Members of the COVID-19 Pandemic Anchor Strategy Work Group, left to right: Nicole McCann, Tina Tolson, Sherita Golden, Panagis Galiatsatos, Alicia Wilson. (Photo: Keith Weller)

Peering at his computer screen, Panagis Galiatsatos assesses the new seating arrangement of a Baltimore church. He’s pleased to see that congregants will be spaced more than 6 feet apart, as recommended to prevent the spread of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Since March, the pulmonary and critical care doctor and co-founder of Medicine for the Greater Good has been participating in frequent telephone and video conversations with leaders of local churches, synagogues and mosques. In the early days of the pandemic, they discussed how COVID-19 information could be added to virtual sermons. Now, the focus is on safely reopening the sanctuaries.

“The front-line people are not the doctors and nurses,” says Galiatsatos. “We are the last line. The community is the front line. The more the population can spread proper information and not spread the virus, the better we can be at putting an end to this pandemic.”

Better Health for All

The conversations are part of a multipronged push by Johns Hopkins Medicine and The Johns Hopkins University to tackle a particularly troubling aspect of the COVID-19 pandemic: the disproportionate harm it is causing to already disadvantaged communities, particularly African American and Latinx people.

The effort, called the COVID-19 Pandemic Anchor Strategy, brings information and testing to Baltimore neighborhoods, provides additional bilingual support for Spanish-speaking patients, distributes food, and opens crucial lines of communication with community residents and leaders.

“You can give people medicine, but if you’re not meeting their basic needs you’re not really treating the whole person,” says Sherita Hill Golden, vice president and chief diversity officer at Johns Hopkins Medicine and a member of the Pandemic Anchor Strategy group.

Disparities Didn’t Start with COVID-19

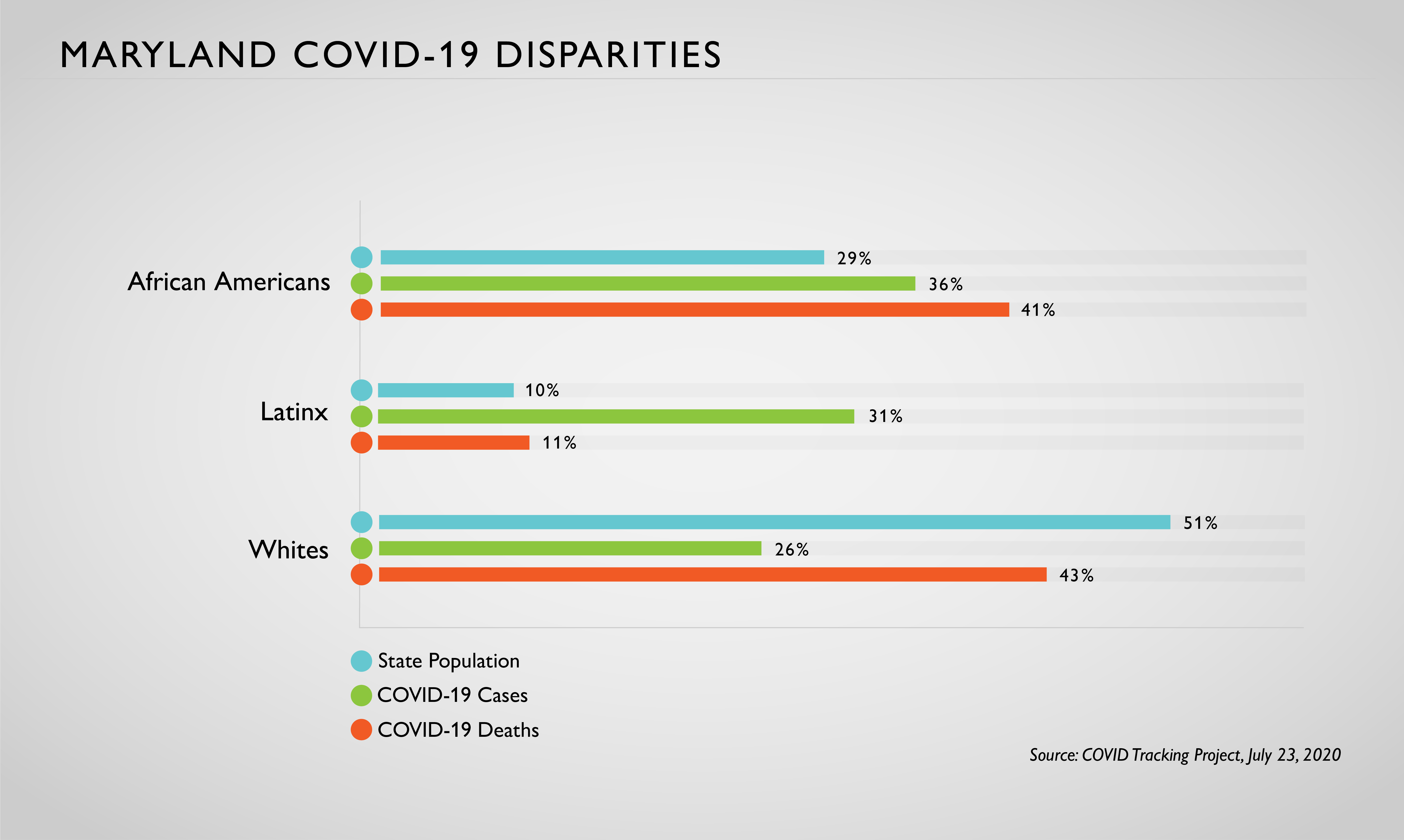

The COVID Tracking Project, which documents racial and ethnic disparities by state, shows that African Americans and Latinx people are at greater risk of COVID-19 harm compared to whites in Maryland.

