Who Was Johns Hopkins?

Johns Hopkins was born on May 19, 1795. Raised as a member of the Society of Friends (Quakers), Johns Hopkins was known as an honest man, generous to a fault, somewhat stubborn, and hard with a bargain. He transformed himself from a grocer’s helper to a millionaire banker, and became Victorian Baltimore’s greatest philanthropist.

Previously adopted accounts portray Johns Hopkins as an early abolitionist whose parents had freed the family’s enslaved people in the early 1800s. New research has uncovered census records that indicate enslaved people were among the individuals living and laboring in Johns Hopkins’ home in 1840 and 1850, with the latter document denoting Johns Hopkins as the slaveholder. Other new findings documented additional links between the Hopkins family and slavery, as well as indentured servitude. Researchers are investigating these records in tandem with other archival documents to offer a more nuanced and complex understanding of the Hopkins family’s relationship with slavery. More information about the university’s investigation of this history is available at the Hopkins Retrospective website.

Early Life

Though some mistakenly refer to the man or his institutions as “John” Hopkins, the “s” in his name belongs there: He was named for his great-grandmother, Margaret Johns, the daughter of Richard Johns, who owned a 4,000-acre estate in Calvert County, Maryland. Margaret Johns married Gerard Hopkins in 1700; one of their children was named Johns Hopkins. The second Johns Hopkins is the subject of this story.

Contrary to local legend, he was not born poor. The second of 11 children, he grew up in Whitehall, a sprawling tobacco farm in Anne Arundel County, MD, that the King of England had given his great-grandfather.

At 17, he realized the farm was not big enough to support his large family, so the young Hopkins moved to Baltimore to help his father’s brother, a wholesale grocer. Even as a young man, Hopkins was good with numbers and a fast learner.

While staying with his aunt and uncle’s house, Johns Hopkins fell in love with their daughter, Elizabeth Hopkins, then 16. She returned his feelings, admired his kindness toward women and children, and respected how he had helped her father and the family business.

They wanted to marry, but Quaker tradition forbade marriage between cousins. Johns and Elizabeth gave up on their dream of being husband and wife, but promised one another neither would ever marry anyone else. The two remained lifelong friends, Elizabeth living to age 88 in a house he had built for her at St. Paul and Franklin streets.

With a future of family life out of reach, Johns Hopkins turned his attention to business.

Early Business Ventures

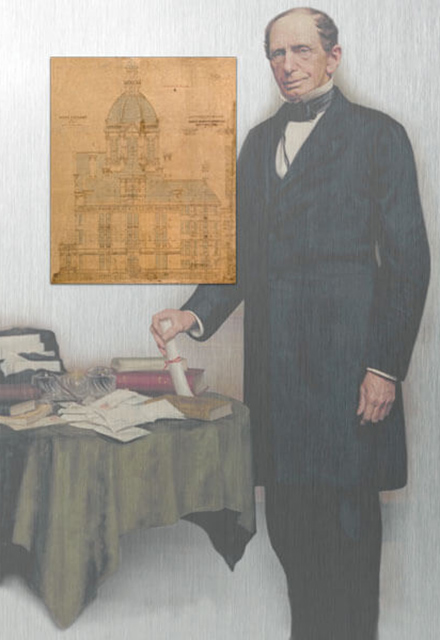

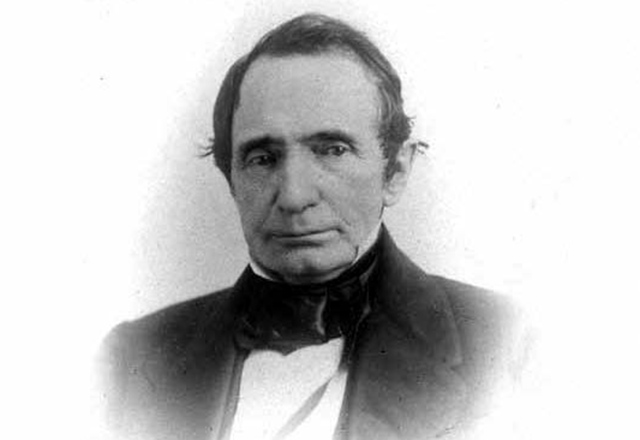

Johns Hopkins at the age of 40.

Johns Hopkins at the age of 40.George Peabody, another Baltimore philanthropist, was said to have claimed he knew of only one man more bent on making money than he himself was, and that was his friend Johns Hopkins.

Johns Hopkins had had a disagreement with his uncle, Elizabeth’s father, over the grocery’s customers paying for their orders with liquor, since money was hard to come by. The younger man thought this was a reasonable arrangement; his uncle refused to “sell souls into perdition” by letting them use alcohol as currency.

