Retired X-Ray Tech Reflects on Changes in Field

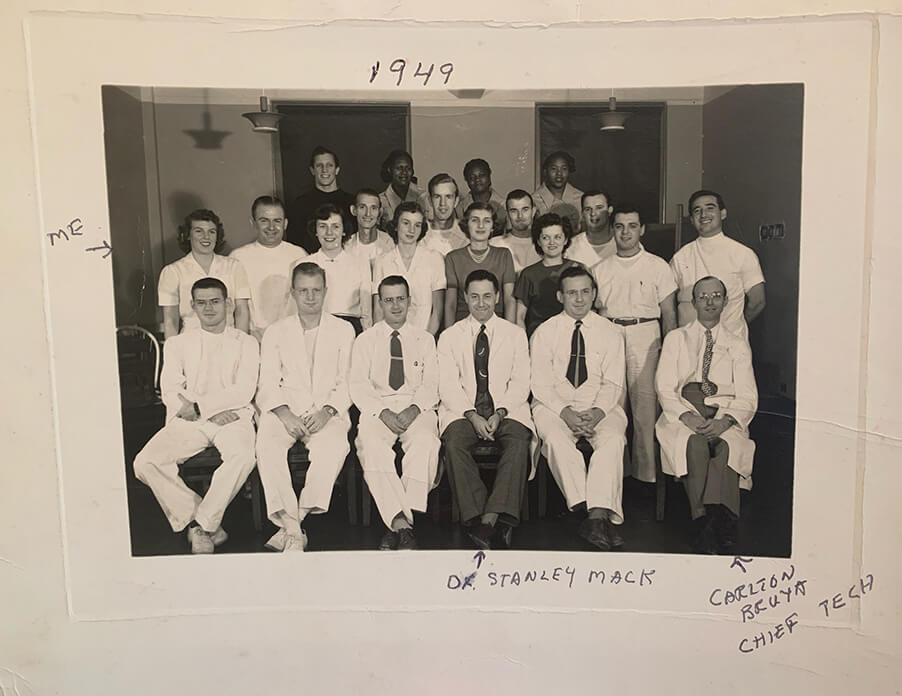

Elsie Protani (second row, first from left) with her class at Baltimore City Hospitals, now Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, 1949

X-ray imaging technology has changed a lot over the past 74 years — just ask Elsie Protani. The 93-year-old former X-ray tech has witnessed much of it with her own eyes.

Protani had the chance to visit her old stomping grounds during a recent visit to Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. While in the imaging department for fluoroscopy, Protani shared stories with staff members of her days as an X-ray tech. When she was asked if she would like to watch the procedure on the screen, she jumped at the opportunity. She was fascinated by what she saw, and at how far imaging has come within her lifetime.

“I think my mouth stayed open for a couple of weeks after,” she said.

Protani began training at the then-Baltimore City Hospitals (now Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center) in February 1948.

“Things were so different then,” she said. During an interview, the superintendent of Baltimore City Hospitals warned Protani of the “wild residents” just out of medical school.

Life as a student tech was tough. After the first two months of training, Protani began working on-call at night. It was there, she said, that you “learned to figure things out yourself.”

The night shift was often chaotic. A variety of mishaps and illnesses kept techs busy, while orderlies — many of them former merchant marines — helped keep tabs on unruly patients.

“If you worked there at the time, you could work anywhere,” she noted.

There were stark differences in X-ray techniques then versus now.

To take an angiogram, they had a school chalkboard 14- to 16-inches wide with a sawtooth wooden bottom. Putting an 8x10 cassette in one end, one tech would hold a stopwatch and another held a broom handle. When the radiologist said shoot, the tech would use the broom handle to push the films through.

“We thought we were being sophisticated,” Protani recalled with a chuckle.

During those early years, Protani worked 5½ days a week and on-call weekends, often getting by on catnaps while exposures were developing in the darkroom. During those years, she also married and started a family, which would grow to include four children.

Starting out in the late 1940s, Protani was in the minority as a female X-ray tech. Many of the students coming in were men fresh off the front lines of World War II, taking advantage of the GI Bill.

She recalled that the Johns Hopkins program had more female techs than most other programs. This built upon the historical precedent set by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine at its founding in 1893 that women should be given opportunities on an equal basis with men. Today, Johns Hopkins remains committed to fostering female leadership, within the radiology department and across the health system.

By the 1960s, more women were entering imaging, Protani said, and female X-ray techs became more common across the field.

In the early 1950s, Protani left Baltimore City Hospitals. She would go on to be the first female X-ray tech at the now-closed Ft. Howard Veterans Hospital. She would then work in private practice until retiring in 1970 to help her husband run a family business.

Looking back on her career as an X-ray tech, Protani explained that it was truly her calling.

“I loved every minute of it,” she said.

“I have a lot of fond memories,” she said, adding, “If I had to do it over again, I would.”