Visiting Scholars Come to Johns Hopkins All Children's for Top Research Experiences

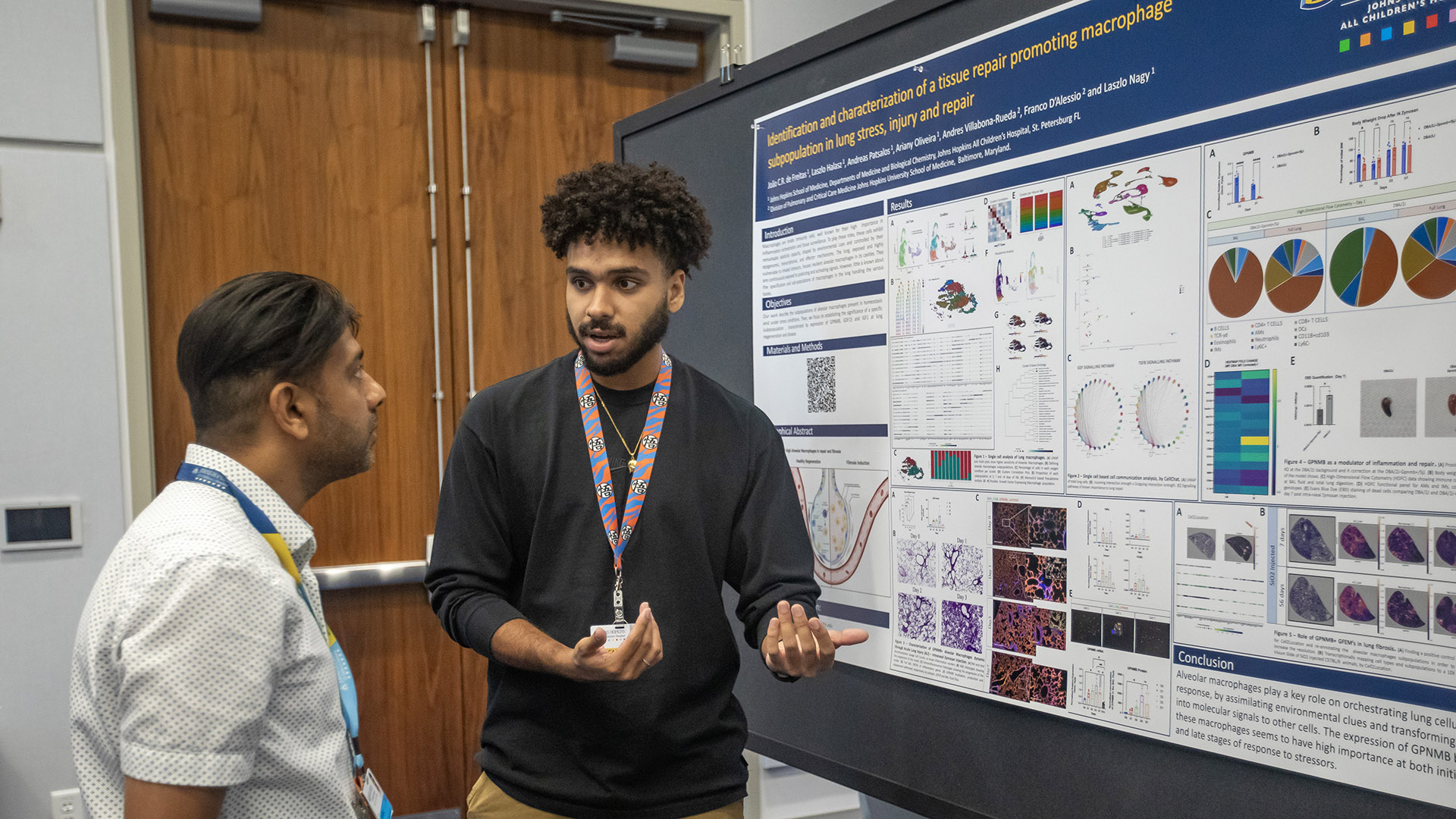

João Carlos Ramalho de Freitas with Laszlo Nagy, M.D., Ph.D.

Agnieszka Robaszkiewicz, Ph.D.

Agnieszka Robaszkiewicz, Ph.D.Besides being a world-class hospital for treating children, Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Florida, is also a thriving destination for academic growth. Increasingly, it is attracting talented scientists either for full-time roles or temporary visits as “visiting scholars.”

Researchers at Johns Hopkins All Children’s are well connected to the highest levels of current and innovative research and the talented scientists worldwide who conduct it through international collaborations, attendance at scientific conferences, and by publishing their research in prestigious international journals. These connections create not only a “global community of research” that facilitates sharing of data, but also encourages scholars and other high-level researchers to visit and spend time working in the laboratories of scientists who are working on research projects similar to or related to their own.

