Women Gaining Access to Medical Education

Founders’ Early Attitudes

During the 1890s, women were generally excluded from medical education. So people were understandably shocked when word spread in 1893 that there were three women in Johns Hopkins' first medical school class.

Admitting them was revolutionary, but Johns Hopkins' founders did not consciously set out to expand opportunities for women. Although Daniel Coit Gilman, the University's first president, pushed for first-class schooling for women (and helped found Goucher College in Baltimore), he sided with his friend Charles Eliot, president of Harvard University, who called coeducation (women learning alongside men) "a thoroughly wrong idea, which is rapidly disappearing."

Likewise, the medical school's first professor and dean, William Henry Welch, privately told friends he would be too embarrassed to discuss medical matters with a woman sitting in his lecture hall. And the idea of admitting women never seemed to have occurred at all to the medical institutions' chief planner, John Shaw Billings, who, in all his writings of the future medical school, referred to medical students solely as "young men."

Thomas, Garrett, King and Gwinn: A Turning Point

Mary Elizabeth Garrett

Mary Elizabeth Garrett

Unforeseen events forced the founders to rethink their views in 1890. The medical school was supposed to have opened at the same time as the hospital, in 1889, but it turned out there was no money for it. Income from the university's B&O Railroad stock, which Johns Hopkins had expected would cover operating costs, had dried up the year before.

Despite the delay, Hopkins trustees had lined up the school's four premier professors. When the doctors showed up, there was no school to teach in, and Harvard, McGill and the University of Pennsylvania tried to hire them away.

So Hopkins leaders listened when four of the original university trustees' daughters — Martha Carey Thomas, Mary Elizabeth Garrett, Elizabeth King and Mary Gwinn — offered a deal. They would raise the $500,000 needed to open the school and pay for a medical school building, but only if the school would open its doors to qualified women. Reluctantly, the men agreed.

Mary Elizabeth Garrett Boardroom Honors a Johns Hopkins Legacy

In 2018, a boardroom in the Miller Research Building on the East Baltimore campus was renamed the Mary Elizabeth Garrett Boardroom, paying homage to the woman who spearheaded an ambitious fundraising campaign that helped finance the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in 1893.

A Higher Standard for Medical Students

When the money was in hand by Christmas Eve, 1892, the Women's Fund Committee added a strategic twist. Garrett, the daughter of the head of the B&O Railroad, was able to donate about $307,000 to the effort herself. She presented a list of entrance requirements that would have to be met by any Hopkins applicant, male or female: proof of a bachelor's degree, proficiency in French, German and Latin, and a strong background in physics, chemistry and biology.

Most of the criteria echoed those from an early letter by Welch to university president Gilman — suggestions that even Welch admitted might be too stringent.

"She naturally supposed this was exactly what we wanted," Welch wrote of Garrett to his colleague, Harvey Cushing, in 1922.“We were alarmed, and wondered if any students would come or could meet the conditions, for we knew that we could not. As Osler said, ‘Welch, it is lucky that we got in as professors; we could never enter as students.'"

Thus, the women revived ideals that were almost shelved, and ensured that Hopkins would set a new, unprecedented standard in American medical education.

Women’s Presence Increases

But first, the committee needed help, on a national scale. Julia Rogers recruited fundraising support from among the nation's most influential and wealthy women, including First Lady Frances Cleveland, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell (the first woman ever to graduate from an American medical school, the Geneva College of Medicine in upstate New York, in 1849), Julia Ward Howe, Alice Longfellow, Clara Barton, Mabel Gardiner Hubbard Bell, and others.

In the end, Welch was the only Hopkins doctor who declined to sign a letter asking the trustees to accept the women's offer of financial help.

Though two of the first three women medical students dropped out, the third, Mary S. Packard, a Vassar graduate, completed the program and received her medical degree. By the turn of the century, even Welch had learned the value of women’s presence in medical classrooms.

"The necessity for coeducation in some form," he wrote later, “becomes more evident the higher the character of the education. In no form of education is this more evident than in that of medicine.... We regard coeducation a success; those of us who were not enthusiastic at the beginning are now sympathetic and friendly.”

As women were in part responsible for Johns Hopkins’ standards of excellence, they made sure women students met them. When the intellectual novelist Gertrude Stein attended the medical school, she didn’t complete her course requirements and failed at a major research assignment in obstetrics. Florence Sabin, then a resident, was asked to review Stein’s work, and decided it was substandard. Stein was out.

Other Women of Distinction in Johns Hopkins’ Early Days

Florence Sabin

Florence Sabin

Florence Sabin

Florence Sabin earned her M.D. at Johns Hopkins in 1900, and in 1917 was the first woman appointed full professor in the School of Medicine. She headed Colorado’s public health department from 1944 to 1953, and a bronze statue of Sabin stands in the gallery of the U.S. Capitol honoring her many contributions to anatomy and histology.

Sabin had raised the ire of fellow anatomists by presenting experimental results that cast doubt on the prevailing theory of how the lymphatic system is formed. Her tenacity and indisputable demonstrations led to worldwide acceptance of a new view of lymphatic development. Sabin was the first woman elected to the National Academy of Sciences, in 1925, and the first woman president of the American Association of Anatomists.

Helen Taussig

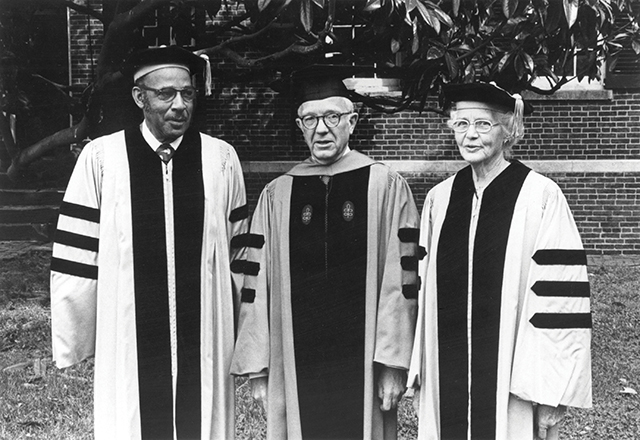

Dr. Taussig (right) pictured with Vivien Thomas (left).

Dr. Taussig (right) pictured with Vivien Thomas (left).Helen Taussig earned her M.D. at Johns Hopkins in 1927. A pediatric cardiologist, Taussig, along with Alfred Blalock and Vivien Thomas, pioneered and performed the first "blue baby" operation for defective hearts, launching the field of modern heart surgery.

Noted for her gentleness and warmth with young patients and their parents, Taussig overcame dyslexia to become perhaps the best-known woman physician in the world. She advanced the understanding of how normal and congenitally abnormal hearts function, and her warnings about the drug thalidomide in 1962 are largely responsible for preventing deformities in American newborns.

Taussig was also the first woman member of the Association of American Physicians and the first to be awarded its George M. Kober Medal. She received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Lyndon Johnson.

Caroline Bedell Thomas

Caroline Bedell Thomas

Caroline Bedell ThomasCaroline Bedell Thomas earned her M.D. in 1930 at Johns Hopkins. Thomas was a cardiologist who developed the first preventive treatment for a major form of heart disease by using the drug sulfanilamide to break the destructive cycle of rheumatic fever. She also designed one of the nation's longest-running studies to find early predictors of disease, suicide and long life. Thomas was one of the first women elected to the Association of American Physicians.