Jeffrey Kahn, director of the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute for Bioethics, is an expert on the ethics of genetic modification.

As the only bioethics professor serving on a prestigious new panel, the International Commission on the Clinical Use of Human Germline Genome Editing, Kahn is helping shape standards for the potential use of germline genome editing in humans, a type of genetic modification that passes the changes on to future generations.

The issue took on new urgency after Chinese scientist He Jiankui announced in November 2018 that twin girls had been born using embryos he had modified so they would be more resistant to HIV.

Responding to widespread outrage and concern, the United States and United Kingdom, in partnership with the science societies from 32 other countries, formed the commission of scientists, lawyers and leaders in health care and health policy. Its first meeting was in August, in Washington, D.C.

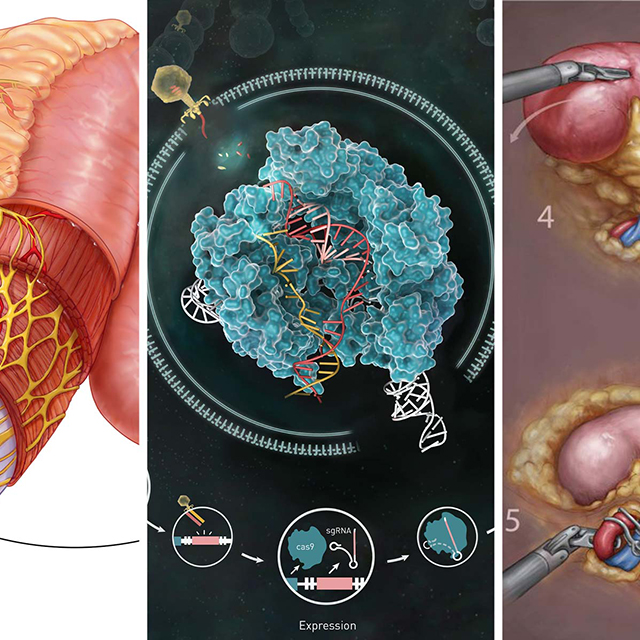

Genetic modification, possible since the 1970s, has been used to make food more nutritious, create synthetic insulin and provide promising treatments for illnesses including leukemia and sickle cell disease. CRISPR, a gene-editing tool introduced in 2012 and used at Johns Hopkins since 2014, has removed many of the technical and financial barriers to this progress.

But the relative costs and benefits of germline editing are not yet known.

This is not Kahn’s first time developing guidelines for germline editing. He was also a member of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine committee that issued a 2017 report that outlined principles for the acceptable uses of gene editing in humans.

The report said germline modifications might someday be allowed, but only to cure or prevent deadly diseases, and only if there are no other options. (See box.)

The Chinese researcher, however, didn’t follow those guidelines. He altered the CCR5 gene in the embryos to mimic genes in people with a mutation that makes them more resistant to HIV — a disease with other options for both treatment and prevention.

“I thought our report was clear about what criteria need to be met,” says Kahn. “Dr. He said he followed those rules, but the global reaction indicates that he clearly did not.”

He’s research has been suspended, and he is rarely seen in public. It’s unclear if he will be punished further.

Dome asked Kahn about the ethical implications of He’s experiment, and the future of germline editing.

Q: You were at the 2018 International Summit on Human Genome Editing in Hong Kong when He announced that the genetically modified twins had been born. What was the reaction?

The meeting was very dramatic. Instead of a formal announcement, the information came out via news reports and YouTube videos, timed so that the news would be released to the public when scientists and media would be together at the conference. The media just swarmed anyone with a speaker badge for their reactions, including me.

I was not terribly surprised that somebody would do it because CRISPR and other gene-editing tools are easier to use than previous gene-modifying technologies. I was surprised at the timing and that it was someone who was part of the community of researchers, working in an academic setting. I would describe Dr. He as a rogue, but not a charlatan. He knew what he was doing.

Q: What are your concerns, as an ethicist, about using gene editing to create babies with less risk of becoming HIV positive? Isn’t that a good thing?

It’s much too early to say this is an unmitigated good or anything approaching that. There is so much we still don’t know.

One criterion outlined in the 2017 National Academies report is that it should be considered only to cure or prevent deadly diseases, and only if there is no alternative. Modifying genes to make someone more resistant to HIV does not meet this standard because it is not a cure and because HIV can now be managed as a chronic disease. The father of the twins was said to be HIV positive, but there are ways to prevent HIV infection during in vitro fertilization that don’t require genome editing.

The report also recommended that there be extensive preclinical research on animals to understand the unintended consequences of germline editing. Another is that the information must be shared widely and transparently.

As far as we know, He did not do any of those things. We don’t know how many embryos were modified, how many women became pregnant and how many resulted in babies. And did the intervention actually succeed in reducing HIV risk? And more importantly, at what costs to the children’s health? There is evidence that altering CCR5 genes could lead to impairments, including cognitive delay.

In addition, the consent process with the parents, from what we can tell, did not meet accepted international standards. It more or less said he was offering a “vaccine” against HIV via this technique. It didn’t say anything about genome editing. It didn’t say it had never been done before in humans. It didn’t say there are other ways to avoid having an HIV-infected child. The women received free in vitro fertilization as a result, a powerful incentive to participate in the study.

Q: Gene editing is hailed as an important way to fight horrific diseases. Why is there so much concern about this particular case?

A: I think the main reason is the reproductive context.

If He had gone “by the book,” there would have been years of research with animals and nonreproductive somatic cells first, and many opportunities to pause and discuss the results of the research along the way. It could have taken 10 years or more to get to the point of editing genes in eggs, sperm and early-stage human embryos, leading to the germline changes we’re discussing.

All that said, my guess is that it will be hard for the world to prevent the use of gene editing technologies in ways that create heritable genetic changes, and not only to prevent diseases but to introduce enhancements.

Q: Does Johns Hopkins have any formal policy about how to work on projects that involve gene editing?

A: The use of gene editing in humans is regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health. We follow federal rules, and Johns Hopkins guidelines can be found here.

Q: There have been questions about whether He’s work should be published in a peer-reviewed journal, since it does not meet accepted research standards. Where do you stand on that?

A: His work has not been published, partly because it hasn’t been submitted. But there is a broader question that isn’t new about how to use data that were obtained unethically.

My view is we should ask the people who are affected, and they should get to decide, when possible. In this case, we don’t actually know for certain that these twins exist and if they have edited genomes, but if they do, they are minors.

At a minimum, if there is a decision to publish there should be some kind of flag or boxed statement, in bold and at the top of the article, stating the failure to follow accepted ethical standards. That way, every time someone reads or cites it, the provenance of the research findings will be clear.

Q: You are a member of the International Commission on the Clinical Use of Human Germline Genome Editing, which had its first meeting in August. How is that going?

A: We’ve had only one meeting, and I’m not supposed to opine on our work so far. But one of the obvious answers is there needs to be greater specificity and clarity than what was in the 2017 report — that much was announced at the public session that kicked off the meeting.

Presumably, there will be recommendations regarding regulation and oversight, but those details are what we’ll work on in the coming months.