Johns Hopkins All Children’s Institute for Fundamental Biomedical Research and the lab of Laszlo Nagy, M.D., Ph.D., recently hosted two visiting scholars, each of whom were attracted by his experience, expertise and international reputation.

João Carlos Ramalho de Freitas, an undergraduate student at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, recently came to Johns Hopkins All Children’s to study because he was interested in the immune system and in bioinformatics, both of which are front and center at the Institute.

“My studies at the university raised my interest in having a better understanding of the immune system — not only as a defense mechanism — but also as a much broader system,” de Freitas recalls. “And I decided to try to discover how the immune cells can work, and work in addition to their protective functions. My adviser, who is one of Dr. Nagy’s collaborators, arranged for me to come to Dr. Nagy’s lab where many of the researchers work on immunity.”

Agnieszka Robaszkiewicz, Ph.D., is on sabbatical from her position as associate professor in the Department of General Biophysics, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, at the University of Lodz, in Lodz, Poland. She came to Johns Hopkins All Children’s because she had become familiar with Nagy’s work by having read many scientific publications by Nagy and his colleagues.

“I decided to contact Dr. Nagy and explore the possibilities of joining his group,” she recalls. “I received a fellowship, funded by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange, and began working in Dr. Nagy’s lab last year.”

João Carlos Ramalho de Freitas

“João Carlos Ramalho de Freitas is an absolutely outstanding undergraduate who decided to spend a year in my lab as part of his undergraduate training to carry out a project on the role of macrophages in lung regeneration following injury,” says Nagy, a professor in the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism in the Departments of Medicine and Biological Chemistry at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, co-director of the Johns Hopkins All Children’s Institute of Fundamental Biomedical Research and also head of the Johns Hopkins Center for Metabolic Origins of Disease. “My collaborator in Brazil, Dr. Marcello Bozza, said that de Freitas is the best student he has ever had.”

Discovering Immunity

João Carlos Ramalho de Freitas

João Carlos Ramalho de Freitas“It was in biochemistry class that I realized how much data can come from doing experiments with human cells,” de Freitas explains. “I was impressed by how much data we can produce but also realized how much relevant information might be getting lost because humans can only process so much data as compared to the computer. As I came across enormous, computerized data banks, I was able to understand them and, with the right set of tools, I found I could transform that data into knowledge. That’s the reason I decided to also focus on bioinformatics in addition to learning more about the human immune system.”

“João Carlos is a great example of the new generation of scientists, who can effectively combine wet lab biology research and bioinformatic based data analyses,” Nagy says. “João Carlos’s strengths include analysis of large single cell databases and building new mathematical models of complex biological processes. We took advantage of both of these skills during his stay and not only in his own project.”

Given his interest in immunity, de Freitas’ research focus during his stint in the Nagy lab was to investigate the role of “macrophages,” specialized white blood cells in the immune system that play a key role in defending against disease by helping clear the body of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. De Freitas was particularly interested in the role of macrophages in lung regeneration after injury, such as that caused by viruses and, particularly, fungi particles.

“I became interested in how immune cells react to and interact with other cells,” de Freitas says. “So, I set out to identify and define populations of cells that drive regeneration in lung tissue cells and looked at the role played by macrophages. Macrophages are big eaters! They receive lots of signals, and it is important to understand what each cell is expressing and then discover which cells are responsible for regeneration.”

De Freitas is also getting involved in CRISPR — short for “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats” — a technology that research scientists use to selectively modify the DNA of living organisms. In his project he “knocked down and knocked out” certain proteins involved in immunity to determine its impact at inflammation induction against certain types of stressors. He is also interested in what is called “bench-to-bedside” medical advances where experimental techniques can eventually be used in the clinic.

“I think that João Carlos has the right idea and game plan how to integrate biology, information technology and medicine,” Nagy says. “I think that he has a bright future ahead of him, because this the direction biomedical research is heading in the next decades.”

A ‘Taste’ for Baltimore

During his time in the Nagy lab, de Freitas travelled to the Johns Hopkins campus in Baltimore to present a poster on his work titled "Identification and characterization of a tissue repair promoting macrophage subpopulation in lung stress, injury and repair." He found he liked the city very much, and he especially enjoyed Baltimore’s culinary trademark — crab cakes.

Beyond science, he has a love for Brazilian music and played guitar until science began taking up most of his time. However, academics came as second nature to him as his mother and stepfather are both teachers. His father is a career officer in the in the Brazilian Navy who, in his official capacity, once visited the White House. From his military father, de Freitas said he learned a certain sense of “rigor” that he now transfers to his work as a budding scientist.

