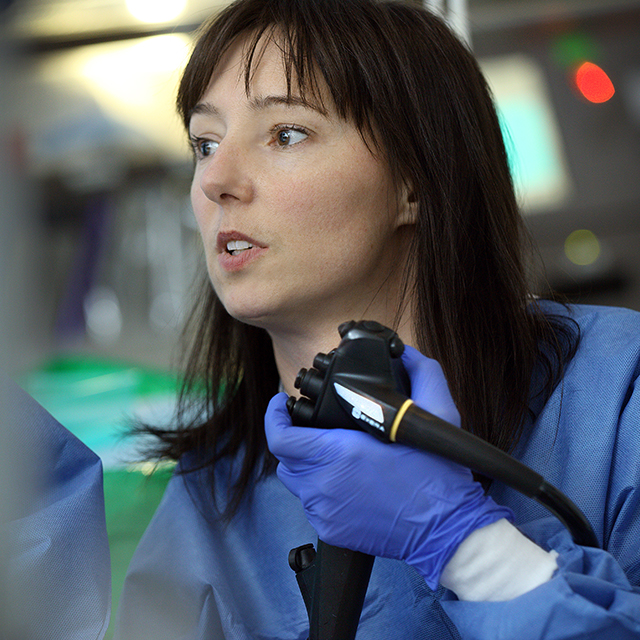

Johns Hopkins gastroenterologist Elham Afghani sees many patients whose pancreatitis has been diagnosed as idiopathic or unexplained. “A lot of them are told there’s nothing that can be done for them,” says Afghani. “By the time they decide to come to Johns Hopkins, they’re frustrated with ongoing episodes of acute pancreatitis or abdominal pain.”

But a growing field of research is providing clues to this mysterious condition. In the past few years, she says, genetic testing has revealed gene mutations that increase the risk of pancreatitis and are commonly found in patients with unexplained pancreatitis. The discovery of these genes has changed the way Johns Hopkins gastroenterologists approach the condition.

Afghani says that genetic testing has contributed to the Johns Hopkins team’s ability to identify the origins of a patients’ disease.

“We’ve seen a significant drop in the number of pancreatitis cases that are idiopathic,” says Afghani. We’re getting a lot more clarity, and it’s a great feeling to help patients get to the bottom of this problem.”

Many different conditions can lead to painful inflammation of the pancreas. Afghani says the first goal is to determine the underlying cause.

“Comprehensive genetic testing is done once all other major common etiologies have been excluded. Most patients with pancreatitis have both environmental and genetic contributions to their disease. Knowing whether genetic mutation is a factor can save patients from undergoing a lot of tests that can be difficult.”

For instance, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [ERCP], while vital in certain circumstances, can sometimes aggravate bouts of pancreatitis when used as a diagnostic tool.

“If we can look at a genetic workup and find a mutation of one of the genes associated with recurrent or chronic pancreatitis, then we have our answer and can move on to treatment options,” Afghani says.

The testing can also reveal other important determinants of health.

“For example, knowing whether a person has a mutation of one of the genes associated with pancreatitis can help us determine that person’s risk of developing complications of pancreatitis, including diabetes, exocrine insufficiency and, in some, pancreatic cancer,” says Afghani, adding that knowing about hereditary risk can also benefit a person’s family members.

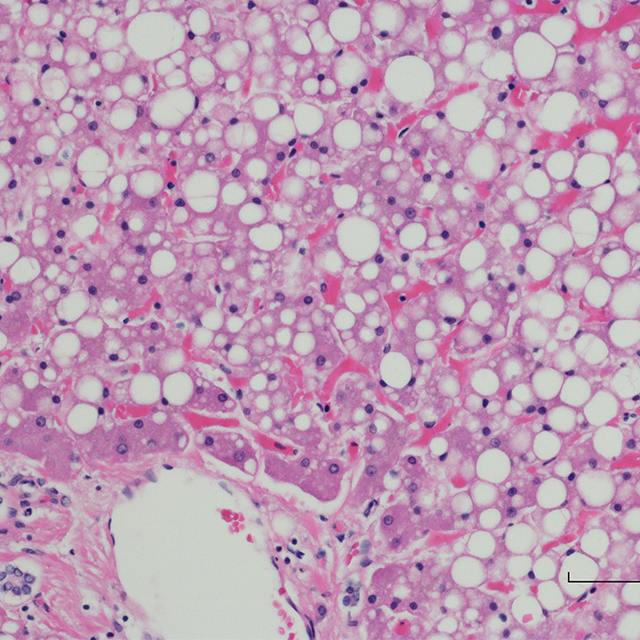

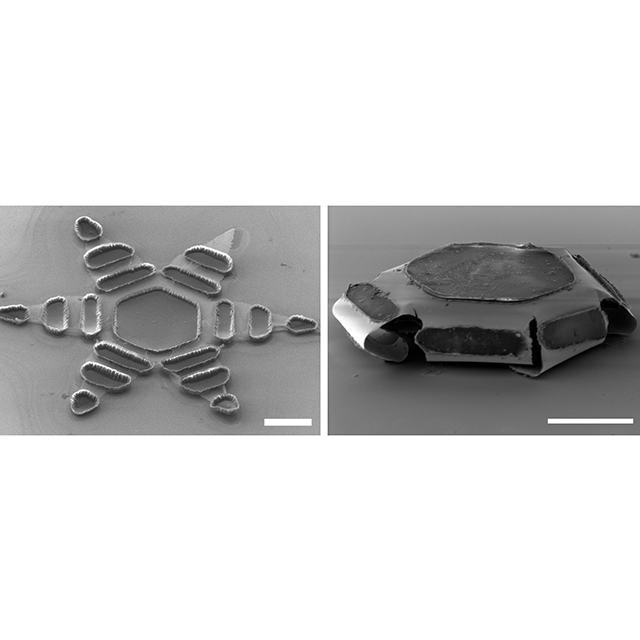

For patients whose pancreatitis does not respond to treatment, the Johns Hopkins Pancreatitis Center offers a surgery where the pancreas is removed, and the insulin-producing cells are harvested from the pancreas and transplanted to the patient’s liver, which they can continue to produce insulin. The multidisciplinary Total Pancreatectomy and Islet Autotransplantation Program brings together gastroenterologists, endocrinologists, radiologists and surgeons to make sure the transplantation succeeds.