When the weather is nice, you can find Margaret “Maggie” Freeman, certified ophthalmic assistant, on her front porch sketching, drawing or painting anything from abstract patterns to surreal art.

“I have been drawing ever since I can remember,” says Freeman. “I took art classes in school but did most of my drawing at home with my family.”

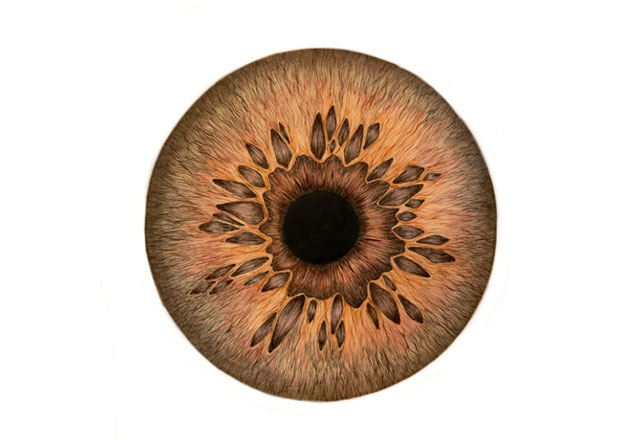

Both her parents are graphic designers, and her older sister, whom she credits as an artistic inspiration, is a fine artist. Although Maggie grew up drawing and appreciating art, ophthalmology has opened a new realm of art exploration and technique expansion that she had never thought of before becoming an ophthalmic technician. These days, she has her sights on a new muse: the iris.

“After looking at so many eyes through the slit lamp, I came to really appreciate the iris. The color and structure of the iris differs from one eye to another,” says Freeman. “There are a few general types of patterns that irises have that I noticed; some have ocean waves and others have lots of holes, in a flower-like pattern.”

In 2019, after completing the ophthalmic technician training program at Howard Community College, Freeman accepted a position with the float pool at Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins Medicine. A year later, she was working in the retina clinic, when she found herself riveted by a prosthetic eye display that featured information about the institute’s artificial eye clinic. That moment would change the trajectory of her career.

“I couldn’t stop looking at it. It was shiny, realistic and beautiful. The most amazing part to me was the red fibers used to create the look of blood vessels,” says Freeman of the artificial eye display. “I had an epiphany. Right then, I knew I wanted to make prosthetic eyes.”

She wanted to become an ocularist.

An ocularist is a medical specialist trained in designing, fitting and forming fabricated eyes. To become an ocularist, trainees can enroll in a comprehensive curriculum consisting of 750 credits from the American Society of Ocularists College of Ocularistry — a one-of-a-kind program in the United States. Alternatively, trainees can complete an apprenticeship with a board-certified ocularist for a minimum of 10,000 hours, or five years. According to the American Society of Ocularists, there are approximately 170 board-certified ocularists practicing in the United States, three of whom are in Maryland.

“It’s a combination of my love for science, art, eyes and helping people,” says Freeman.

Freeman had a conversation with her then supervisor, Mike Hartnett, ophthalmic clinical supervisor, about her plans to pursue an ocularist career. Hartnett says she was surprised and delighted when Freeman expressed her career aspirations, in part because no other technician had ever approached her to be an ocularist. Hartnett arranged for Freeman to shadow ocularist Tim Friel during his prosthetic eye clinic held each Monday in the Oculoplastics Division at Wilmer’s East Baltimore campus.

“Maggie is an accomplished artist who is fascinated by the beauty of the human eye,” says Hartnett. “Wilmer is able to support technicians through many ways. It was the right thing to do.”

Freeman observed Friel create an eye socket mold for a patient whose eye was recently removed, and she watched — in amazement — as Friel painted an iris onto a prosthetic eye in 20 minutes — real time, in front of the patient.

“I observed how Mr. Friel explained to the patient, in an informative, but sensitive manner, the process of getting an artificial eye,” recalls Freeman. “It was a wonderful introduction to the world of ocularists because I got to see him do a little bit of each part of his job. This showed me how much of a craft this type of work truly is.”

To continue her journey to becoming an ocularist, Freeman believed the best thing to do was to register for school. Last fall, she enrolled in Arizona State University’s online program to pursue a Bachelor of Arts degree in biology. She says taking courses online allows her to work part-time and to continue working on her craft, for which she says she is grateful to Wilmer.

“Wilmer has had a huge impact on my introduction to the field of ophthalmology and everything around it. It has helped me discover what I can accomplish,” says Freeman. “Who knows what the future of prosthetic eyes looks like with progressive, modern technology? I am looking forward to being part of it.”