Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Students Help Asylum Seekers Navigate Health Care System

Navigators assist with scheduling medical appointments and using Baltimore’s transportation systems.

Before Coralia received help from health navigators at the Refugee Health Partnership (RHP), she says her life was complicated, stressful and frustrating. Since she didn’t speak English and had no vehicle, it was difficult to schedule and then find transportation for medical appointments.

“I thank God almighty for meeting people with nice hearts because, for me, it was a blessing that came into my life when I needed it most,” says Coralia, an asylum seeker from El Salvador.

The RHP is a health advocacy group at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine that focuses on education, community outreach and clinical work for asylum seekers and other forced migrants. The group collaborates with Asylee Women Enterprise (AWE), a Baltimore organization that supports asylum seekers, foreign-born trafficking survivors and other displaced people as they navigate the legal immigration process, heal from past trauma and rebuild their lives in Maryland.

AWE identifies clients with complex medical needs. Through the RHP-AWE Refugee Health Partnership Health Navigation Practicum, clients are matched with school of medicine students who act as health navigators. Over the course of an academic year, the students conduct health needs assessments with the clients and help set and meet their health-related goals. They also assist with setting up medical appointments and help clients navigate Baltimore’s transportation systems.

“Many of our clients urgently need medical care,” says Laura Brown, AWE’s executive director. “Some have untreated physical and behavioral health concerns as a result of violence suffered in their home country, while others need care related to trauma experienced during their journey to the U.S. Accessing the care they need can be extremely challenging. Most of our clients aren’t eligible for health insurance, don’t speak English and are unfamiliar with the U.S. health care systems.”

Brown says the health navigators assist with various activities such as making dentist or gynecologist appointments, getting updated vaccinations and finding mental health support.

C. Nicholas Cuneo, a Johns Hopkins physician, is the medical director of the HEAL Refugee Health and Asylum Collaborative, which supports the Health Navigation Practicum. In addition to serving as the students’ faculty adviser, he provides primary care to many of the patients enrolled. Between these two roles, he has seen firsthand the impact the program can have on both sides.

“It’s a win-win situation,” says Cuneo. “While the students gain invaluable insight into the patient perspective, their support and advocacy can be transformative for patients at a time when they need it the most.”

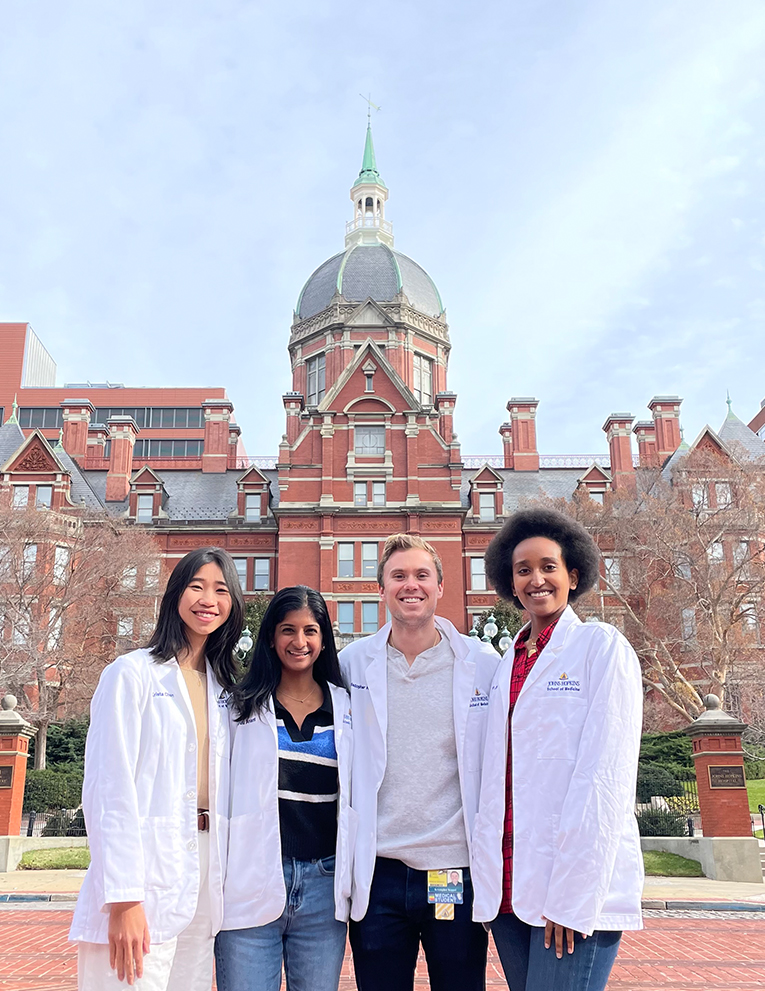

Health navigator and third-year medical student Shruti Anant says working with the Refugee Health Partnership has helped her understand that health care doesn’t always start or stop at the hospital.

“We help uncover misunderstandings, address real language barriers and provide health literacy education that makes a world of difference,” Anant says.

For third-year medical student Leila Habib, becoming a health navigator helped her appreciate the nature of relationships that transcend language and cultural barriers.

“Whether it’s singing in the car together on the way to an appointment, being introduced to the client’s family on a video call in the waiting room or trying out silly Snapchat filters for selfies together after a health visit, it’s those moments of shared humanity that I remember most deeply and fondly,” Habib says.

Third-year medical student Krista Chen says becoming a health navigator has been motivating and has added more depth to her medical school experience.

“We see the clients’ experiences and sit with them through both the frustrations and successes of existing within a limited health care system,” Chen says. “We get to know them as individuals, and it reminds us of the work still to be done.”

Being a health navigator has shown third-year medical student Kristopher Keppel that even the smallest acts impact clients’ health.

“They’ve often already faced so much adversity in their journey to get here, and yet once they arrive, there’s very minimal infrastructure to connect them with the care they need,” Keppel says. “Just accompanying them to an appointment or walking them through the process of refilling and picking up medications can change the trajectory of their health care journey. I think that’s been an inspiration for me and everyone involved to do more.”

For more information about the Refugee Health Partnership, visit source.jhu.edu/get-involved/partnering-student-groups/student-groups-in-the-school-of-medicine.