African Americans, at 29% of the state’s population, account for 41% of COVID-19 deaths and 36% of cases. Latinx people, at 10% of the population, account for 11% of deaths and 31% of cases.

White people, at 51% of the population, make up 43% of deaths and 26% of cases. Native Americans, severely hit nationwide, are less than .05% of the state’s population — too few to show up in the tracking project’s data.

The factors contributing to these health disparities were entrenched long before COVID-19, says Golden.

Because of systemic racism that influences medical systems and social policies, she says, people of color are disproportionately distrustful of health care institutions and more likely to live in neighborhoods with poor access to green spaces, healthy food, and safe and affordable housing. For those reasons, they are more likely to develop conditions like asthma, diabetes and cardiovascular disease, which can worsen COVID-19’s toll.

The same people are at particular risk of infection from the coronavirus because they more often have low-paying jobs that don’t allow the luxury of working from home or taking time off. They are also more likely to live in densely populated neighborhoods and in close quarters with extended family, making physical distancing a challenge.

Latinx patients and families may also experience language barriers that hinder appropriate education, testing or care.

And the pandemic makes communication in health care settings even more difficult. With face masks and noisy powered air-purifying respirators, speech is harder to understand. Also, visiting restrictions mean family members can’t be there to comfort their loved ones.

The Pandemic Anchor Strategy

In March, as The Johns Hopkins Hospital began treating its first patients who had COVID-19, Alicia Wilson, vice president for economic development at The Johns Hopkins University and Johns Hopkins Heath System, was thinking about how to take the hospital’s response to the pandemic beyond its walls.

With the support of Johns Hopkins University President Ronald J. Daniels and Johns Hopkins Health System President Kevin W. Sowers, she brought together health system and university leaders to form the COVID-19 Anchor Strategy Work Group.

The group identifies, develops and deploys interventions in coordination with the Baltimore school system, the city and state health departments, and other agencies and organizations to bring education, testing and other resources to Baltimore communities that are particularly hard hit by the pandemic.

The efforts so far include:

· Connection and Education. Johns Hopkins experts have led phone and video conversations and town halls with clergy members, parents, students and older adults on topics such as how to entertain children during the summer, and legal rights in case of eviction. Virtual movie nights, TikTok competitions and trivia games, offered in English and Spanish, provide more opportunities to build connections with young people. Flyers distributed in English and Spanish give information about physical distancing, mask wearing and other safety measures.

· Culturally Appropriate Care. A new program called Juntos seeks to reduce cultural and language isolation for Latinx patients and their families by connecting them with bilingual clinicians. “Having someone speak to the patients directly in their primary language is comforting,” says Tina Tolson, senior director of operations for Johns Hopkins Medicine Language Access Services. Tolson created Juntos with Kathleen Page, associate professor of medicine; Centro SOL (Center for Salud/Health & Opportunities for Latinos) and the Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Health Equity.

The service does not replace medical interpretation, Tolson says, but offers additional support for this vulnerable population. “The Juntos providers are often able to ascertain more information directly from the patient to promote healing and ensure understanding of a complex clinical situation,” she says.

Talia Robledo-Gil, an internal medicine-urban health resident, is one of about a dozen Juntos volunteers who talk with patients and family members, sometimes answering questions and sometimes simply easing their isolation and fears. “With really critically ill patients, it can mean explaining to their loved ones why they need to be intubated, even though they seemed fine yesterday,” says Robledo-Gil, who grew up in a bilingual, bicultural Miami home with parents born in Peru.

· COVID-19 Testing and Follow-Up. Johns Hopkins clinicians are traveling to homeless shelters, sober living facilities and neighborhoods deemed COVID-19 hot spots to provide on-site testing.

They set up temporary testing sites, including one that was under the Jones Falls Expressway, in response to requests from the city or from organizations like Health Care for the Homeless or the Helping Up Mission.

The testing teams notify people of their test results and help them get appropriate care if needed.

One option as a place to live for people with mild or asymptomatic COVID-19 — and for health care workers — is the Lord Baltimore Hotel. Through a partnership among Johns Hopkins, the University of Maryland Medical System and CareFirst, the hotel is providing rooms to people who are homeless or living in crowded conditions that make physical distancing difficult.

· Food. Grab-and-go meals and food pantries are available for employees at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center and Sibley Memorial Hospital. Wilson notes that employees may be living in households with reduced incomes because of pandemic shutdowns, and they may have safety concerns about going to a grocery store. Johns Hopkins also works with the Maryland Food Bank to provide meals to thousands of low income adults in East Baltimore.

· Advocacy. “We are working with our government and community affairs team to brief state lawmakers about COVID and disparities,” says Golden. There are also plans to recommend legislation aimed at reducing health disparities, she says, but they are still in the early stage. “We are able to have our pulse on a lot of these issues because we are talking and listening to residents,” says Wilson.

The programs all build on the recognition that health care does not begin and end at the hospital door. Sometimes, it takes the form of a virtual lesson with teenagers.

Galiatsatos, previously a guest teacher at the Maree G. Farring Elementary/Middle School in Baltimore, returned recently to give lessons about COVID-19. He discussed the chemistry of sanitizers and explained the importance of masks. One student confided that her mother might have COVID-19, and Galiatsatos arranged testing and the care she needed.

“My school has a very diverse population of learners,” says Olivia Veira, a teacher at Maree G. Farring. “A lot of their information comes from memes and social media. They want to know where the virus came from, and when this will be over.

“Dr. Galiatsatos answers in terms that are accessible to students, while also emphasizing the importance of masks and physical distancing. He’s giving them real scientific information.”

Read more:

New Research Confirms Higher Rates of New Coronavirus in Latinx Populations

Johns Hopkins Medicine Leads Effort to Bring COVID-19 Testing to Hard-Hit Communities