It’s a rare calm morning in the psychiatric treatment services area of the adult emergency department of The Johns Hopkins Hospital. The locked 12-bed space is below capacity, with just six people dozing or quietly sitting on their beds. Unlike the day before, security guards don’t have to calm several agitated patients.

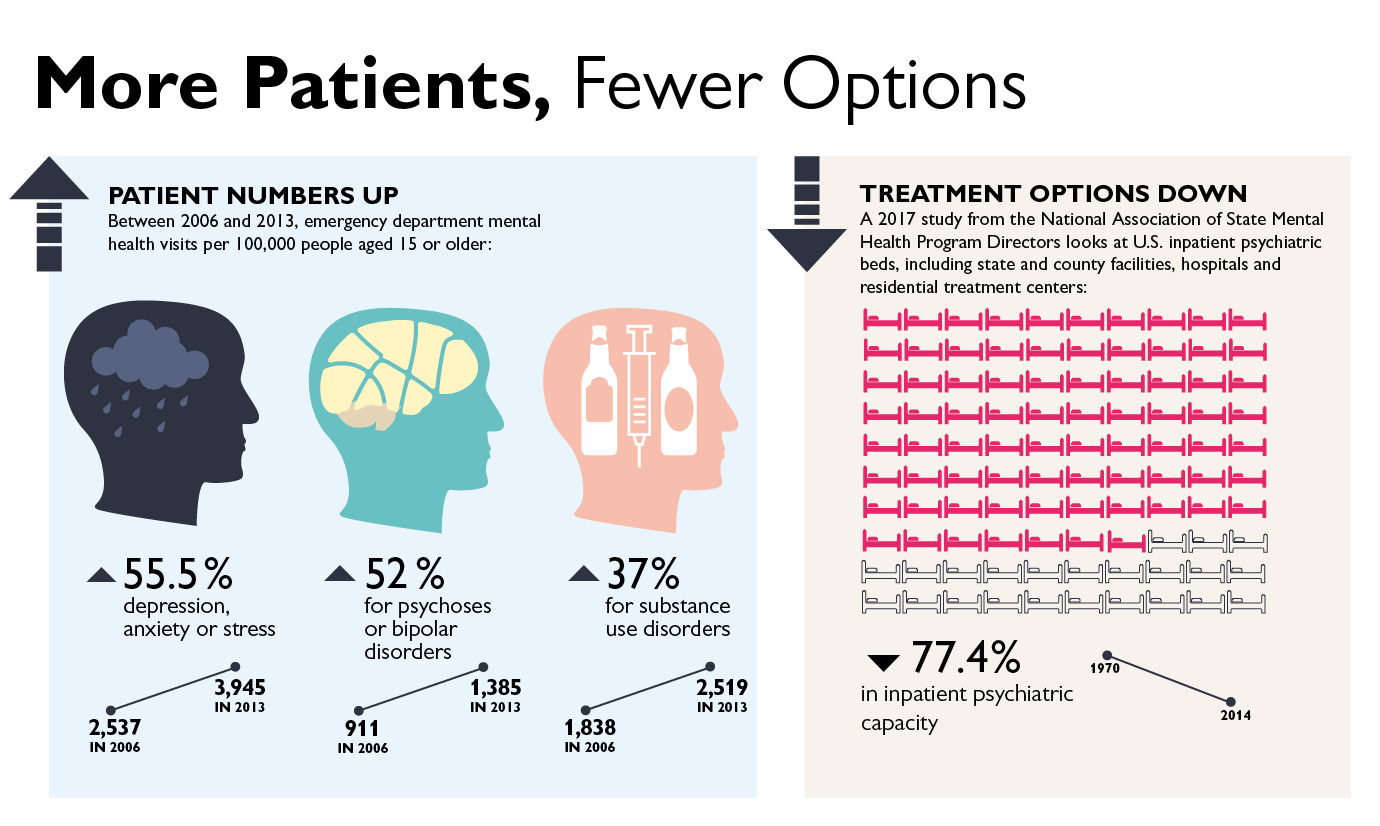

Nationwide, the number of patients needing emergency psychiatric care has been increasing, while inpatient treatment options have grown scarcer. Hospitals in the Johns Hopkins Health System are proactively coping with this new reality in order to provide the best care possible to this vulnerable population. They are building larger and better psychiatric areas in their emergency departments to ensure patient safety and comfort, adding features like televisions, hot meals and showers.

