Prostate Cancer Diagnosis

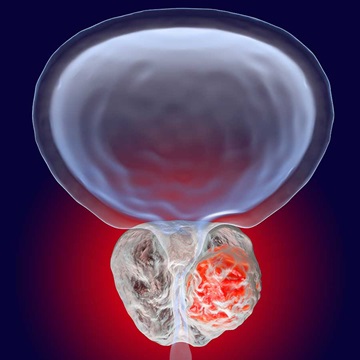

Diagnosing prostate cancer in time to treat it effectively is crucial. However, not all prostate cancers are created equal. Some are very slow-growing and never need treatment; others can be fatal within a matter of months after they are diagnosed. Just as important as finding cancer early is knowing which kind of cancer it is.

Your urologist will use your symptoms and the results of your screening tests to determine if diagnostic testing is needed. He or she may recommend a biopsy of the gland to confirm your diagnosis. Additionally, your urologist may suggest bone scans, computed tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to find out if the cancer has spread.

Biopsy

Prostate cancer is diagnosed with a prostate biopsy, which removes tissue from the prostate to examine it for cancer cells. This removal is guided by transrectal ultrasound, which uses a rectal probe to deliver ultrasound waves to the prostate and surrounding tissues.

A typical biopsy collects about 12 core samples from different areas of the prostate. Once the biopsy tissue is obtained, the pathologist examines it under the microscope. To diagnose prostate cancer, pathologists first examine the biopsy for abnormal, cancerous cells. If the pathologist sees cancer, the next step is to determine the grade of the cancer (how aggressive each cell looks under the microscope). The pathology report often includes information on how many biopsy core samples contain cancer as well as the percentage of cancer in each of the cores.

Some urologists use MRI combined with ultrasound technology to achieve a clearer biopsy target. Your physician may use an MRI-targeted prostate biopsy if you have had previous negative biopsies, worrisome features (e.g., an elevated PSA) and lesions visible on an MRI.

Potential complications from a prostate biopsy include:

- Blood in the urine

- Blood in the semen

- Infection in the prostate or urinary tract

- Rectal bleeding

Antibiotics are typically prescribed prior to a prostate biopsy in order to reduce the risk of an infectious complication.

Other Tests to Help Confirm Diagnosis

- Multiparametric-magnetic resonance imaging (mp-MRI): This advanced imaging technology may be used to detect, assess and stage prostate tumors.

- Prostate cancer gene 3 (PCA3) test: This is a urine-based prostate cancer test designed to look for the PCA3 gene. Higher quantities of this gene in the urine have been linked to prostate cancer.

- Prostate Health Index (PHI): This blood test calculates a score using different forms of PSA, generating more specific prostate cancer blood test results than the standard PSA test. It can provide additional information regarding elevated PSA levels while helping predict biopsy results.

Gleason Score

As normal prostate cells turn into tumor cells, their appearance changes under the microscope. The pathologist assigns the prostate cancer a Gleason score on a scale of 1 to 5 based on how much the cancer looks like healthy prostate tissue. The higher the Gleason score, the more abnormal the cancer cells appear.

The pathologist first scores the most common/prevalent type of cancer that he or she sees under the microscope. Then the pathologist looks for the next most common type. Adding these numbers together will yield the overall Gleason sum or score.

The American Cancer Society notes two exceptions to the standard rule:

- If the highest grade takes 95 percent or more of the biopsy sample, the grade for that area is counted twice. For example, if the pathologist only saw Gleason 3, then the Gleason score would be 6 (3+3).

- If three grades are present in a biopsy core, the highest grade is always included in the Gleason score. This is true even if most of the core is taken up by areas of cancer with lower grades.

For most prostate cancers, the Gleason sum ranges from 6 (3+3) to 10 (5+5):

- Gleason 6 is the least aggressive cancer type.

- Gleason 7 is intermediately aggressive.

- Gleason 8–10 is the most aggressive cancer type.

In general, cancers with lower Gleason scores are less aggressive while cancers with higher Gleason scores are more aggressive.

Partin Tables

The Partin tables, tools developed by Johns Hopkins researcher Alan Partin, M.D., are designed to help patients and their doctors understand the extent of prostate cancer and guide treatment options. Factors that go into the Partin Tables include the patient’s PSA levels, Gleason score and clinical stage.