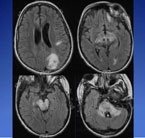

On MRI, MS lesions show up as bright spots revealing demyelination and on-going disease activity, even when a patient is in remission.

Pediatric neurology resident Sarah Aminoff Kelley had seen enough children who had experienced a demyelinating event without knowing for sure whether it was acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) or multiple sclerosis (MS). Treating such an initial attack may prevent future relapses and reduce the risk of disability in MS patients, she noted at a recent pediatric neurology grand rounds, but studies have not been done in children to identify the patients most likely to develop MS.

“We always tell parents that MS is a possibility but we don't have a good way to give them a more definitive answer as to how likely it will be,” says Kelley. “Then we follow these children with serial MRIs over time, but it is difficult to say when we should stop monitoring them or who we should monitor for a longer period of time.”

While ADEM is typically an isolated event, a clinical presentation consistent with ADEM can be the first manifestation of multiple sclerosis in children. Around 45 percent of children with a demyelinating event will have a second event, and 20 percent of children diagnosed with ADEM will progress to MS. To confuse matters more, 18 percent of children diagnosed with MS experience a clinical event consistent with ADEM or MS. Needless to say, Kelley noted, none of this makes prognostication easy after an initial event. But thanks to new criteria using MRI technology, pediatric neurologists may have an increased ability to detect demyelinating lesions due to MS – a step closer to distinguishing the two conditions after an initial event.

On MRI, Kelley explained, MS lesions show up as bright spots revealing demyelination and on-going disease activity, even when a patient is in remission. Lesions can be counted, measured, and even connected to cognitive problems with memory like word-finding or problem solving. Black holes on MRI reveal more extensive tissue loss, where demyelination used to be, and have been linked to permanent disabilities. Most of the findings, however, relate to adult criteria, which is not as sensitive – correctly identifying those with the disease – or specific – correctly identifying those not having the disease – in children. MS appears more aggressive in children on MRI but not necessarily clinically, Kelley reported, with more high-intensityT2 lesions appearing early.

So, what are the best diagnostic criteria that have surfaced from the few pediatric studies on the issue? Citing a Dutch study of 49 children comparing four sets of MRI criteria for diagnosing pediatric ADEM and MS (Neurology 2010;74:1412-1415), Kelley noted that the so-called Callen MS-ADEM criteria – two or more of (1) the absence of a diffuse bilateral lesion pattern, (2) the presence of black holes, and (3) the presence of two or more periventricular lesions – showed the best combination of sensitivity (75 percent) and specificity (95 percent).

While the criteria is useful, Kelley said, it’s not conclusive. Larger studies with more patients and controls to test the criteria need to be done. “The biggest surprise,” Kelley said, “is that we don't have enough well-designed studies to really determine the best approach for diagnosing and treating these children.”

The takeaway message for community pediatricians?

“It’s important for them to know that at this point we still do not have good tools for knowing which patients will develop MS after their first demyelinating event even if it is diagnosed as ADEM,” Kelley says. “Therefore, they should monitor their patients who have been diagnosed with ADEM for other neurologic problems and transient neurologic symptoms such as an eye that gets blurry for a few days and then gets better, or a leg that goes numb for a few days and then gets better. Asking about these things in regular clinic visits can help to pick up kids who may go on to develop MS.”