And they are staffing their psychiatric emergency areas with specially trained clinicians, who are adept at assessing psychiatric conditions and can often provide stabilizing medications.

One such specialist is psychiatric nurse practitioner Emma Mangano, who walks from bed to bed on that calm morning at The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

She strikes up conversations with each patient, assessing their moods and reassuring them that she’s working to find treatment options. Mangano radiates compassion and confidence, even when one patient steps uncomfortably close to her, clenching his fists by his sides.

“I can’t take it in here,” the patient says, near tears, as a security guard quietly moves closer. He doesn’t remember repeatedly punching the wall. He doesn’t understand why his mother called the police, making him the only involuntary admission that day.

“We’re really worried about you,” Mangano replies. “Your mom is worried about you.” She tells him he needs inpatient treatment, but no beds are available yet. “We’ll keep you posted and try to get you out of here soon.”

After Mangano walks away, the man waits a few minutes, then ambles a little too casually toward the bathroom before dashing toward the doors leading out of the unit. The doors are locked, though, giving the same security guard time to approach and gently pick him up, pressing the patient’s arms into his sides to lift him and carry him back to his bed.

More Psychiatric Patients

Mangano began rotating through the psychiatric unit of the Johns Hopkins Hospital emergency department when she became a nurse in 2007. She became a nurse practitioner in 2013 and left the hospital to work in a private practice, before returning in her current job in 2015.

In her years at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Mangano has seen a sharp increase in psychiatric patients coming through the emergency department — people who are suicidal, violent or too agitated or disconnected from reality to function. These include patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, autism, dementia, depression or substance use disorder.

According to Vinay Parekh, attending physician for psychiatric emergency services at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, the volume of behavioral health patients at the hospital has increased more than 60 percent since 2012, to about 400 patients a month.

Emergency medicine is a relatively new specialty, dating to the 1960s and becoming official in 1979. From its start, patients with psychiatric conditions turned to their local emergency rooms for help, and the numbers increased as treatment options such as inpatient psychiatry care and addiction counseling dwindled.

Reasons for the rise in psychiatric emergency visits, both locally and nationally, include the opioid epidemic, which has increased the number of people struggling with substance use disorder; the Affordable Care Act, which has given more Americans insurance that covers mental health treatment; and growing public awareness about mental illness, which makes people more likely to seek treatment for themselves and to take seriously threats of suicide or violence from others.

Johns Hopkins Responds

To meet demand, Johns Hopkins hospitals have added, expanded and improved psychiatry units within emergency departments.

The Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center expanded its psychiatric emergency unit from six beds to 10 in 2017, when the hospital opened its new emergency building. Suburban Hospital opened a new emergency psychiatric unit in April, expanding capacity from two beds to six and creating a safer and more therapeutic setting for patients. Howard County General Hospital expanded its adult psychiatric emergency area from six spaces to eight in May, and added a five-bed space for pediatric psychiatric emergency patients.

When Mangano joined The Johns Hopkins Hospital in 2007, the psychiatric emergency department was just a designated hallway in the main emergency room. A separate and locked psychiatry emergency space opened a couple years later, and was expanded from four beds to eight in 2012 when the hospital opened new adult and pediatric emergency departments. It was reconfigured the following year to make room for 12 patients.

Yet overcrowding continues. In January 2018 alone, the psychiatric emergency unit at The Johns Hopkins Hospital was above capacity more than half the time. When that happens, behavioral health patients get care in the regular emergency room.