Soon back in Brazil, de Freitas will resume his studies at the university, but still maintain contact with Nagy and others in his lab by working remotely as they prepare for publishing the data he generated and his subsequent findings. He expects to graduate in February 2024.

Agnieszka Robaszkiewicz, Ph.D.

During her sabbatical, Robaszkiewicz has been investigating the role of heme-dependent transcription co-factor Bach1 — an important transcription factor that both regulates mechanisms involved in immunity and also functions in cardiovascular disease and cancer. Her work is in mouse-models and involves macrophage extended synergy.

“This phenomenon was previously described by Nagy’s group in the prestigious journal Immunity in which researchers focused on immunity and inflammation found that prior exposure to microenvironmental signals could fundamentally change the response of macrophages to later stimuli,” she explains. “Their work applies to the innate immune response of phagocytes, a type of white blood cell that engulfs bacteria, foreign particles, and dying cells to protect the body. Phagocytes are synergistically activated by numerous antigens through several receptors.”

For her, what is most exciting in that work is that macrophage contact with anti-inflammatory factors can prime these cells to escalate pro-inflammatory responses during bacterial infections. “The anti-inflammatory-induced hyperinflammation may also occur in vivo — in the body — such as during airway inflammation,” she further explains.

Investigating ‘Heme’

Her work during the sabbatical has also involved going beyond the known transcription factors in the anti/pro inflammatory synergy and includes investigating “heme,” iron-containing molecules important for many biological processes.

“I have been looking for new factors by making use of bioinformatic approaches and genomics, the branch of molecular biology concerned with the structure, function, evolution and mapping of genomes — the complete set of genes or genetic material in an organism,” she says. “Since inflammatory conditions and diseases are often associated with heme imbalance due to red blood cells, I focus on the heme-sensitive protein — Bach1 — that may act as transcription repressor. Other options are still to be discovered — such as how the molecular impact of Bach1 transcription controls pro- and anti-inflammatory macrophages, particularly at the gene enhancers and the recruitment of gene activators or repressors.”

“These are interesting and timely questions, and we have the right tools to address them,” Nagy says.

The Travels of an International Scientist

“I had never planned to become a scientist,” admits Robaszkiewicz. “But, after getting a master’s degree in biology, I decided to go further and, as I was always strong in physics and mathematics, I pursued a Ph.D. in biophysics. However, there were outstanding molecular biologists in our group who were focused on transcription control of gene expression, and I eventually shifted my scientific interest in that direction.”

She received her Doctor of Philosophy in biology/biophysics in 2012 and her Doctor of Science in biological sciences in 2019. She now has a long record of scientific publications and awards.

Robaszkiewicz’s time spent in the Nagy lab is not her only research foray outside of her native Poland. For example, from 2011 to 2013, she was a researcher in the Department of Medical Chemistry at the University of Debrecen in Hungary; from 2013 to 2014, she served as a researcher/post-doctoral fellow in the Institute of Veterinary Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the University of Zurich in Switzerland; in 2018, she completed fellowship and a scientific internship at the School of Life and Health Sciences at Aston University in Birmingham, in the United Kingdom; and, in 2022, she carried out a short-term scientific mission to study the “Identification of molecular signatures of multinucleated drug-resistant cancer cells for further targeting with nanotechnology,” at the Medical University of Graz in Austria.

Reflections on a Florida Experience

In ways other than those strictly scientific, Robaszkiewicz has found her research experience in Florida unique and meaningful.

“My husband and our 4-year-old daughter joined me in Florida two weeks after I arrived,” says Robaszkiewicz. “Being from Poland, Florida’s high temperatures were difficult for us, but we enjoyed being near the beach.” She adds that the family also found “the smiling faces” they saw on the streets of St. Petersburg to be “extraordinary.”

When she is back home at the University of Lodz, she will continue teaching, doing research, and advising master’s degree students as well as students who are working on their doctorates. As a principal investigator, she, and her colleagues, as well as the students she supervises, have been involved in a great variety of research projects, many of which are focused on immunity and other research projects that involve chemotherapy resistance.

“For example, we investigate transcription control of macrophage polarization during lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced macrophage tolerance where exposure to LPS triggers an inflammatory response, but repeated or prolonged exposure to LPS can induce endotoxin tolerance, where macrophages and monocytes do not respond to new challenges,” she explains.

What has she learned during her sabbatical at Johns Hopkins All Children’s?

“The most important things I learned during my sabbatical, and I can apply when I resume my position at the University of Lodz, have to do with supervising research group members' work, the need for organizing group meetings, and reviewing scientific literature,” says Robaszkiewicz. “These activities can help young, future scientists face and help solve various problems that emerge during research and while working with colleagues.”

“I find it scientifically and culturally enriching to host visiting scientists,” Nagy says. “These visits enrich both parties and often serve as a launching pad for long-term collaborations.”