So Hopkins left his uncle’s house and business and went into business for himself with a young partner, and later with a few of his brothers. Together, they became a highly successful supplier of tobacco and other provisions and conducted business at the corner of Pratt and Hollingsworth.

For a while, the young men sold corn whiskey, under the label “Hopkins’ Best.” (Tradition says that the Quakers kicked Johns Hopkins out as a result, but later, took him back. He said later that he regretted selling hard liquor in his youth.)

Amassing a Fortune in Commerce

As a maturing businessman, the tall, craggy-featured merchant dressed simply, yet lived well. He divided his time between his country house, Clifton, where he entertained the Prince of Wales and other notable people, and a colonial rowhouse on West Saratoga Street. (Clifton was sold to the city in 1895 and the house served for many years as the Clifton Park Golf Course’s club house. Today, Clifton is home to Civic Works, a nonprofit youth training corps.)

Hopkins' country home, Clifton, located in a then-rural area northeast of the downtown.

Hopkins' country home, Clifton, located in a then-rural area northeast of the downtown.As his wealth accumulated, Hopkins began to lend money and shifted his interests into banking. Hopkins was made president of the Merchants’ National Bank of Baltimore, and was a director in the First National, Mechanics’ Central, National Union, Citizens’ and the Farmers and Planters’ banks.

He also was a director of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and owned at least 15,000 shares of stock in the railroad, more than anyone other than the City of Baltimore and the state of Maryland. He believed so much in the B&O that he spent almost $1 million to bail it out of financial trouble in 1857 and again in 1873.

Scharf’s Chronicle of Baltimore described his efforts to save the B&O from collapse, saying “[Hopkins] had large investments, all of which were affected by the unexpected crisis, but he would devote his money and his influence to avert the panic from the business community of Baltimore. This he was able to do….”

Hopkins offered low-interest loans to young men starting in business but charged higher rates to wealthy men who needed money. This practice made Hopkins less than popular among some people in the business community. When Hopkins died of pneumonia on Christmas Eve, 1873, his critics in town spread rumors that he had died because he was too cheap to buy himself a winter overcoat.

Giving to Others

As he grew older, Hopkins looked for ways to use his wealth to benefit others, since he had no wife or children to inherit his money. He arranged to leave much of his money and property, such as rental houses, warehouses and stores, to surviving relatives and three of his servants. But his legacy planning did not stop there.

No one knows how he came up with the idea to found a university linked to a hospital, though there is ample evidence he turned to friends for advice. He may have been influenced by fellow philanthropist Peabody, who had founded the famed Peabody Institute in Baltimore in 1857.

Hopkins’ vision was a hospital that would be linked with a medical school, which in turn was to be part of a university, a radical idea that later became the model for all academic medical institutions.

He appointed a 12-member board of trustees, comprising local thought leaders, to carry out his vision. They, in turn, created an environment that attracted top educators and medical professionals to direct the university and hospital. By 1867, Hopkins had arranged for his bequest to be split evenly between the two institutions.

In his last months of life, Hopkins laid out clearly what he had in mind for his hospital. Here are some details from his explanatory letter to his trustees:

“It is my wish that the plan…shall provide for a hospital, which shall, in construction and arrangement, compare favorably with any institution of like character in this country or in Europe…

“The indigent sick of this city and its environs, without regard to sex, age, or color, who may require surgical or medical treatment, and who can be received into the hospital without peril to the other inmates, and the poor of this city and state, of all races, who are stricken down by any casualty, shall be received into the hospital, without charge.… You will also provide for the reception of a limited number of patients who are able to make compensation for the room and attention they may require…you will thus be enabled to afford to strangers, and to those of our own people who have no friends or relatives to care for them in sickness, and who are not objects of charity, the advantage of careful and skillful treatment.

“It will be your especial duty to secure for the service of the hospital, surgeons and physicians of the highest character and of the greatest skills…

“I wish the large grounds surrounding the hospital buildings…to be so laid out with trees and flowers as to afford solace to the sick and be an ornament to the section of the city in which the grounds are located…

“It is my special request that the influences of religion should be felt in and impressed upon the whole management of the hospital; but I desire, nevertheless, that the administration of the charity shall be undisturbed by sectarian influences, discipline, or control. In all your arrangements in relation to the hospital, you will bear constantly in mind that it is my wish and purpose that the institution should ultimately form a part of the medical school of that university for which I have made ample provision by my will …”

Johns Hopkins died on Christmas Eve 1873, leaving $7 million to the university and hospital that would bear his name. It was, at the time, the largest philanthropic bequest in U.S. history.