While the new and expanded units are not identical, they have similarities. All the psychiatric emergency departments are separated by locked doors from the rest of the emergency departments and staffed with clinicians and security guards who specialize in caring for this population.

“We develop relationships with the patients,” says Mangano. “When they come in, the nurses do a complete psychiatric history. They’ll write a note that, in just a few sentences, often gives great insights on the patient. We make recommendations to the doctors.”

Like other hospital employees, psychiatric emergency staff learn de-escalation techniques aimed at defusing potentially tense or violent situations, including specific skills such as how to listen without being condescending or dismissive, and how to restrain patients gently, to reduce agitation.

Patients come to the psychiatric emergency areas — sometimes voluntarily, sometimes escorted by police, family or friends — through the regular hospital emergency rooms. Security guards search arriving patients and temporarily store potentially dangerous items such as shoelaces, belts or jewelry.

In the psychiatric units, wires and sharp medical instruments are out of reach. There are no framed posters on the walls. The mirrors are shatterproof.

Connecting Patients with Care

As with all emergency departments, the purpose of the psychiatric emergency units at Johns Hopkins hospitals is to stabilize patients, and find long-term treatment.

Psychiatric emergency patients stay longer than other emergency patients because placement is challenging. Inpatient psychiatric beds and outpatient services such as addiction treatment or counseling are scarce and often expensive.

In Maryland, the number of state-operated psychiatric beds dropped from 4,390 in 1982 to less than a thousand today, according to the Maryland Health Care Commission.

“We try to get people out as quickly as we can, but there’s a shortage of beds,” says Susan Webb, director of behavioral health emergency and outpatient services at Suburban Hospital. “People might stay for days or weeks. We had one man with dementia recently who was here for two months before moving to a memory care facility.”

At The Johns Hopkins Hospital, the increasingly difficult job of finding psychiatry beds belongs to Katherine Pontone, nursing coordinator for the department of psychiatry. About 40 percent of the psychiatric emergency patients at The Johns Hopkins Hospital get admitted to the hospital, she says.

The hospital has 83 inpatient adult psychiatric beds. Designations include general psychiatry; geriatric psychiatry; schizophrenia care; dual diagnosis, for people with substance use disorder and another mental illness; chronic pain; eating disorder treatment; and treatment for people with mood disorders such as major depression or bipolar disorder.

Pontone does her best to match patients to the appropriate bed. But options are limited, and patients sometimes have to wait days in the emergency department.

The Johns Hopkins Hospital recently began serving three hot meals a day to behavioral health patients in the emergency department. They can also be escorted to a shower in the hospital and started on new medications under some circumstances, says Parekh, attending physician for psychiatric emergency services at the hospital.

Sometimes, while they’re waiting to leave the emergency room for an inpatient bed, they are able to get enough care or medication stabilization that they can be released to a lower level of outpatient care, Parekh says.

Patients who are released might leave the psychiatric emergency unit with referrals for outpatient addiction treatment or counseling. But appointments are often hard for patients to get or to keep.

Howard County General Hospital has begun Rapid Access programs for both children and adults, which ensure that psychiatric patients leave the emergency department, even on weekends, with appointments for outpatient treatment, not just referrals.

The Johns Hopkins Hospital is also helping patients receive treatment without turning to the emergency department. The hospital’s Assertive Community Treatment Teams consist of case managers, nurses, therapists and psychiatrists who meet patients in their homes or at designated locations to check on them and provide care, including medication management.

On that calm morning at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, at least one patient is relying on the psychiatric emergency department for her medication management. She’s a woman with bipolar disorder and a history of violence, who seeks help regularly when she’s in danger of harming others.

To pass the time, she shows Mangano a photo of a smiling granddaughter. “She’s getting so big,” coos Mangano, who has charted the girl’s growth over years.