For months, Ann O’Brien didn’t feel quite right. Her heart rate was lower than normal; her blood pressure was higher; she experienced abdominal pain; and her stomach felt distended.

A series of doctor appointments didn’t yield answers. Meanwhile, her symptoms continued, until one day in November 2020, the pain was so excruciating that she headed straight to her gynecologist’s office for a scan. The ultrasound revealed a 17-centimeter, 8-pound pelvic mass. O’Brien recalls the tech immediately running to get a doctor, who recommended she see a specialist.

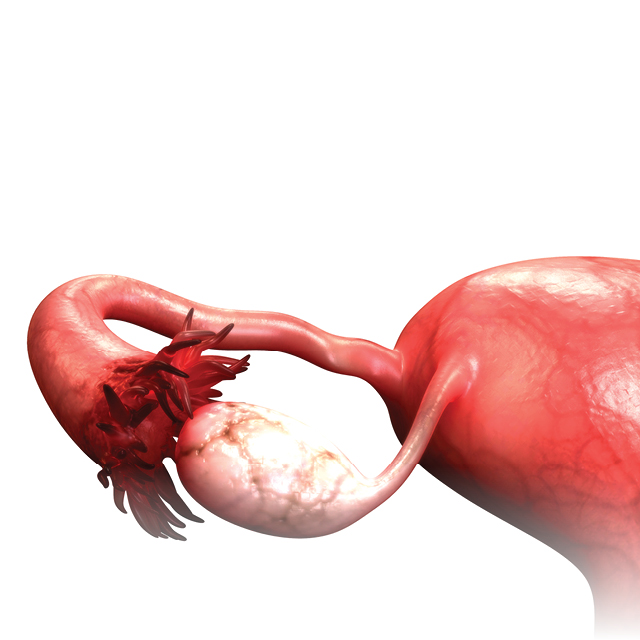

Days later, the mother of two, who was 46 at the time, met with gynecologic oncologist Jeanine Staples at the Sibley Memorial Hospital Center for Gynecologic Oncology and Advanced Pelvic Surgery. They planned a surgery called a salpingo-oophorectomy to remove the entire right fallopian tube and ovary, which is where the mass was arising from. Staples did not want to remove the mass alone because separating it from the ovary would increase the risk that it would rupture and cause seeding of potentially cancerous cells elsewhere.

As discussed with O’Brien, if the mass was found to be cancerous — information the team would learn during the surgery — Staples planned a more extensive procedure so the patient wouldn’t have to come back for a second operation.

A frozen section biopsy — a test that checks for the presence of cancer during an operation — found evidence of cancer, so Staples performed a full staging surgery. In order to determine the stage, it is standard of care to remove both fallopian tubes and ovaries; the uterus and cervix (a hysterectomy); the lymph nodes (a lymphectomy); and the omentum (an omentectomy), which is a layer of tissue on top of the intestines and other organs in the abdomen that ovarian cancer can spread to. There could be microscopic cells in these other organs that could change the stage of the cancer, which would have implications on the treatment plan and outcomes.

“When I woke up from the surgery, Dr. Staples was holding my hand, and I knew that probably wasn’t good,” O’Brien says.

Staples told O’Brien that the tumor was cancerous, and that she had performed the full surgery, but would have to wait for complete pathology results to know what kind of cancer it was and if it had spread.

It turned out to be a rare form of ovarian cancer — granulosa cell tumor — which accounts for 2%–5% of ovarian cancers and affects about 1 in 100,000 women in the United States per year.

As part of the routine surgery for ovarian cancer, the peritoneal cavity — the space that contains the intestines, stomach and liver — is washed with a saline solution that is later removed and tested for cancer cells. And while O’Brien’s granulosa cell tumor hadn’t visibly ruptured or spread, the final pathology report noted that there were microscopic cancer cells in the washings, making the cancer Stage 1C, for which chemotherapy is recommended.

Staples told O’Brien that “rare” didn’t necessarily mean bad in her case. The doctor’s choice of words comforted O’Brien throughout the process.

“The way Dr. Staples chose to deliver the news with positive words, both at the beginning and the end of the treatment journey, was really thoughtful,” O’Brien says. “It really had an impact on me. Your doctor can set the tone on your mindset — a positive mindset.” She adds that Staples’ words helped her speak to her teenage daughter and preteen son about the diagnosis.

Staples worked with Bruce Kressel, a medical oncologist at Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center at Sibley, and a multidisciplinary panel of experts to come up with a treatment plan.

“This is a rare cancer, but it’s treated along the same guidelines as other ovarian cancers,” Staples says. “We did the full staging surgery, and completed six cycles of chemotherapy.”

Following chemo, O’Brien had no evidence of disease, and now sees Staples every three months for a pelvic exam and blood work.

“Dr. Staples told me there’s no evidence of cancer; cancer is part of my medical history, but it’s in the rearview mirror, and we’re going to monitor it and keep moving forward,” O’Brien says. “And I told my kids that.”

Complex and rare cancer cases such as O’Brien’s are approached in a multidisciplinary manner at the Cancer Center. In addition to Staples, Kressel, and the pathologist who tested the frozen section, the case was reviewed in a biweekly multidisciplinary tumor board meeting, in which medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, pathologists and radiologists discuss cases together.

“Everybody gives their opinions, and we come up with a consensus,” Staples says. “We also see if there are any clinical trials that patients are eligible for. It’s really nice having this large group with different levels of experience. With that input, we can really feel confident going forward with a treatment plan.”

Staples says that because there is no good screening test for ovarian cancer, it’s important for patients to have a primary care provider or primary gynecologist with whom they can share any changes in health or symptoms they experience.