Patient Story

Epilepsy: Ryan's Story

Patient Story Highlights

- At age 3, Ryan’s right leg began to shake, but, by age 10, the shaking led to a minute-long seizure in his right side.

- The seizures continued and worsened, eventually sending him to the Emergency Department at the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center.

- At Johns Hopkins Children's Center, pediatric neurologists began searching for the lesion triggering the seizures.

Ryan Bigelow’s parents were concerned when at age 3, his right leg began to shake a bit for a day or two. What Ryan jokingly called his “wiggly leg” showed up again a month later, a pattern that would repeat itself over Ryan’s early years. Then, at age 10, Ryan’s wiggly leg spread to his entire right side in a violent, minute-long seizure. The Pasadena, Maryland, family called 911.

“He was given Ativan at the emergency room to ‘break the episode,’ a term we would become very familiar with over the next five years,” says Ryan’s dad, Sonny Bigelow.

Ryan was diagnosed with epilepsy—the idiopathic form, in which the cause is not known. Like many children with epilepsy, he would be managed with anti-seizure medicines that reduced the frequency and severity of his partial seizures but did not eliminate them. For Ryan’s parents, life became a continuous cycle of adjusting and changing medications, giving him multiple drug cocktails. However, no matter what combination doctors tried, Ryan’s seizures continued to get worse—confining him to a wheelchair because even the slightest pressure on his right foot would trigger seizures. The parents were distraught, Ryan in despair.

“I remember telling him when he was 10, as tears started rolling down his cheeks, that it’s OK to cry,” says Sonny. “Then, he said, ‘I hope this is not a lifelong condition.’”

That, however, appeared to be the prognosis. Indeed, at what Sonny calls Ryan’s “first and last day at high school,” he collapsed from another violent seizure that paralyzed his right leg and sent him to the Emergency Department at the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center. But that visit turned out to be serendipitous, as physicians noted that Ryan was not presenting as a patient would with idiopathic epilepsy. He was no longer having “episodes” of seizures but continuous seizures—60 or more a day—a condition called epilepsia partialis continua. The good news was Ryan’s epilepsy was reclassified as refractory epilepsy, or drug-resistant epilepsy, which meant that it could be treated surgically—but only if a lesion in Ryan’s brain triggering the seizures could be located. As it turned out, that would be no easy feat.

For the next six days, under the direction of pediatric neurologist Sarah Kelley, who has extensive experience treating children with refractory epilepsy, Ryan’s seizures were captured by EEG and video in the epilepsy monitoring unit. But while the EEG suggested a possible area of abnormality in the brain, the MRI scans did not reveal anything structurally wrong in Ryan’s brain. The culprit lesion was still in hiding, and Kelley felt it might take a needle-in-the-haystack search to find it.

Enter pediatric neuroradiologist Bruno Soares, who was asked to review an earlier MRI scan of Ryan that had been interpreted as normal. Correlating Ryan’s clinical picture and EEG, he knew almost immediately where to look for the lesion on the scan.

“I went to the patient’s chart and saw that the seizures start in the right hip and leg, so it’s something in the motor area of the brain on the left side,” says Soares. “And the spikes in the EEG suggest the seizure focus is near the vertex, the top of the brain, in the primary motor cortex that controls movement.”

From there, Soares scanned the convolutions and folds in the cortex, where there should be a clear demarcation between gray and white matter. There, at the bottom of a sulci, an enfolding in the brain, was “a little bit of blurring between the junction of gray and white matter,” says Soares, what he knew was a shadowy sign of a certain type of lesion. In his mind, the search for the source of Ryan’s seizures was over.

“I said it’s very subtle, but this patient definitely has a focal cortical dysplasia,” says Soares, noting that the literature shows up to 40 percent of these very faint lesions can be missed on conventional MRI scans. “Now, suddenly everyone in the epilepsy conference is excited and hopeful because there is a lesion, something to address.”

Doing the addressing would be pediatric neurosurgeon Shenandoah “Dody” Robinson. But first, both she and Kelley wanted additional imaging to confirm that this lesion was indeed the culprit. To determine the extent of the lesion, they ordered a magnetoencephalography and a higher-magnification MRI scan using neighboring Kennedy Krieger Institute’s 7 Tesla research MRI scanner, which produces higher-resolution images than those generated by the 3 Tesla MRI scanner used by most academic medical centers. Ryan would become the first patient under a new clinical protocol using the 7 Tesla, which depicted the lesion in greater detail.

“It looked like a teardrop of cells at the bottom of a sulcus folding in the cortex of the brain, very close to the left motor strip, the area that controls the movement of the right side of the body,” says Kennedy Krieger pediatric neurologist Michael Johnston.

Now the team, knowing that removal of a focal cortical dysplasia can result in a seizure-free outcome, was really excited. But knowing where the lesion lived did not mean removing it would be risk-free, as the lesion was a few millimeters away from the area in the brain responsible for language and motor movement. Ryan was at risk of losing the function of his right arm and leg, as well as his speech.

Intracranial monitoring in the epilepsy monitoring unit helped reduce that risk, and subcortical motor brain mapping was used during the operation to ensure vulnerable areas were not injured. With advanced neuro navigation at her side, Robinson was able to remove the lesion last November.

The patient’s outcome?

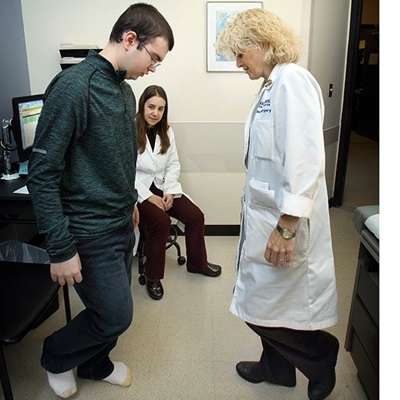

Immediately after surgery, Ryan was able to speak, and 24 hours later, he gave his family a high-five with his right arm. Two weeks later, Ryan was walking with a slight case of drop foot, which with physical therapy was improving.

“I do not know how Dr. Robinson was able to successfully perform this difficult and delicate surgery so close to these motor control areas without any noticeable impairment—it’s a miracle,” says Sonny. “There are no words to describe how wonderful Dr. Kelley and Dr. Robinson are, or how wonderful the epilepsy monitoring unit, the surgical team, the PICU staff, the pediatrics ward staff and the physical therapists at the Kennedy Krieger Institute are. I can only tell you that the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center pulled out every stop to make sure that Ryan received the best care possible.”

Kelley adds: “We received an email from the family over Christmas saying Ryan’s wheelchair is collecting dust in a corner. He’s walking everywhere, and the family is very happy we gave them their son back. They said it’s the best Christmas present they could ever have.”

For the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center and the Kennedy Krieger Institute, this case was the catalyst for the shared evaluation and treatment of patients like Ryan, as well as those with cerebral palsy and neurodevelopmental disorders.

“Historically, we’ve drawn more severe patients who may be eligible for a surgical approach, but because of the number of problems they have, surgery has not always been accessible to them,” says Johnston. “With Dr. Robinson, there’s a real collaboration in seeing these patients.”

For referrals to the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center, call 443-997-5437.