says he knew exactly where to direct his gift when he donated $15 million to Johns Hopkins Medicine over five years — he earmarked the funds for hearing loss research and establishment of a professorship bearing his name in the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. Paul Fuchs, Ph.D., who has spent the last 25 years of his career at Johns Hopkins, is the inaugural David M. Rubenstein Research Professor of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery.

“My hope is that this gift will eventually make great strides for people with hearing loss, whether it’s born or acquired,” Rubenstein says.

Fuchs explains that his new professorship, along with grants from the National Institutes of Health and other sources, will help fund his salary, allowing him to devote more money to his research projects. “It allows us more flexibility for which research projects we pursue,” he says.

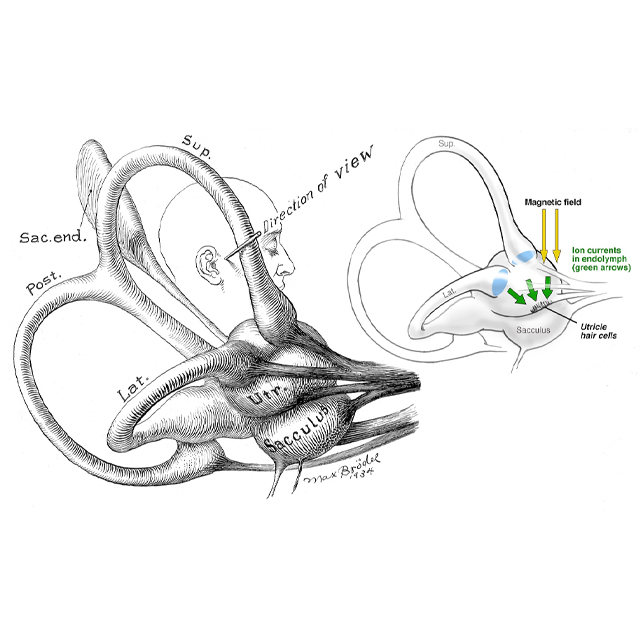

Fuchs has devoted some of this gift to investigations of afferent neurons that send sound information to the brain and efferent neurons that project from the brain back to the ear. His work has shown the existence of a feedback loop that appears to protect the ear from acoustic trauma by inhibiting the effects of loud sounds. He and his team are currently testing the possibility of an applied gene therapy that might protect hearing in noisy environments.

The majority of Rubenstein’s gift is in an endowment that funds “accelerator grants” for other investigators at Johns Hopkins — $100,000 grants that have the potential to speed up ongoing research projects. For example, Fuchs says, some of these grants have funded the work of Elisabeth Glowatzki, Ph.D., on ear reinnervation, reconnecting the sensory cells in the ear with the brain when those connections have declined or been lost. Other grants have funded research by Angelika Doetzlhofer, Ph.D., on encouraging support cells in the ear to morph into sensory cells — the death of these sensory cells is a major cause of hearing loss.

“We are all using these funds to help push our work forward, collaborate and grow expertise,” Fuchs says. “It’s a revolutionary gift that will have a big impact for years to come.”

To support the department's work, call 410-955-0173